The persistent economic theme of 2014 was that it was better than 2013 or 2012. Therefore, it was assumed, that meant everything had been set right and the temporary disturbances of those prior years were put to the past. It was a fundamental error not just of conflating relative versus actual, but completely ignoring how it was something we had never seen before. As noted earlier with factory orders, whenever the economy had been knocked down prior to the Great “Recession” it had always, always responded with vigor. In 2014, despite QE3 and QE4 supposedly at its back, the economy was but listless, just a little less than it had been in the months more directly contacted by what really mattered (“dollars” in 2011 and the aftereffects).

I wrote at the time, in September 2014, that what really mattered was not that a weak economy wasn’t right then getting weaker but that it obviously wasn’t getting stronger (unemployment rate aside, because it wasn’t being corroborated). As far as income and consumer spending, this was a big deal:

Even the revised spending figures (shown above) are “better” in terms of 2014 vs. 2013, but so what? Going from really bad to mostly really bad is not an achievement of any kind, and it suggests more about the lack of actual growth than a solid foundation for reaching “next year.”

This is a unique period in economic history, where the level of upward attainment has been so lacking; stuck at the bottom as it were.

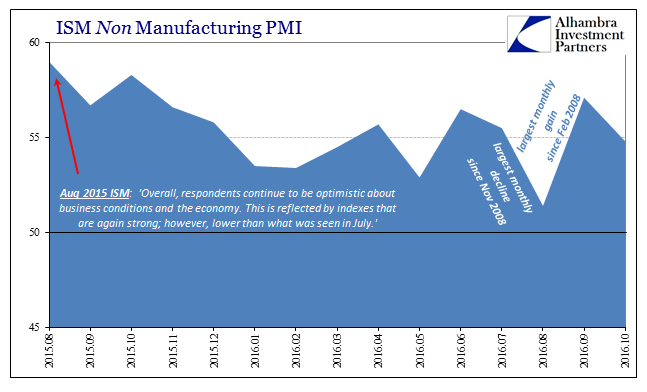

What the “rising dollar” showed was that there was another lower bottom yet to be discovered. The difference this time is that more parts of the economy have been captured, and of those that were similarly effected in 2012 they have been again in a much bigger way. One of these elements was the services economy. The ISM Non-Manufacturing PMI slid back to 54.8 in the latest release for October 2016, after being up sharply in September at 57.1 – which followed being down sharply to 51.4 in August. In other words, the same volatility as we find in other PMI’s that suggest, strongly, this weakened economy has now ensnared the services economy in the same weak but not weaker pattern.

What I was suggesting in 2014 (and before) was that though this condition was imperceptible it was only because there was confusion about what relative changes meant; where improvement that year was still unlike actual improvement, pointing to great difficulty defining such terms so that they would be both appropriate as well as consistent with reality.

Does it matter if current levels of spending have moved from pretty recessionary to just recessionary? The fact that growth remains stuck here again suggests not just the absence of recovery and the low probability of it actually showing up, but rather a very strong and dangerous structural issue that relates to elongated “cycles” without any significant peaks.

What truly mattered for understanding what was going on, and more so the risks of what was about to happen, completely unappreciated by the changes in the unemployment rate, was not that some of the numbers were more positive but that they were more positive in a way that was distinctly different than all prior historical experience. That had to be a strong consideration for any reasonable analysis; it demanded to be factored, yet it was ignored because economists wanted QE to work and therefore considered only what they wanted those numbers to mean. Again, the economy of 2014 was not recovering, it was merely waiting out the time between monetary disturbances. And already at that moment, the “next one” had already been unleashed.

People are making the same mistakes all over again for the very same reasons. It is absolutely true that history repeats because no one was listening the first time. In 2014, the services economy seemed fine, perhaps even more than fine. By 2016, it isn’t recession in services, but whatever this is (depression is a word that too often scares people out of objectively considering it) has added that sector to the catalog of variable downward pressures. Like then, what matters is not that ISM PMI is up occasionally, rather that it isn’t actually progressing forcefully and consistently.

What we saw to start this year was not the happy result of avoiding recession, rather it was the alarming inevitability for this misunderstood economy that had decayed so severely as to widen its encirclement of what counts in that condition. The lack of actual recovery then was a big problem to consider given what had been started earlier that summer. From August 2014:

That is what all this [bonds and eurodollars] amounts to, a reversal, maybe just its initiation right now, of the paradigm that kept favorability running for almost three years. Central banks at the end of 2011 and into 2012 promised all sorts of means by which to create the mythical recovery, which would have cured so many, if not all, nagging problems and imbalances left over from the Great Recession and panic. “Markets” gave central banks the benefit of the doubt about those promises and reacted and priced as if they were to come true.

Two years later, it still hasn’t come true as the economy remains now as it was then; just in yet a lower state.

Stay In Touch