Consistency perhaps should not be expected in rationalizing the emotional and illogical. It is easy to accept the premise that because everyone else believes something it is true. The wisdom of crowds always seems wise in the moment, until the “obvious” is revealed in gory detail.

I say “obvious” only as a countenance for James Bullard, President of the St. Louis Fed. In August, Mr. Bullard was certain there were no current bubbles to concern current Fed policy. While he was engaged in the epic debate of taper vs. non-taper, coming from the “deflationist” side, his views on this obviousness were rather striking and unambiguous. The Wall Street Journal quoted Bullard’s thesis as,

“He said there have been ‘two gigantic bubbles’ in the U.S. economy in the last several decades: the tech bubble in the 1990s and the housing bubble in the 2000s. The first ended relatively benignly, while the second was ‘a complete disaster,’ he said.

“The bubble issue is a very alive and very salient issue for the FOMC, he said, but both the recent bubbles he mentioned were obvious when they were at their peak. ‘I don’t see a bubble of that magnitude right now,’ he said.”

There has to be some consideration for Mr. Bullard “talking his book”, particularly as it relates to his monetary priorities. We might also notice the sneaky qualification, “of that magnitude”, that is an “obvious” hedge to his view. But after the September non-decision on taper, he is still talking about the “obviousness” of bubbles.

To accept his premise is to discount mania. If bubbles were so obvious, then they would never occur except in the risk of not being the Greater Fool. But while some acknowledge that risk, most charge headlong into the craze with little or no reservation. Or, more precisely, it is the rationalizing of why risk is overstated, over-emphasized or just plain non-existent. It is the rationalizations that create and sustain bubbles, and their primary effect is to render the bubble un-obvious.

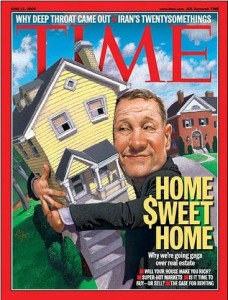

It’s no surprise that the Fed would be unable to view this intuition because their entire formulaic approach needs quantification. Yet there is no developed measure for insanity, mania or self-delusion. This applies not just to investing, but the monetary distortions of the real economy. In the 2000’s, how many otherwise sane people quit their jobs and followed the allure of “easy money” to flip houses and condos? It was a massive waste of resources, including time and labor that could have otherwise been diverted to productive and economically beneficial endeavors.

It’s no surprise that the Fed would be unable to view this intuition because their entire formulaic approach needs quantification. Yet there is no developed measure for insanity, mania or self-delusion. This applies not just to investing, but the monetary distortions of the real economy. In the 2000’s, how many otherwise sane people quit their jobs and followed the allure of “easy money” to flip houses and condos? It was a massive waste of resources, including time and labor that could have otherwise been diverted to productive and economically beneficial endeavors.

These flippers followed on from the day traders that sprung out of the “obvious” dot-com bubble. Again, they risked their livelihood on the chase for “easy money”. More to the point, whatever they saw they rationalized under the cover of self-delusion because they wanted the allure of easy money to be “real.” That everyone else was doing it was only a more potent form.

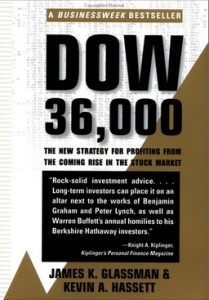

In September 1999, respected economist Kevin Hassett, not surprisingly a former senior economist with the Federal Reserve Board, and James Glassman, a business column writer for the Washington Post, published Dow 36,000. The premise was simple, that stocks were heading much higher and the authors had the math to prove it.

“Market analysts and media pundits have also persistently warned that stocks are extremely risky. About this they are wrong too. Over the long term stocks in the aggregate are actually less risky than Treasury bonds or even bank certificates of deposit. Although the experts may not be very good at predicting what the market will do, they are brilliant at scaring people—not out of malice but out of a profound misunderstanding of stock prices. Whatever their intentions, they have performed a terrible disservice to millions of investors by frightening them away from the market.”

The book became a best seller overnight, fitting the age into which it was unleashed. The book is now emblematic of that era precisely  because it was not all that unusual. The only originality was the manner in which the rationalizations were presented, but more or less it reflected the mania of the time and justified it with a veneer of econometrics and financial “science.”

because it was not all that unusual. The only originality was the manner in which the rationalizations were presented, but more or less it reflected the mania of the time and justified it with a veneer of econometrics and financial “science.”

In February 2011, Mr. Glassman wrote in the Wall Street Journal what sounded like an admission of the obviousness of hindsight (rather than the foresight of Bullard’s formulation).

