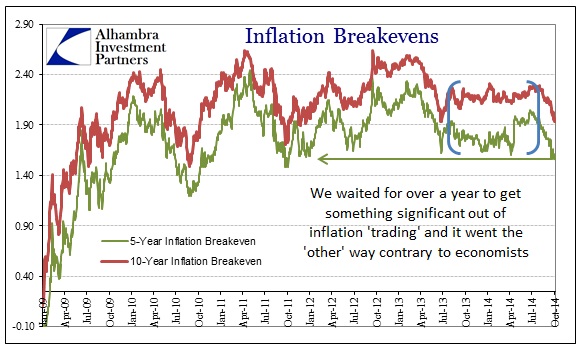

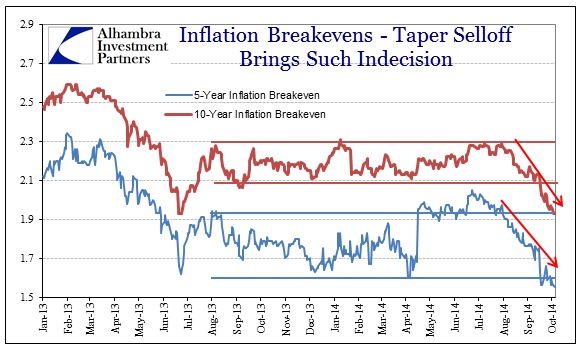

Going back to the yearlong period (more like fourteen months) where inflation breakevens fell into the apparent nothingness of being almost wholly range-bound, I surmised that the artificial placidity had to do with the inability of market participants to let go of their normally all-consuming faith in Fed optimism. On the one side, economists, particularly the central bankers all over the world that saw nothing but clear sailing, maintained that recovery was at hand and thus “inflation” would eventually rise. If the “market” view prevailed upon that optimism, breakevens should have broken upward.

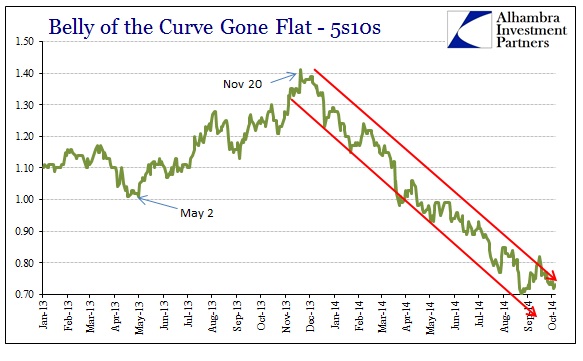

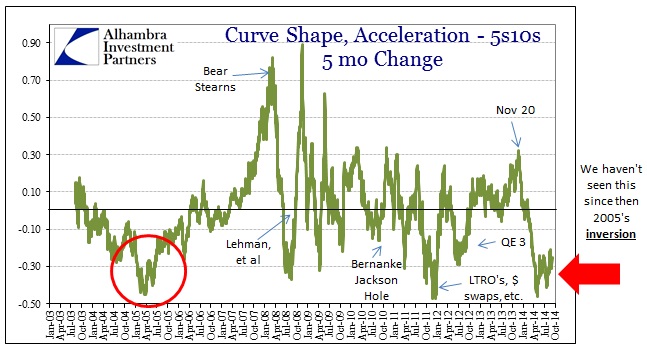

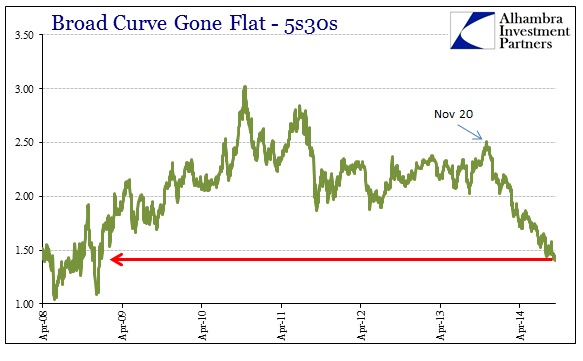

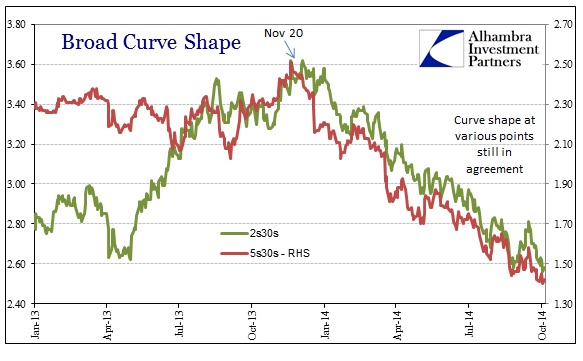

Standing in direct opposition to the recovery narrative was the rest of the (non-corporate) credit markets, particularly the dissemination of yield curve positioning. So where economists and central bankers were positive toward growth, and thus if only indirectly toward higher “inflation”, the broader bond market was decidedly not. That offered, to me, the most compelling reason for breakevens to simply do nothing; to wait and see which view ultimately might prove more irresistible.

