The conventional view of asset bubbles is that they are difficult to discern even after the fact. The current policy position is one of bubbles that are “obvious.” Looking back at the late 1920’s, there is no doubt it took a similar track to that seen in the late 1990’s. But that, by itself, does not necessarily denote the presence of a bubble. After all, as any good monetarist will tell you, stock prices are supposed to rise.

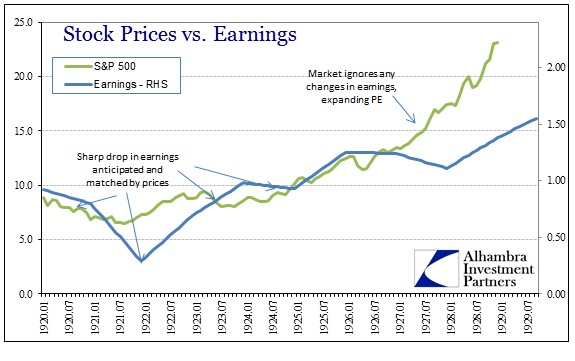

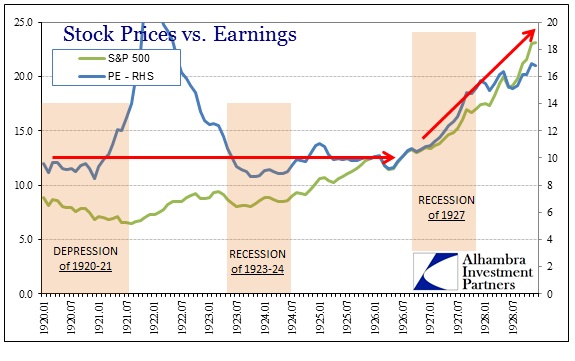

It is clear from the market’s behavior that something was altered around 1927, maybe as early as the middle of 1926.

What is telling about the divergence of prices against earnings is that the stock market completely ignored the recession of 1927. Earnings declined but prices shrugged it off entirely. Maybe that was to be expected given the relatively mild business setback, but as the chart immediately above shows, the market multiple changed trend and never looked back. What was a pretty solid relationship between prices and earnings shifted dramatically toward rapid expansion, and the race was on all the way to October 1929.

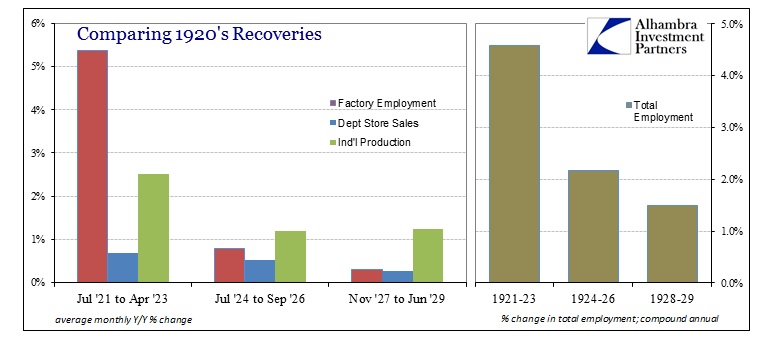

Looking at the economy at the time, there was clearly a decent expansion, in broad terms, despite the two recessions during the decade. But the direct period in question, where earnings multiples surged on price inflation alone, was nothing special as it related to economic growth that might justify rapid acceleration. Again, the common narrative of the “roaring 20’s” is somewhat misplaced, as growth in the economy actually tapered off toward the end. The recovery after the ’27 recession was significantly weaker than that after the ’24 cycle (and very much so after the depression of ’20-’21, which was to be expected given symmetry).

By every major economic measure of the time (using contemporary data), the underlying economic conditions were not readily supportive of such massive multiple expansion and fast moving prices. It is here, however, where the psychology narrative takes over in the orthodox view, that euphoria was just so intense that it overrode common sense and any previous restraint that was so evident earlier in the decade.

