Joe Calhoun recently noticed a bit of a structural shift taking place in the repo market, and he was right to point out the Fed’s role in the process. QE 3 has caused some of the usual “unforeseen” and unintended consequences that ripple through wholesale money markets. I have been highlighting a related drop in swap spreads, particularly the 10 & 7 year maturities. These events, in my opinion, are related (as you will see below).

For the mainstream media, there is always an urge to simplify some of the more complex elements to modern monetary finance. That is certainly understandable since a lot of this wholesale money system (the banking system does not run on deposits and money multipliers anymore) is foreign and even somewhat unnatural and counterintuitive. But for all of modern banking, repos are the key to moving money about. When the Fed speaks of liquidity, they mean repo markets more than anything because the modern banking system runs on collateralized loans – especially in overnight and short terms.

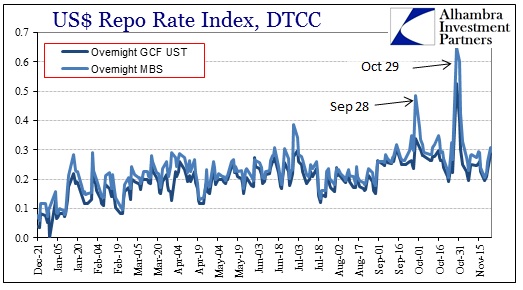

For most of 2012, the GCF repo rate (the indicated interest cost on general collateral) has been moving higher.

Not only have repo rates struck an upward trend, there were noticeable spikes at quarter end (which is typical) and at the end of October. While temporary dealer positioning accounts for these, the fact that they were not fully unwound (and had been rising into quarter end) through October and November points to a potential change in the wholesale market for collateralized lending.

As with any market, there are both supply and demand considerations. For repos, however, that supply/demand dynamic is not limited to available cash lenders, it also holds for the usable collateral. So while rising interest rates in other cash markets might look like growing illiquidity, there is another side to the repo market that may offer a more complete explanation.

For example, while the Federal Reserve explicitly meant QE 2 as an enhancement to bank liquidity, the operational aspect of purchasing US treasuries from the marketplace had the exact opposite effect. The Fed was trading newly created reserves for usable collateral in high demand. After 2008, unsecured lending even at overnight terms had all but ceased to exist – making LIBOR nothing more than a fantasy interest rate. Without an open monetary channel in unsecured lending, those newly created reserves were worthless without a means to circulate them. But QE 2 was actively reducing the available supply of collateral, meaning that liquidity was getting worse, not better.

This demand for collateral was reflected in t-bill rates, which fell often below zero and which the media mistakenly identified with a “demand for safety”. It was not really safety driving rates to zero, it was demand for liquidity growing into an artificially diminishing supply. Furthermore, a lot of that demand for US$ repo was coming from Europe. So QE 2 had the wondrous effect of heightening the growing European banking dysfunction at a particularly inopportune moment in 2011.

We can see clearly that collateral supply is not creating similarly illiquid conditions in 2012. Beginning with Operation Twist in September 2011, the Fed has been actively supplying short-dated US treasuries to the repo market (and buying up to the SOMA limit in longer-dated securities). So the “oversupply” of t-bill collateral has caught the attention of some mainstream observers as the culprit for rising repo rates, at least in that 2012 is in many ways the converse of 2011. This does make some sense in that a rising supply of US treasury collateral competing for cash lenders would tend to push rates higher.

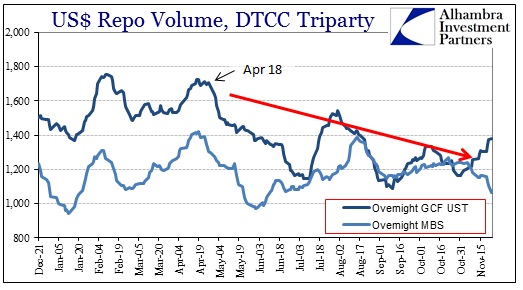

I find that explanation lacking, however. This is particularly true when looking at the supply of funds, or the volume, in the repo markets themselves. Since April 2012, US treasury repo volume has fallen off rather noticeably, while MBS volume has been relatively steady. If there was a rising supply imbalancing cash availability we would expect volumes to move in concert to that availability, matching the move in repo rates.

Instead, there are more mechanical issues that may be at work here. The commonly cited repo rate is the general collateral financing rate (GCF) that denotes what any linked dealer institution may pledge as “generic” collateral for an overnight repo. In addition to the general rate, there is something called the special rate.

First, to understand what specials are requires a bit of background. Repos are conducted using only the most liquid securities. The reason for this is obvious – in a collateralized loan, the security used as collateral needs to be liquid since the cash owner may need to sell it quickly to regain cash lent out in the case of default on that loan. Repo trades are simply collateralized loans. While US treasury securities are the most liquid credit assets in the world, they are nowhere liquid enough to satisfy repo counterparties. But one segment of US treasury markets do carry enough liquidity to make them repo-ready – on-the-run bills and bonds.

