I’ve had my suspicions for some time that December saw a(n) (il)liquidity event throughout the “dollar” system. The problem with that supposition is the lack of corroborating price action in riskier markets where you would expect the most impact. That was the pattern revealed by the end of the last event on October 15, where risky credit, especially corporate junk (leveraged loans and high yield bonds) and even stocks, took severe notice of a low and no bid environment. Downstream of that, issuance has been impaired.

But risky credit prices were not much perturbed, that we can observe directly, in this latest gyration. In fact, even the currencies we have come to view as proxies for this kind of dysfunction were relatively untouched (at least by the standards of the “tightening” of the dramatic swings in early December). By process of elimination, that left European factors as prime candidates.

That would certainly make sense on the surface, as there was no shortage of European drama in late December/early January. That starts with Greece’s political change (which was just a possibility at that point) followed by rumors of ECB QE, and then the utter upset of the Swiss franc. All of those factors are certainly represented in “dollar” positioning via European bank participation in both arenas.

Liquidity issues of a broad nature seem to feature almost always a collateral component. That would make intuitive sense even if you don’t have much working knowledge of interbank conditions, as funding “tightness” might at least force some collateral calls or just the additional secured lines of funding. And so a dramatic increase in collateral need is spelled out via “unusually” strong bids for UST.

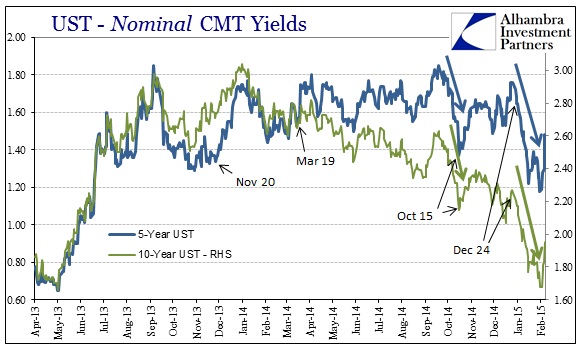

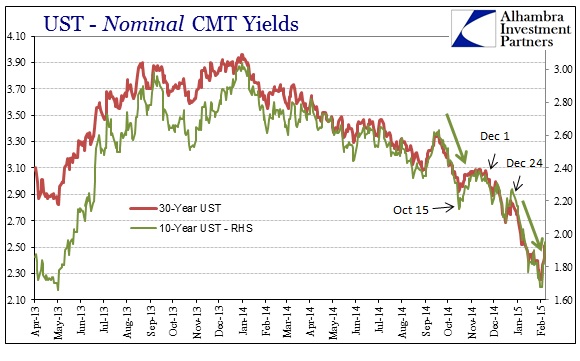

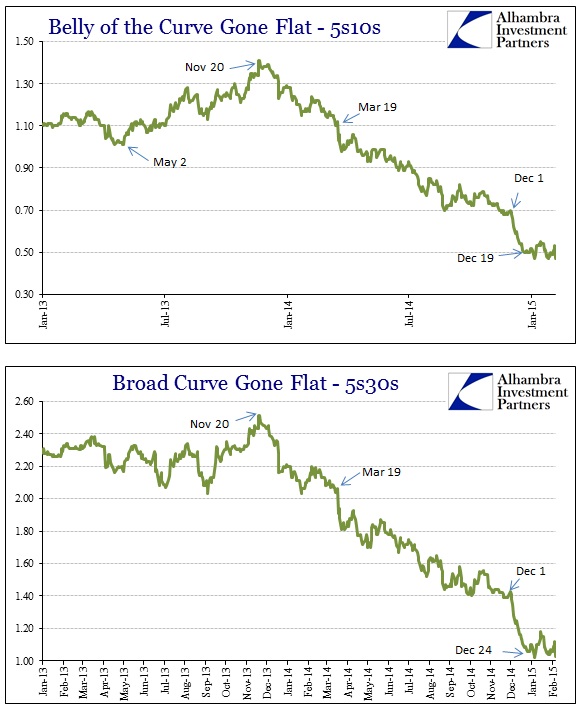

That was clearly the case beginning in late September as it led to the ultimate rupture on October 15. This follow-on heavy and sustained bid in UST was initiated just after the Christmas holiday. Nominal yields all across the treasury curve began to drop, and do so precipitously and in sustained fashion.