Given the waning prospects globally for growth, this includes the US though nobody seems to want to mention that, there is little surprise which way breakevens have eventually sided. It is not just that growth has failed to materialize, it is that central bank promises are falling by the wayside now almost as quickly as they have been made, and so credibility of efficacy in monetarism is also waning. You can only cry “recovery” so many times, but if after seven years the risks are still weighted on the downside then reassessment in credit markets is the least of the problems.

In that important respect, the bearishness of the bond curves that has been showing for almost a year itself contradicts the earnestness to which the stock market is “preferred” by comparison. Policymakers will not hesitate to proclaim stocks as some kind of barometer for economic health, but curiously never seem to hold much for the far larger credit markets that are more directly related to such fundamental factors. In that case, given the relativity of interest rates to ZIRP, yields are pretty much irrelevant to the PR (moving up sharply as they did in 2013 was not “helpful” to the narrative, nor is the flattening and lower rates in 2014, so ignore it all!).

So it is very interesting to see the FOMC’s “evolution” on prospects during this same period. Back at the December FOMC meeting, the one that initiated actual taper rather than threats of it, the “participant’s views on current conditions and economic outlook” contained the following expectations:

The projected improvement in economic activity was expected to be supported by highly accommodative monetary policy, diminished fiscal policy restraint, and a pickup in global economic growth… [emphasis added]

Just one month later, in January 2014, the FOMC “participant’s views on current conditions and economic outlook” wrote nearly the identical:

That expansion was expected to be supported by highly accommodative monetary policy, a further easing of fiscal restraint, and a modest additional pickup in global economic growth… [emphasis added]

Suddenly, “global growth” had turned “modest.” By the time of the March FOMC meeting, such language was completely eliminated (now under the heading “the outlook for economic activity”).

Nonetheless, participants pointed to a number of factors that they expected would contribute to a pickup in economic growth this year, such as an easing of the headwinds that have been weighing on growth, including diminished restraint from fiscal policy; rising household net worth and highly accommodative monetary policy also were expected to contribute.

“Global growth” was disappeared from the “outlook” entirely as a “tailwind”, instead replaced by rising household net worth (oh that favorable stock inflation), with only vagaries and very benign references, they assure you, to Ukraine and China.

…a larger-than-expected slowdown in economic growth in China could have adverse implications for global economic growth. In addition, it was noted that events in Ukraine were likely to have little direct effect on the US economic outlook but might have negative implications for global growth…

The April references about “global growth” were largely the same, including nearly the duplicate allusions to China and Ukraine. By the June FOMC meeting, Iraq was added as a potential negative factor for “global growth”, as was a sudden concern for “low inflation” in Europe that had been low and lowering for almost three years.

As of the latest meeting, September 2014, the FOMC’s global growth assessment has totally splintered.

Foreign economies continued to expand in the second quarter, but with significant differences across countries.

That is quite a difference from the December 2013 expectation for a monolithic “pickup in global economic growth” (the narrative). Now the FOMC is beginning to see the dollar as another potential “headwind” which may have “adverse effects on the U.S. external sector.” None of that changes their outlook for the US, at least not yet though that should be expected given the progression here, which they still feel is more dependent on less fiscal drag, higher household net worth and that old standby of “highly accommodative monetary policy.”

Of course, the major flaw connecting all of these indications is that US economic fortunes are very much tied to “global growth.” Thus a slowdown and downside risks for the world economy apply liberally with the US not in isolation as these closed-system adherents still contend. If global growth is decidedly “off”, then that describes very unfavorably the US economy as it exists as the largest end market.

Given that none of those three factors (less fiscal drag, higher household net worth, highly accomodative monetary policy) have provided the recovery necessary to date, it might make sense to look at the bond market for economic guidance rather than stocks – where even the FOMC continued to reference “stretched valuations” as potentially undermining “financial stability.” Again, I think that reinforces the idea of what breakevens were and are indicating, that the credibility of FOMC economic expectations (indeed of all central bank promises) has been severely diminished. That is particularly hardened now that “global growth” has become fully undone and all that is left for policymakers to base their expectations is the same bland generalities they have been consistently using for years to no avail.

If highly accommodative monetary policy has been applied globally (which even the Fed would admit) and global growth expectations have so suffered as the calendar winds further anyway, reasonable downward extrapolations apply including domestically. That seems to be the message (non-corporate) bonds have been sending for the whole of this period in question, only now it is gaining acceptance athwart the FOMC’s optimistic-sounding downgrades.

Stay In Touch