A treasury security that is just auctioned from the US Treasury Department is “on-the-run”. That is, from the time that bill is auctioned until the time another auction of the same maturity takes place it will be on-the-run, and thus will be highly traded and liquid. Once bonds and bills go “off-the-run” their liquidity dries up exponentially. So repo availability takes place with on-the-runs.

What makes the on-the-run market liquid is the demand for dealers to hedge their credit books and credit positions. That often means not just demand for their long positions, but often a demand for shorting treasury positions. With a heavy dealer presence on both sides of potential trades, credit market hedgers both inside and outside of dealers takes place in the on-the-run space. Like repos, a credit short needs to be liquid or the potential risk of loss becomes too great to bear. In this way, the repo market and the hedging market become very complimentary.

A short position in a US treasury requires a hedger (or speculator) to borrow a security for immediate sale, with the intent on buying it back at some point in the future at a hope-for reduced price. But a short position often needs to be closed with the specific security that was borrowed, not just a generic treasury. If there is a particular on-the-run issue with a heavy short position, that will eventually create higher demand for that particular security at some point in the future. This short-driven demand shows up in the repo market as a below-market interest rate. Those shorts will have to compete with each other to obtain the shorted bill to close out their positions – so they will accept a reduced return on cash in the repo market in order to obtain that specific issue or CUSIP. Whenever a specific repo security features a repo rate below the GCF rate it is said to be on “special”.

In a crude way, the amount or volume of “specials” in the repo market tells us something about the willingness of credit market dealers and speculators to short US treasuries. An elevated volume or number of special repo securities would indicate that there are a lot of short positions in the liquid markets. Conversely, a dearth of specials might indicate a lack of short US treasury positions.

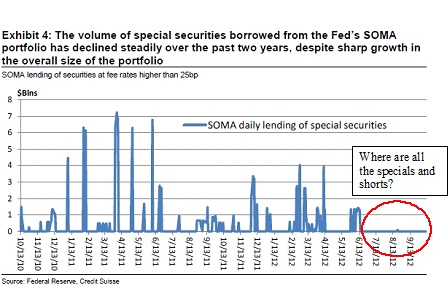

Since June 2012, as rumors and expectations of QE 3 grew and heightened, there have been very few specials, at least in those securities borrowed from the Fed’s SOMA holdings. According to Credit Suisse, that has been a dramatic change from 2011 and earlier.

This confirms the timing involved in rising repo rates where most of the increase has occurred after June. Whenever there is an increase in specials, the overall pool of general collateral declines as specials are “removed” from the general pool. As such, a smaller general pool would mean fewer available general collateral securities for a given cash demand environment, leading to falling repo rates (more cash chasing fewer securities). The converse would also be true, as we have seen since July. Fewer specials means a larger general collateral pool, and thus rising general repo rates.

Rather than cast a shadow of illiquidity over the wholesale markets, I think the lack of specials and the rising GCF rate points to the same thing we have seen in the swaps market. Fewer specials mean, in general, fewer short positions, which we can interpret as market participant (particularly dealers) expectations for lower interest rates – or at least extending the horizon for ZIRP still further. That is exactly how I interpret the declining and even negative swap spreads we have seen of late. Falling swap spreads indicate, among other things, an imbalance of counterparties seeking to pay floating and receive fixed, and thus an imbalance of those that expect any future increase in interest rates to move further out in time.

The timing for both of these moves is more than coincidental.

What this points to is, as I said, wholesale money and derivatives markets preparing for “unending” ZIRP. Unending may be too strong of an interpretation at this point, but we have seen this movie before. The Fed had originally intended, in the fall of 2008, to be removing its policies by this year (at the latest, we were told). Every year that “E-day” for instituting monetary exit measures gets moved further and further into the future as the mysterious “headwinds” apparently require more and more monetary “stimulation” (that clearly lacks potency). Where dealers and speculators once shorted US treasuries in anticipation of these exit policies, they no longer bother.

Indirectly, these positions count not only against expectations of rising interest rates, they are a commentary on the real economy. Expectations for a real recovery in the real economy would lead to expectations for rising interest rates (particularly now that Bernanke has pegged monetary interventions directly to the real economy) and would lead to more shorting in the treasury market and rising swap spreads; instead we see the exact opposite. These are big money players in the largest, most liquid markets positioning in exactly the same manner. These positions in these massive, extremely vital markets are a warning sign that the US banking system just may be following the Japanese path.

I have said on numerous occasions that ZIRP is like a roach motel; the economy checks in but it never checks out. Credit and money markets are catching on.

Stay In Touch