I usually ignore sentiment surveys as, to reiterate one more time, they do not mean what people think they mean (and certainly not how they are used). The ISM Manufacturing Survey, for example, has been on fire for most of 2014 in an almost exact mirror of 2011. And just like 2011, that told us very little about the state of the US economy even at that moment, especially as what followed then was a dramatic and worldwide economic slowdown just around the corner (in direct opposition to how economists were reading that cycle “high”).

So I have to credit my colleague Joe Calhoun for wading into the Markit Survey to notice not just its measure but its own interpretations. This is nothing short of extraordinary:

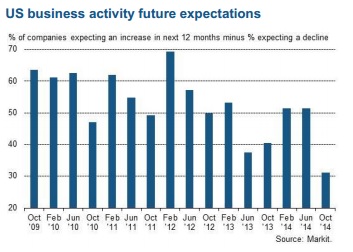

U.S. companies reported the lowest degree of confidence since the survey began in late 2009, reflecting domestic concerns and a subdued external demand environment.

Of course, Markit being what it is could not just let that stand, following up with conjecture about how the US is not as bad as Europe and operating as a “key growth engine across world markets.” Like the survey itself, I don’t think Markit’s economists mean what they think they mean in making such a statement. I would agree with that sentiment, which is precisely the problem with the global economy.

The “key growth engine” in the US is faltering, “reflecting domestic concerns”, thus the global economy is faltering (with Europe and Japan playing the same part only a little further down the road). That October 2014 decline in the survey is not due to Europe or Japan’s problems, try as they might to suggest decoupling as an actual process.

As if that were not enough “unexpected” weakness, even in sentiment, Markit also published its global version.

Clouds are gathering over the global economic outlook, presenting the darkest picture seen since the global financial crisis. Companies’ hiring and investment intentions have both fallen to post-crisis lows alongside the bleakest outlook for future business activity seen over the past five years…

Of greatest concern is the slide in business optimism and expansion plans in the US to the weakest seen over the past five years. US growth therefore looks likely to have peaked over the summer months, with a slowing trend signalled for coming months.

In other words, Q3 GDP revisions don’t much apply to anything other than “the narrative.” But what is truly worrisome is that this is playing out exactly like the process in 2011, which was problem enough then but this version starts from a much weaker base (at least there was the hint of quick growth in 2011 and hopes for future acceleration were at that time largely unsoiled on the surface). If the cycle repeats (mini-cycles within the larger cycle) it will do so still after every central bank around the world has smashed prior limits in seeking out actual recovery.

What is left for them to do, global Abenomics? Even that has lost much of its following in the real economy (academia remains consistently enthused).

Optimism in Japan continued to lag behind that of the US, UK and even the Eurozone, dropping to a two-year low to suggest companies have become increasingly disillusioned with the potential for ‘Abenomics’ to boost growth, although there are signs that Japan’s recent deflation-beating policies will continue to drive prices higher next year. [emphasis added]

The last part of that quote is why economists are so utterly incapable of creating what theyseek most. Change the word “although” in that sentence to “because” and it starts to make sense. Instability is not what Japan needs after a quarter century of nothing but that (and despite philosophical equivocations, twenty-five, and really thirty, years of instability is not itself a derived form of stability), a feature that is more global than economists are aware.

There is a growing sense of failure and disillusion in monetary power and the once-unquestioned faith in central bank if not pure omniscience than something just short. This explains the “sudden” appearance of Paul Krugman at these key monetary choke points, as the status quo is being passed back to “Keynes.” That is both an implicit admission of failure about the real economy and a reflection of what might be bearing down.

The cumulative nature of all these current results and the dark clouds gathering in sentiment, if not yet in “mainstream” numbers that still look somewhat positive, is not what central banks have been saying all along. Instead, this looks very much like a 30% or more decline in the price of oil and a deliberate pull-back in “dollar” leverage worldwide. The contours of the economic cliff are becoming more visible by the day.

Stay In Touch