“Yes, stocks bounced wildly up and down, but your job as an investor was to hang on and collect your reward for perseverance at the end of the ride. So, like most sensible financial advisers, I told readers to tilt their retirement portfolios strongly toward stocks—but with an extra large dollop of optimism because stocks at the time seemed undervalued.

“I was wrong.”

It seems Glassman underappreciated the effect of bubbles, and further the bear markets that inevitably follow them.

“In theory, historical averages show that stocks are a good buy if you can hang on through the miserable periods. But most investors find that excruciatingly difficult to do—a fact that I never fully appreciated in my 30 years of writing about investing.”

There is a little bit of a dodge in that “admission”, particularly the last sentence. In his heart, he still clings to the notion that “buy and hold” is the right strategy even through the up and downs of a bubble system. But it is precisely the “downs” that matter in the entire affair of investing in secular bear markets. The financial crisis that began in 2007 relates exactly to the fact that bubbles are not obvious, particularly to those that create them, and that the market drawdowns are not simply “pain” to be weathered. Market declines such as this bubble cycle, the undoing of the artificial “bull” markets, are fatal to long-term investors.

Instead of allowing markets to find a general clearing level, after much financial pain, policy instead jumped unto the breach in order to arrest any declines, believing that financial reversal is akin to deflation (enter Bullard). So rather than one cycle of boom/bust, we are now working on the third in succession.

As if on cue, Glassman returned to the Dow 36,000 thesis this past March. He wasn’t wrong, you see, about the ever-rising stock thesis and buy and hold, only in timing.

“We wrote in the introduction that ‘it is impossible to predict how long it will take’ to get to 36,000. Then, in the same paragraph, we rashly made a guess anyway: ‘between three and five years.’

“Today, the far edge of that time frame is clearly in reach. From its low of 6,547 on March 9, 2009, the Dow has risen 117 percent. Another 117 percent in four years would put it at 31,022, just 16 percentage points shy of the magic number.”

So Dow 36,000 is within reach and the rationalizations that drove it in 1999 were only delayed. Glassman appeals to better growth, obvious in his faith of monetizations, but also provides a convenient rationalization for resurrecting the original thesis.

“One way stocks could jump to 36,000 quickly would be for fears to subside and P/E ratios to rise. Assume that earnings yields fall to 5 percent. That would mean P/E ratios would go to 20, a boost of 50 percent in stock prices, assuming constant earnings.”

There is obviously no bubble because PE’s can rise to 20? That is utter nonsense, not the least of which because it is a meaningless tautology. It’s like saying the Dow can get to 36,000 because a lot of people will want to own stocks.

Worse than that, the idea of stocks always rising, and thus ignoring the bear markets, is foolish precisely because it discounts the effects of time and compounding. The worst part of the bubble cycle is not just that they burst, but they set you back in terms of time. For example, despite recent highs in the markets, it took years to claw back the 2007-09 losses. Going back to the publication of Dow 36,000 in September 1999, the current high on the Dow of about 15,600 yields about a 42% raw return. That doesn’t sound bad, but it represents only a 2.5% compound annual return – a pittance given the risk.

Let’s assume that this current market rallies because of the tautology presented by Glassman. If the Dow were to achieve 22,000 in another four and a half years, a double from the original publication, it would still only represent a 3.8% compound annual return going back to 1999. Further, we can assume that Glassman is right about a Dow 31,022, and again the compound annual return is fully underwhelming: 5.7%.

By way of comparison, an investor could have purchased a 20-year US treasury bond in September 1999 yielding 6.5%. That would have outperformed stocks for the entire period, even assuming Glassman’s new Dow target of 31,022 – and that simple bond yield comparison assumes absolutely no compounding of interest returns.

In other words, where the market ends up is much less important than how long it takes to get there. There is a world of difference in bubble markets because they introduce the risks of getting left behind, even when markets actually achieve some magical threshold. The reason so many investors make that mistake is because bubbles are not fully obvious as there will always be someone to convincingly rationalize risks away. It is perfectly human to be susceptible to this form of delusion because we want to believe money is easy, and that it isn’t too good to be true. Bubbles are not obvious because of the psychology of crowds. That is why snake oil sold so well before, and will continue selling easily in its more modern, monetary incarnations.

Bullard is either fooled himself, or a full-throated pitchman. Prudence demands this recognition in both investing and the monetary reckoning.

Click here to sign up for our free weekly e-newsletter.

“Wealth preservation and accumulation through thoughtful investing.”

For information on Alhambra Investment Partners’ money management services and global portfolio approach to capital preservation, contact us at: jhudak@4kb.d43.myftpupload.com

Stay In Touch