A few weeks ago the Federal Reserve announced its tentative plans to aid in exiting from QE’s balance sheet expansions. A new tool, that will not require additional statutory approvals or authority, called the “fixed-rate, full-allotment overnight reverse repurchase agreement facility” theoretically creates a new “risk-free” alternative to idle bank reserves. In the context of an exit from “emergency” measures, that seems like a necessary component.

There are several reasons the Fed would want to engage in this kind of activity, but none really apply most directly to a monetary policy exit. To see why, we need to start by revisiting (again) 2008.

From the outside, the wholesale money system seems monolithic. However, there is no interbank market; there are several varied interbank markets. Monetary policy in the modern system, particularly in the interest rate targeting regime that developed sometime in the 1980’s (we don’t know exactly when), has relied on open market operations in only the federal funds market. From there, monetary intentions were transmitted via primary dealers and OTC bank transactions. That meant that global dollar markets, particularly eurodollars, had no direct pipeline to the Federal Reserve, relying instead on the big Wall Street and London banks (with US primary dealer subsidiaries) to bridge that geographical/system divide.

In addition, the unsecured federal funds and eurdollar markets were augmented (and now replaced) by secured funding markets we call repos (repurchase agreement refers to the accounting/legal rules that govern repo arrangements, but a repurchase agreement is nothing more than a loan collateralized by some financial security). The repo markets are also scattered far more than unsecured lending markets, largely conducted in OTC bespoke transactions that are never registered on any centralized system or database. There is also a geographical divide to consider, as eurodollar participants may have operational constraints in moving from unsecured eurodollar funding to eurodollar repo.

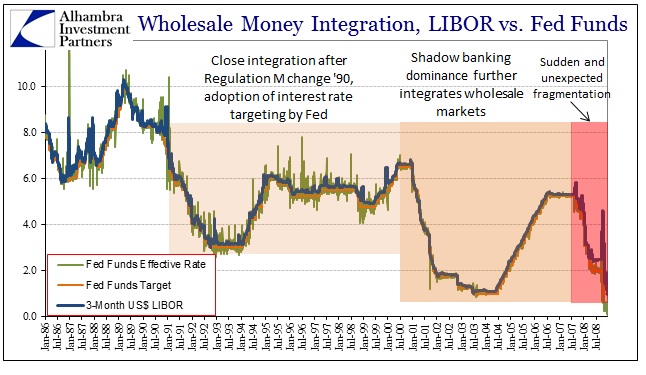

This fragmentation was never apparent before 2008. In fact, there was a demonstrable and empirical foundation for believing in durable integration of these money markets.

Monetary policy conducted through federal funds had a direct and proportional impact on eurodollars, denoted by the extremely close relationship between the effective federal funds rate, the target and LIBOR (the eurodollar rate). Any disruption of this tight relationship would be closed quickly via arbitrage trading at the global mega banks – if LIBOR rose to a premium above effective federal funds, a Wall Street bank (with a London sub) or a London mega bank (with a NYC primary dealer sub) could borrow the cheaper federal funds and offer them in London eurodollars to capture the spread. Since this was a relatively easy arbitrage, LIBOR and federal funds rarely strayed from each other giving off the outward appearance of durable integration.

After Bear Stearns failed in March 2008, however, there emerged a small but sustained premium in LIBOR over federal funds. This meant that banks were not taking advantage of the arbitrage opportunity to lend into London. This eurodollar premium was the first outward appearance of fragmentation that would grow far worse as the crisis progressed (and the Fed underestimated it at every step).

By the week Lehman Brothers failed, eurodollars became increasingly scarce, driving LIBOR rates much higher. Initially, the effective federal funds rate followed, but then gyrated massively before settling significantly below target. That denoted a desperate shortage of dollars in London, but a surplus of them in New York.

There are many reasons for the surplus in federal funds during the crisis, including the retreat of US money market funds from European counterparties (in unsecured and repos), preferring the statutory cover of the federal funds market where at least the Federal Reserve had direct input. But there were also complications in these markets because of the existence of non-banks, including the GSE’s, investment banks (Merrill Lynch, Goldman Sachs) and finance companies (like GE Capital).

As these wholesale money systems became more and more disjointed it spilled over into dollar repos. Unable to obtain dollar liquidity, European and global banks desperately searched for usable collateral (MBS collateral had been repudiated) to engage repos, leading to negative rates on US t-bills (and the collapse of rehypothecation chains as collateral was valued more than “reserves” of dollars).

From the perspective of the Federal Reserve, there were a myriad of problems that went way beyond operational structure. The Fed had the Discount Window, but it wasn’t available to non-depository banks and nobody wanted to use it since it carried not just a stigma but the seal of bankruptcy and insolvency. In terms of repo markets, the Fed tried some smaller measures (more below) but was really ill-equipped to intervene. As far as eurodollars, the Fed engaged in dollar swap lines with other central banks to indirectly inject dollars into the global system to alleviate the global dollar shortage.

