The dissection of the economy as it exists right now is usually limited to a narrow cross section of only GDP and the unemployment rate. As long as both are moving in the “right” direction, even if relatively sluggishly, the mass conclusion is that a recovery is in force and will remain so absent any “shock.” Theoretically, that owes to both Milton Frieman’s “plucking model” (which suggests that an economy will of its own accord move toward its potential once “shocks” are removed) and the idea of “aggregate demand.” In the latter case, all that matters is that some economic activity takes place with no regard to how or why.

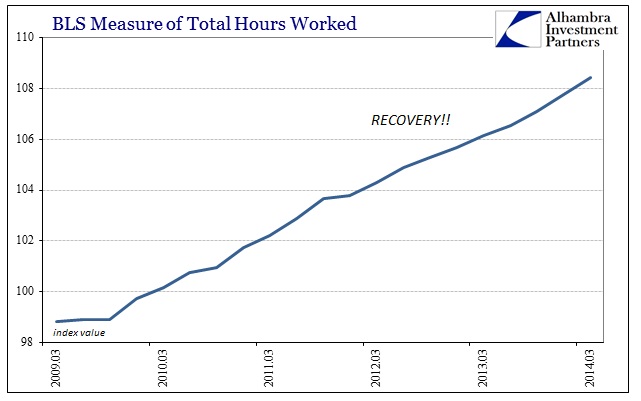

So the majority view of the current economy is as presented above. There was a nasty recession that ended sometime in the middle of 2009, and everything has been gaining ever since. Of course even the FOMC has admitted intermittently that the pace of “recovery” has been unsatisfactory, but that hasn’t changed the overall interpretation.

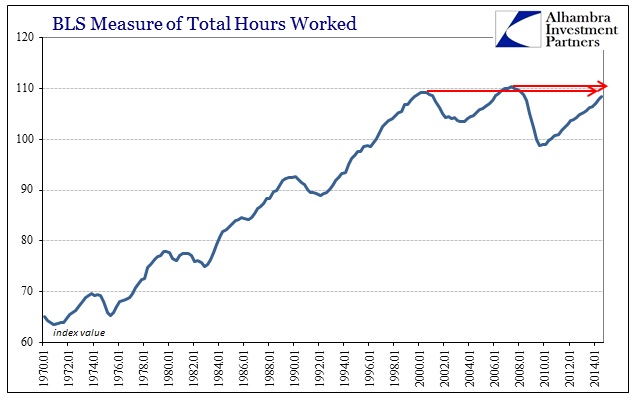

While the direction is nice and plays well in a limited role in terms of media dissemination of that narrative, it literally does not add up. Just viewing the labor market in a wider context shows that “recovery” has been absent as only the direction conforms to the idea. A true recovery is not just advancing, but doing so in a manner that rather easily attains prior levels of economic expansion (the plucking model has a great deal of validity).

It is that second criterion that invalidates the idea of recovery, and thus the current narrative about the economy. As I noted last week, the entire purpose of an economic system is labor specialization, so rising GDP may seem better than the alternative, if it doesn’t correspond to fulfilled labor advancement there is something very wrong.

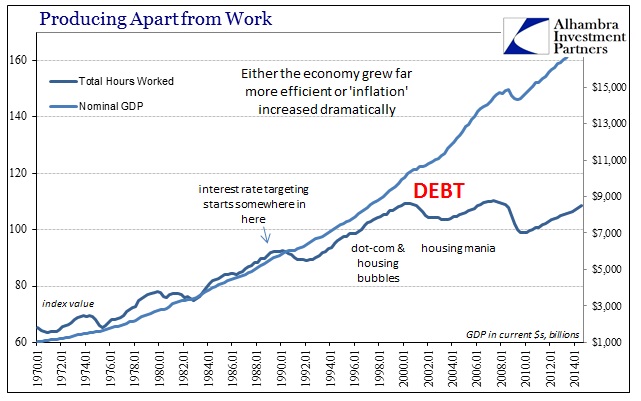

Indeed, that seems to be the case going back to at least 2000. The BLS’s alternate labor metrics, either full-time jobs or total hours worked, remain significantly below prior cycle peaks despite the almost seven and a half years of calendar distance. In the measure of total hours worked, which includes the participation problem, we are still (the latest figures are for Q3 2014) below not just the prior cycle peak in 2007 but also the one that preceded that!

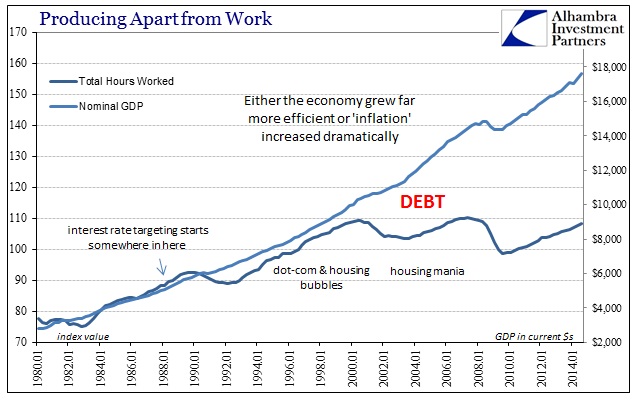

Just on a purely economic basis, stripped of modern, orthodox theory, that would more than suggest that the current economy is smaller now than it was even in the year 2000. However, that possible interpretation is countered by GDP.