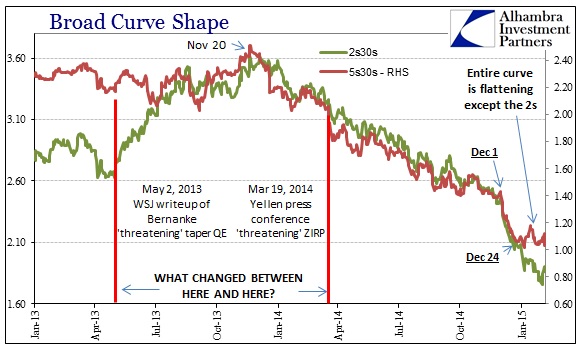

In terms of the overall curve shape, we see the dramatic increase in the flattening trend that developed on December 1 suddenly cease. That did not mean it reversed, only that shorter-term maturities now began to be bid alongside the outer maturities; in other words, the entire treasury complex came into high demand around the Christmas holiday.

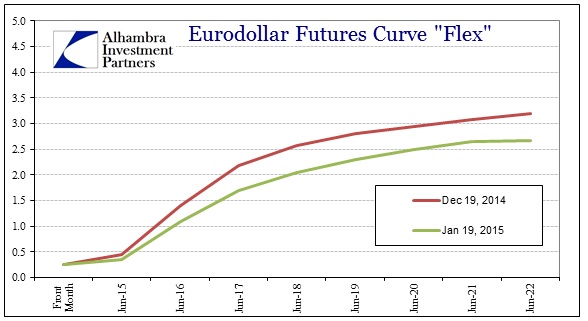

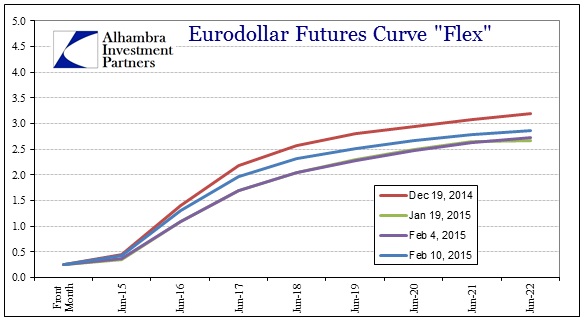

While I tend to think of that along the lines of collateral shortages and possible disrupted flow (repo fails were high again), that does not preclude the simple possibility of just “flight to safety.” That was further asserted by additional “flow” into the eurodollar curve, as around the same time the entire funding curve flattened in opposition to the “rate hike” narrative that was being pushed heavily by FOMC statements and mainstream “analysis” of the economy.

We also need to keep in mind that the Swiss National Bank’s removal of the franc peg occurred within this time frame, on January 15. This would all tend to argue that the SNB’s motivation was indeed a serious “dollar” problem.

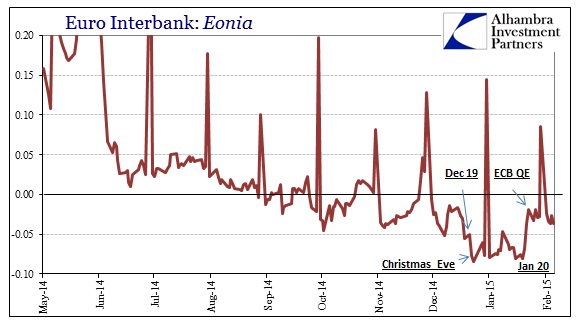

But to really capture any kind of European origin or basis for this illiquidity, there has to at least some kind of spillover or coincident signal. I think that Eonia provides that as a signal for the same kind of fragmentation (increased) as has plagued European banking since this all began back in 2007.