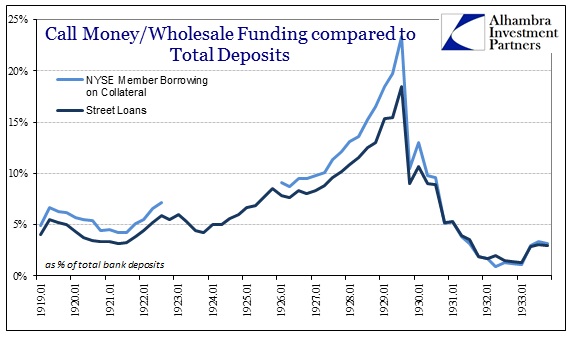

The Federal Reserve Bulletin from December 1928 notes something strange about this period.

Demand for loans for commercial and industrial purposes reached its seasonal peak at the end of October and declined somewhat in November, and the banks also further reduced their holdings of investment securities. Collateral loans, however, which includes loans to brokers and dealers in securities, showed a rapid increase in November, accompanying the growth in volume of transactions on the stock exchange and the continued rise in security prices. The recent increase in security loans, which for the past three months has amounted to over $500,000,000 at member banks in leading cities, has carried the total to a level above the maximum reached last summer.

That may sound quaint next to today’s trillion dollar programs, but $500 million was an immense sum for the period. To put that into perspective, at the end of 1928 the total amount of Street Loans to brokers in this call money interbank market was about $5 billion, or an astounding 15% of the level of total deposits at all Federal Reserve member banks.

By the peak in 1929, call money loans had grown to an unthinkable one quarter of all member deposits (or, on the asset side, the same proportion of total lending and securities). By the time of the crash in October 1929, brokers had reported $8.5 billion in call loans outstanding.

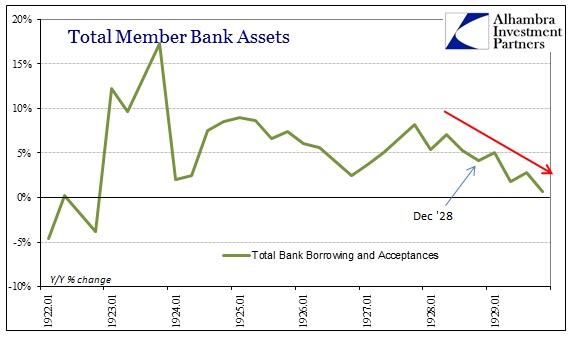

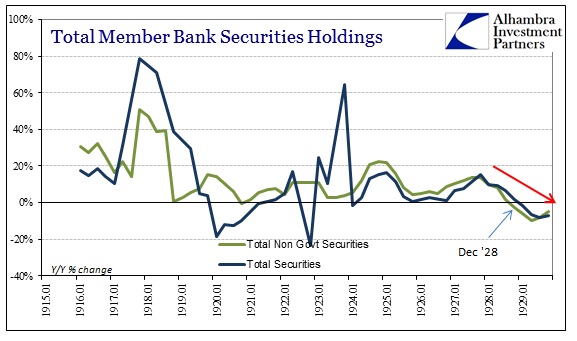

That, however, isn’t the part that stands out, at least in the context of this inquiry. While call money lending in this wholesale market had shifted so immensely as to deserve special comment by the Fed at the end of 1928, that was, as the Bulletin documents, in sharp contrast to bank portfolios elsewhere. Banks outside of the call market were beginning to shift assets.

The data from bank assets matches the observations from the real economy – the last few years of the decade were unspectacular to say the least (which also shows up as relatively slight declines in wholesale prices after 1927). In many data points you can even make the case that the economy was rather lackluster in absolute terms as well as in comparison to the previous “golden” years. That is particularly true as it was very unusual to see banks resort to liquidity like this by the outright selling of securities; in fact so unusual as to be previously associated with only recession (and there wasn’t even selling of the total class of securities during the worst days of the 1920-21 depression).