GDP measures only the “dollar” volume of goods and services traded at a “value added” level. While total labor exchange clearly hit some kind of wall around the year 2000, the total “dollar” value of economic activity did not. That has left a tremendous divergence between earned income and this generic idea of “aggregate demand.”

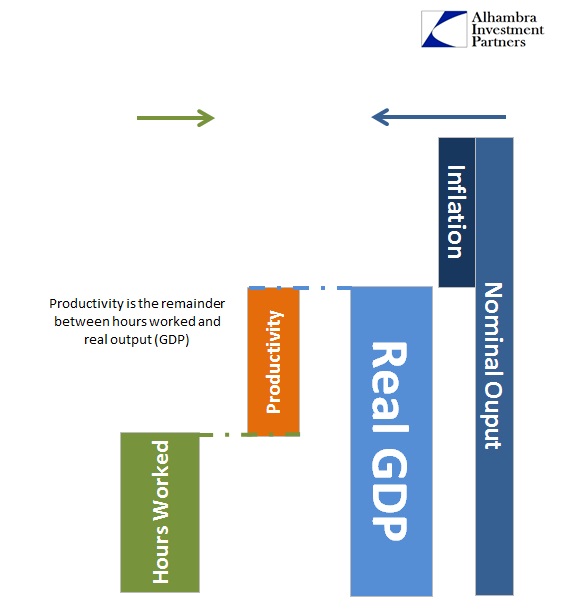

The constituent parts of GDP, and really the actual economy, include not just labor but also “inflation” and productivity. Such a divergence between labor and GDP is entirely possible, and might even be desirable, if productivity, for example, were to greatly increase. In other words, if labor produced a lot more per unit then the total output would greatly expand beyond just additional work levels.

But even if that were the case, that would leave economic circulation entirely different, at the margins, since “something” would need to fill that gap – if increased productivity flowed entirely to business profits than that would more than excite the previously dormant Marxists, including the sudden re-emergence (for the fifth or sixth time) of the idea that Marx was somehow prescient about capitalism’s inherent flaws toward its own demise. Aside from economic dogma, that would mean economic flow beyond labor would marginally be increasingly dependent on business activity; whether further expanded flow crept through productive means, such as capex, or ownership means, such as dividends and share repurchase. The latter would be far more inefficient (and also excite the neo-Marxists about “inequality”) and would lead to at least economic instability; while the former would actually keep profits from taking off and remaining that way.

In that respect, profits should act more like a phugoid cycle of self-correction.

The problem with “productivity” is that we don’t really measure it directly (nor is it at all clear how that might even happen). The current standards are to deviate somewhat from presented figures and merge hours and GDP. The BLS takes nominal GDP and alters it for a specific measure (mostly private output) and subtracts inflation to get “real GDP.” On the other side they have already constructed a measure of total hours worked, so that the difference between them is simply “productivity”; a plugline.

Another way of constructing that is to simply separate nominal GDP into these three constituent pieces. These three factors do, in fact, correspond to actual economic factors, as labor, price changes and productivity are how redistribution by capitalism actually works. The question now is whether or not the current measures still fit that definition given the difficulties in calculations and even theory (especially “inflation”).

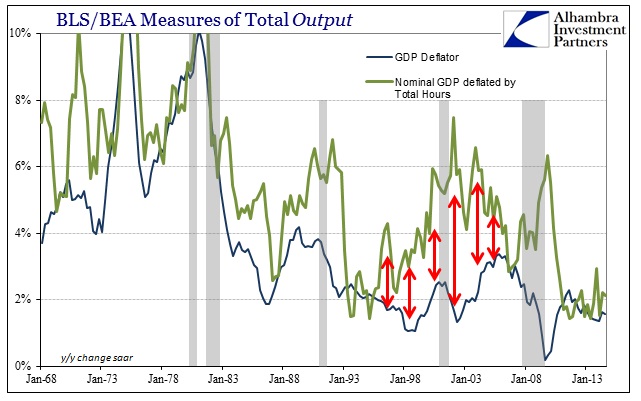

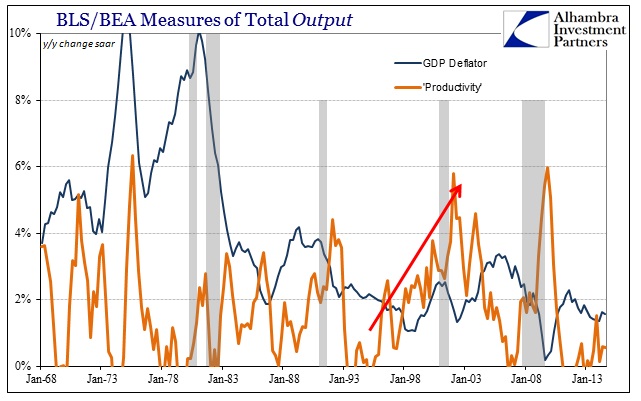

If you “deflate” nominal GDP by total hours (which does conflate separate data series, so take it FWIW) you can remove changes in the level of labor activity as a factor in GDP leaving only productivity and “inflation.” What is most noticeable in that view, shown immediately above, is how “productivity” (the distance between the green line of non-labor GDP and the blue line of “inflation”) seemingly grew sharply starting around 1995, continuing right through the middle of the next decade. I have redrawn that below, where the orange line represents the plug-factor of “productivity.”