Eonia itself has been persistently negative since the second move by the ECB (September) to drop the rate floor (deposit account) more deeply negative. However, there was a clear and sudden shift starting around December 19, completed on trading of December 24. From that point until January 20, Eonia traded almost exclusively (aside from year end window dressing) at record negative rates.

That simply means, given Eonia’s construction, the biggest European banks were offering more “funding” more to and among themselves, in euros, rather than the rest of the European euro funding market. It is entirely possible, though not very likely, that these big European banks made no adjustment further down the funding “trough” but it stands to reason that they would shift to “less risky” funding positions in the face of growing concerns about less-sizable European financial counterparts. In other words, Eonia seems to indicate a European financial hiccup in euro funding right at the same time “dollar” liquidity was acting strangely.

Given the participation of European banks in the global “dollar” short, again, there isn’t a giant leap to make here that if European banks are taking less risk in euro funding that they would make a parallel move in “dollar” funding.

The question becomes less one of “what” and more of “why.” Was this in relation to Greece? Or the wreckage of European economics before QE? It is impossible to say for sure, but my suspicion is that this was European repositioning ahead of any possible disruption caused by the Greek election. That seems(ed) to be the biggest worry of a potential financial catalyst amongst so many economic deficiencies, and there are a few institutions that probably remember well 2011 (though maybe not enough, since the Greek bond issue last year was far, far oversubscribed).

As you can see in the nominal rate charts above, heavy treasury buying stopped sometime around January 15 (the SNB decision, suggesting again that the removal of the peg was akin to a “dollar” relief among Swiss participation) and January 26 (Greek election that weekend before). In the past few days, really since the beginning of February, treasury rates have retraced some of this buying “panic.” That includes funding markets, as even the eurodollar curve has moved back toward (but not fully either) its mid-December positioning.

Last week’s jobs report had been used to explain the rise in treasury rates, as if the credit markets have suddenly changed their minds about all this bearishness, but I don’t think the two are related at all. In fact, the latest retracing of treasury yields began a few days before the jobs report and the curve remains just as flat as it was when all this began (funding market is even flatter than December 19). In other words, I take these most recent moves as a sort of revelation of the possible “Greek premium” in the credit markets as there seems to be some comfort that “nothing” happened once the election results were revealed.

It is also possible that the ECB’s QE introduction had a calming effect and influence, but that seems to be muted especially in comparison to historical examples of the same kind of introduction. Given the hype and growing unease about Europe in general and Greece in particular, I am leaning more toward the lack of dislocation beyond Greek “markets” the moment the Greek political landscape changed – after all, Greece was assumed the genesis in 2011 memory sprouting “contagion.”

Where this gets complicated is the current mess has yet to find its ultimate conclusion; nothing has been solved by the election. In fact, there is probably more uncertainty now than existed just a few weeks ago, but I think that credit and funding markets (both “dollars” and euros) are simply expressing relief that the election itself did not create disaster, and therefore there is hope for resilience.

Maybe this will inaugurate a “calm” period like what existed between October 15 and the end of November, but there are certain to be more problems ahead. Again, the fact that all these curves are still as flat as they have been is not a sign of total relief, but only specific relief about a specific potential event. Furthermore, that specific relief may not last all that long given the primary fact that Greece’s problems are much deeper than can ever be solved by bailouts or troikas – or even euros.

Beyond even that, if such funding irregularity over just potential specificity can disrupt action so severely as to rock the franc off its “planned” axis, you have to seriously ask just how robust you think these “markets” really are. That has been apparent since at least November 20, 2013, and becomes more so as each of these events or disorderly periods have showed up almost regularly now, spreading all over the world.

Stay In Touch