Most people with even a rough familiarity with global monetary conditions in the 1920’s are aware of Germany’s experience with hyperinflation – the initial rise of Hitler, Nazi’s and all that. However, the French franc nearly followed the mark into total oblivion in the years immediately after Germany’s monetary collapse. France, though a victor in the Great War, was also an unmitigated mess by mid-decade. As with Britain, the Great Powers had turned away from the gold standard to pay for war, but began to move back in that direction as conditions under the floating currency regime failed to reignite economic vigor (in fact, ter Meulen was all about trying to merge floating currencies with gold via international artificial monetary creation, to preserve some parts of the former by a looser anchor to the latter).

Whereas the Bank of England overvalued the pound (on Churchill’s desire to gain prewar parity as a matter of national pride and significance) upon moving back to the gold standard in 1925, the French franc was severely undervalued owing to its own peculiar circumstances. In both cases, and with the United States fixed in the middle of it all, this was not the traditional gold standard with its “rules of the game.” Instead, this was merely a further expression of what Hoover had recognized and embraced, namely a transitory period where gold was still relevant but central banks were afforded far more liberty with “flexibility” (to use Bernanke’s phrasing).

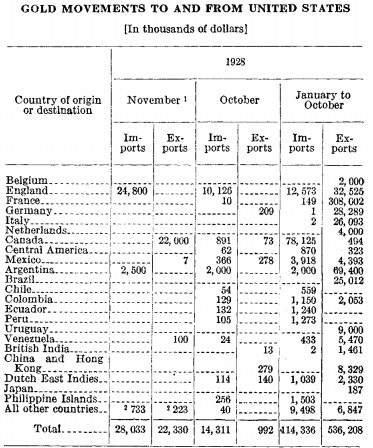

As a consequence of the franc’s parity, gold that had moved to the United States during the uncertainty of the floating currency period now began shuffling off to Paris (and other geographies).

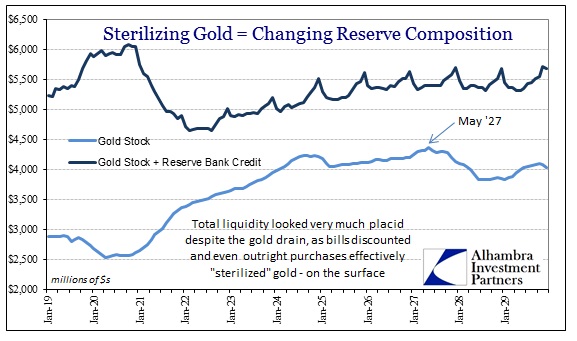

The new and heavily devalued par value of the franc was set in December 1926, and was formally affixed as such by the Monetary Law of June 1928. As you can see in the chart immediately above, gold movements are coincident to the liquidity situation in bank security holdings, with the majority of the gold drain beginning in the second half of 1927.

That same December 1928 Bulletin totaled gold exports to France at an enormous $308 million in only the first nine months of the year. The full picture of monetary movements and liquidity, however, is more complicated than that.

The Bank of France had been using its newfound “flexibility” out of the franc crisis to counteract both gold and currency movements before and after the December 1926 parity announcement. Gold had already begun to drain from London, causing enough furor there to get the Bank of France to engage in currency swaps to limit the effects on the French side. In other words, the Bank of France was selling pounds and dollars forward, accumulating reserve positions of “currency” in all directions.

There has also been, particularly since the beginning of 1928, a substantial flow of funds from France to Germany. These funds were mostly dollars and sterling which formed part of the considerable amount of foreign currencies lent by the Bank of France to the French market, and borrowed there for relending to Germany.

Foreign reserves often conjure images of physical currency stacked in neat bundles inside a central bank vault, but in reality this was a ledger system where deposit accounts were debited and credited at private banks. In the case of dollar reserves, the Bank of France held accounts with both Federal Reserve banks (particularly FRBNY) and, more often, private American banks. Such reserve accounts were supposed to facilitate gold transactions, but the absence of hard gold rules meant exactly this kind of behavior – using reserves to manipulate and even circumvent market determinations to conduct national policy (central policy control takes precedence over markets).