The continued pace of “productivity” is far outside the historical norm, especially as it persisted not just for more than a decade but even through recession in 2001 (though mild). It was something that even the FOMC noticed, as Janet Yellen herself took time to remark at the May 2007 FOMC meeting (where they largely ignored and rationalized, through groupthink, the looming catastrophe):

But the hypothesis that the recent decline in productivity growth is mainly structural does not seem to me to square well with the broad range of available evidence. Recall that in the 1990s there was a whole constellation of evidence—including a booming stock market, robust consumption, and rapid business investment—that was consistent with a hypothesis of a lasting increase in the rate of productivity growth.

So here it was in May 2007, on the eve of the inauguration of the first phase of crisis that would lead to outright panic (if only among global banks), and Janet Yellen was still looking at the 1990’s as if it were something “normal” and indicative of “potential.” In the context of a debt-based bubble, as the dollar turned into the “dollar”, such productivity doesn’t actually make any sense. The increase in the prices of houses does not automatically lead to greater productivity, as the “wealth effect” even if it were to increase “aggregate demand” does not change that someone needs to produce something somewhere.

Take Yellen’s own formulation above – “booming stock market, robust consumption, and rapid business investment.” The last was, as it turned out, related to the first; unfortunately “rapid business investment” was too much related once that “booming stock market” completely reversed in a 60% – 80% disaster (depending on the index). Conspicuously, however, “robust consumption” remained almost totally undisturbed despite that grotesque rebalancing in stocks and business proclivities. In other words, none of it disturbed the housing bubble, only a minor delay, including the so-called gains in productivity.

How could “productivity” remain historically high even though there was a three-year gap where business investment was in total disarray?

Given the construction of the current thinking on productivity, perhaps it might be suggested that the increase in debt usage as a direct course of the asset bubbles were hiding “inflation.” The simplest explanation, rather than a mysterious and apparently unalterable advance in the productive nature of the US economy which somehow produced no benefits to US labor, may be that inflation has been “suppressed” during the period in which labor advancement has stagnated. That may not have been intentionally, but merely a byproduct of economic theory that doesn’t incorporate realistic complexity.

The idea is that corporate profits have been expanding far outside of historical norms and that has not led to, for the first time in history, robust expansion on the labor side. The reason for that is entirely simple, as high profits should lead to intense competition. Competitors enter any market where profits are really good, and in doing so require additional labor to make a competitive run (including innovation, which leads to the life cycle of businesses, and where labor expansion is truly generated by small firms that become big as they succeed). This is also a part of capex vs. financial “investment”, as heightened competition actually increases the need for productive investment since financialism is mostly useless in those terms (except if you buy out your competitor).

Thus, we can easily surmise, that any period where corporate profits remain so historically high (and labor so low) that natural competition is devalued or removed; i.e., redistribution. Inflation, broadly defined into asset prices, is one form.

The net effect of debt inside this trend is simply to keep it afloat whereas absent such “debasement” it would never last this long – Marx was right about that part, if wrong about everything else. In other words, “inflation” is not just a poor measure of what it is intended to measure, but as a concept it isn’t broad or nearly complete enough. The divergence between GDP and labor is redistribution being acted out in real phenomena, like corporate profits and debt, but that the statistics we currently use cannot discern the difference. And, like Janet Yellen so ably demonstrated just prior to the Fed’s second greatest historical failure, they don’t want to.

When the orthodox economists gather around their computers on Friday to celebrate the latest monthly payroll report, none of this will factor into their outlooks. For my analysis, the fact that the population/potential labor force has grown by 36 million since late 2000 and we still have less work taking place now means that the economy, without much doubt, is actually smaller by a significant amount. That would further explain why there is no “booming stock market” but rather serial asset bubbles, or, more precisely, serial asset busts. “Booming” anything related to assets is based on the creation of actual wealth, and, “inflation” aside, there hasn’t been anything like that to support and sustain such expansionary pricing.

The nesting of so much into corporate profits instead of labor is akin to an outbreak of inflation, at least in the form of redistribution. The economy can appear to be operating as usual, but the unsatisfactory pace and the instability of it all are instead more than suggesting the problems I outlined here. Something is very wrong with all of this, and unfortunately it remains so after more than two decades. That is a very scary thought.

Stay In Touch