At the height of the panic in 2008, the Fed was engaging in exactly these kinds of reverse repos, “draining” reserves from the system contrary to conventional wisdom about monetary affairs in that period. I wrote back in May a summary of these “anti-reserve” policies,

“A reverse repo program, then, accomplishes two goals simultaneously. First, by removing reserves the central bank can help alleviate the surplus in the Fed funds market and attempt to push the rate back up toward the target. There is nothing so loathsome to a central banker as an interest rate that does not conform to its target, whether above or below. It is a highly visible signal to money markets and financial participants that something is very awry.

“Second, the reverse repo, while draining reserves, actually injects the dealer system with desperately short collateral. Since the Fed is taking in cash and moving out government bonds, it places the Fed in the role of collateral distribution rather than the more traditional money supply expansion.

“In addition to these measures, on September 17, 2008, the Federal Reserve formally requested assistance from the US Treasury in the form of the Supplementary Financing Program (SFP). Here the Treasury Department would issue SFP bills, increasing its borrowing from the market, that largely functioned like Cash Management Bills (a particular form of treasury bill, a short-dated government debt security). The major operational difference for SFP bills were their placement in Federal Reserve accounting. SFP proceeds were a liability of FRBNY in an account that was detached from accepting any tax receipts or paying government obligations.

“The effect of issuing SFP bills was to further drain reserves from the banking system since their purchase by dealers transferred cash from bank reserves to this inert Treasury account at FRBNY. Again, like the reverse repos, the SFP was a collateral creation and dispersal procedure – less “cash” reserves, more high quality collateral. In both cases, the Fed acted as intermediary and transmitter of high quality collateral into the marketplace at the expense of reserves.

“At its height in October 2008, the US Treasury had issued $560 billion in SFP bills, an amount nearly double the total Federal funds volume.”

In this newer iteration of the 2008 measures, the Fed no longer needs the SFP bills from the Treasury since it has acquired a massive “silo” of treasuries through QE’s. All that is left is a legal bridge to non-banks, allowing them to participate so as to not push the federal funds or repo rates below target (or to flood the t-bill market with funds, pushing t-bill rates below zero again). So the reverse repo plan would give non-banks the option of “investing” “money” with the Fed (collateralized by the Fed’s silo of UST) rather than below-target/floor rates in the open money markets. Controlling the non-banks would, theoretically, give the Fed full ability to enforce that intended rate floor (fixed rate tenders). I am not arguing here that additional control over short-term rates is a “good” thing, only that it is consistent with what the Fed aims to achieve.

It would also provide a channel for collateral to flow into the marketplace at the Fed’s discretion. Since non-banks and banks alike can bid for however much they wish at these reverse repo auctions (full allotment), they would then possess enough (theoretically) collateral to satisfy market demand. In other words, the Fed controls the margins of the US treasuries in its balance sheet inventory so that collateral is “priced” not to yield negative rates, or even below the IOER or whatever policy target it seeks. Right now, since the effective federal funds and the GC repo rates trade below the IOER floor, owing to the presence of non-banks, this would be a means to enforce further control over short-term rates and make the IOER floor an actual policy framework like the ECB “corridor”.

I am not as sanguine as some about how that might work, particularly in a climate of rising fear, but it does offer the possibility of using the SOMA holdings to alleviate a “market” collateral shortage.

The weak link here is that the entire plan is dependent on the Fed being correct in its perceptions of market conditions and that it can tailor its response to actual functions. It would still be dependent on non-market, bureaucratic decisions, the kind made during the months of tension before actual panic in 2008. It would also introduce an additional collateral “rental” fee that might not be calibrated correctly. In short, this plan depends on the Fed to correctly surmise rough patches and their causes, and then correctly deal with them in effective doses of policy. I don’t see what confidence that inspires.

Furthermore, it is another case of fighting the last war. The next liquidity event might disrupt funding markets in new ways (derivative markets, for example), just like 2008 was something completely unanticipated by the policy infrastructure, and then unappreciated as it unfolded in real time. In fact, the Fed still may not have a firm grasp on that last crisis, owing in no small part to a real lack of usable information because of dramatic complexity and intentional opacity. Asymmetic information was certainly a problem then, and it will likely be a problem in future episodes.

Beyond that, there is no means to flow SOMA collateral into global dollar markets. A distressed bank in India looking to fund that country’s trade deficit cannot directly obtain dollars from the eurodollar market owing to a lack of collateral flow or direct swap line. In other words, the dollar market, particularly repo, is still fragmented. For India and Brazil to gain a swap with the Federal Reserve would be conditional on a number of non-market factors, including the Fed’s perceptions about how the “markets” would perceive such a policy change. For most of these policy measures, they cannot be justified without a crisis first, for fear of creating a crisis via preventative policy.

The reverse repo facility is an attempt to address systemic weaknesses exposed five and six years ago, cloaked in the context of thinking about an exit from QE. Instead, it is a half of a liquidity bridge that still does not fully solve fragmentation, but at least the Fed will (theoretically) have more control over short-term money markets. That can’t be a bad thing, right?

Click here to sign up for our free weekly e-newsletter.

“Wealth preservation and accumulation through thoughtful investing.”

For information on Alhambra Investment Partners’ money management services and global portfolio approach to capital preservation, contact us at: jhudak@4kb.d43.myftpupload.com

Stay In Touch