The Monetary Law of June 1928 ended the Bank of France’s swap interventions into currency. Those that the central bank had engaged in late 1926 and early 1927 now matured, meaning that the Bank of France had to buy and accumulate dollars (and sterling) in reserve accounts at US banks (and British) in addition to gold movements toward Paris. These two pressures on US banks were the primary driver of liquidity needs in 1928 and 1929.

Under the traditional gold standard, the Fed (or more favorably, the private banking market that existed before the Fed) would have had no recourse but to allow interest rates to rise under such conditions. That was the balance gained by a true gold standard, as imbalances in trade and finance served to keep economic flows and domestic credit in check. Had the traditional rules been observed here in 1928, the US downturn from the 1927 recession would no doubt have been much worse and the recovery thereafter short-circuited. The entire banking system would have been forced to deleverage perhaps as much as it had in the 1920-21 depression (largely since so much gold had flowed to the United States before and after, an imbalance itself that needed to be cleared up – more on that later).

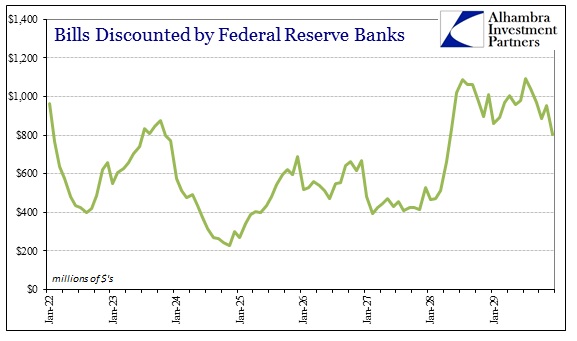

But this was the “golden age”, and the Federal Reserve would have none of the “rules of the game.” Having already engaged in open market actions in direct aid of the Bank of England’s attempt to manage the pound in 1925 and 1926, the US central bank responded to that impulse of bank deleveraging by kicking monetary policy into overdrive. Where gold was being removed largely to Paris, the Fed filled in that hole with “Federal Reserve Credit” to maintain a uniform appearance of systemic liquidity.

The huge scale of monetary measures like those of the early part of 1928, again, was usually reserved for recessionary periods (or war). The Fed was convinced that it could and would “steer” the US economy out from under the gold standard’s creeping “deflationary” pressures, keeping recovery intact and perpetuating it indefinitely.

There is no such things as a perfect substitute, and though liquidity (or its appearance) could be maintained by Federal Reserve Credit in the loss of gold, it isn’t as straightforward as all that. The changing content of the base of the bank pyramid also changed the character of allocation. There is a market determination of gold flows that cannot be replicated by monetary policy actions. Banks were well aware of gold movements, and even as the Fed filled in the monetary hole created by gold exports they were doing so with a less certain and stable substitute. Instead of lending, or buying longer-term securities, banks might be tempted toward liquidity itself owing to the perceived difference between gold-based money and Fed-based money.

That is just basic sense in bank management. If liabilities are perceived to be less stable, especially systemic liquidity, banks will endeavor to create the same matching on the asset side. Replacing gold with Fed-induced interbank credit would not be the same thing as the system not losing gold.

What really happened is that banks shortened their maturities despite this centralized constant assurance of liquidity. The banks in the real world dealt with the changing character of the money pyramid in exactly that fashion – longer-term securities were sold off (as noted above) while interbank balances, especially street loans from correspondent banks, rose precipitously. So where the Fed appeared to ably “target” the total interbank liquidity markets, making up for gold losses, that doesn’t account for the distribution or allocation of bank assets (and thus liabilities). And it certainly does not account for foreign “reserves” that were floated here. This would have a profound impact.

Click here to sign up for our free weekly e-newsletter.

“Wealth preservation and accumulation through thoughtful investing.”

For information on Alhambra Investment Partners’ money management services and global portfolio approach to capital preservation, contact us at: jhudak@4kb.d43.myftpupload.com

Stay In Touch