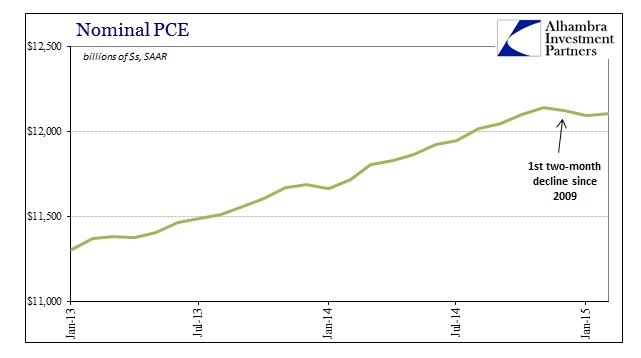

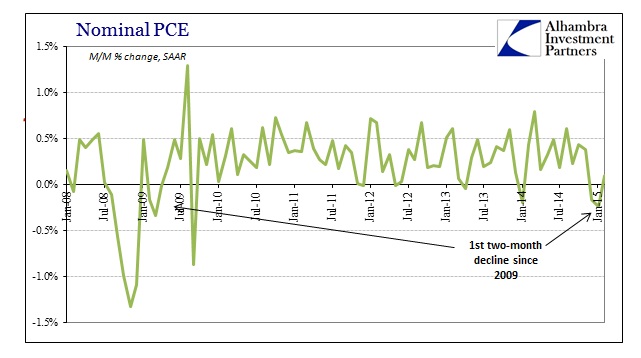

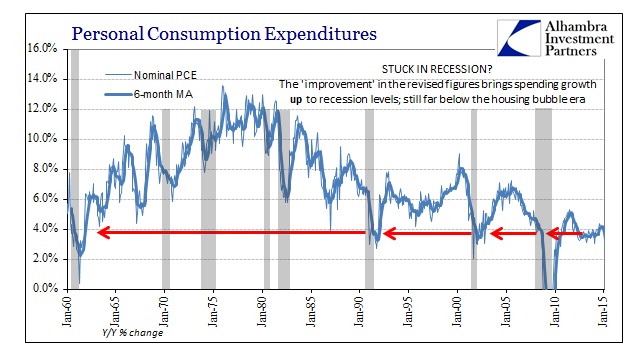

Personal spending had fallen, seasonally-adjusted, for two consecutive months placing warning upon the household sector. The just-released estimates for January show only the smallest of rebounds, just +0.1%, in February suggesting that nothing yet has been resolved in either direction. Unlike last year, there is no surge that would indicate a temporary straying from the otherwise only tepid path.

This unwillingness to engage in spending behavior is confounding mainstream economic sensibility on at least two fronts. First, the reduction in oil prices is thought (wished?) to be a “stimulant” to consumer spending, so the fact there is no transmission here is contradictory. Second, income growth has been much better of late in at least relative comparison to 2013 and early 2014. Thus, any boost in spending was expected to be much greater and more resilient.

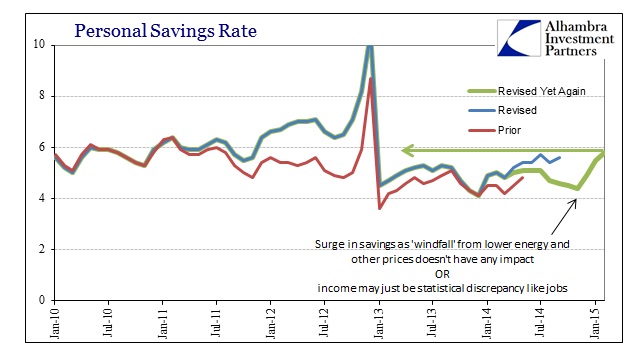

So economists view rising real incomes and thus instead of rising real “demand” and economic activity are delivered a conspicuous spike in the personal savings rate to the highest level (with no actual idea how severely revisions will alter this interpretation) since the 2012 slowdown – which is itself an ominous signal if lower savings have been almost alone driving this minimal economic expansion during the elongated cycle.

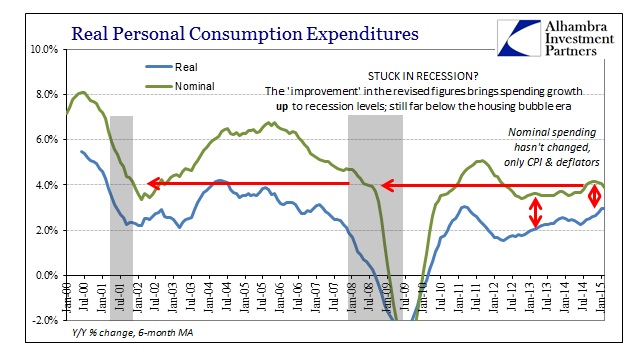

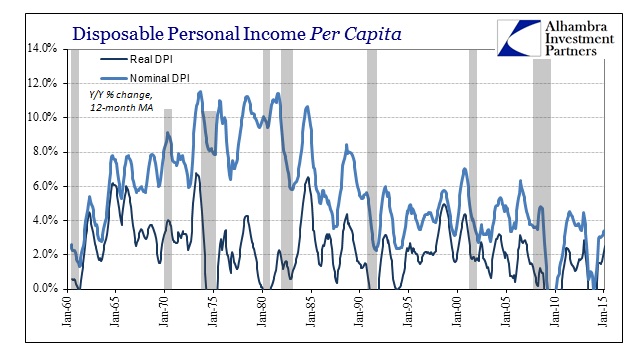

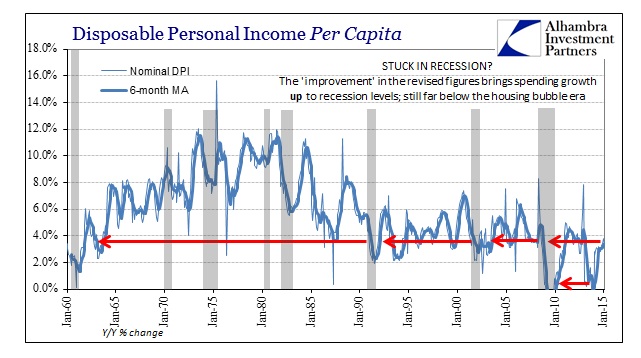

Upon actual review of the data, there are two obvious problems with those expectations for Yellen’s version of economic growth and recovery. The first is the source of the increase in real incomes, namely the singular decline in the calculated inflation rate. In nominal terms, incomes are increasing at much the same decrepit pace as has been the norm since the 2012 slowdown. The only change has been the declining “inflation” rate, accelerated these past few months, which “boosts” only in mathematic terms the appearance of incomes.

Much like Milton Friedman’s permanent income hypothesis, there is no reason to expect that consumers will alter their behavior based on “inflation” alone; especially in the downward direction (since there is no economic vacuum; a low and negative inflation rate usually indicates something very amiss in economic function which may not be visible to economists but would certainly be “felt” by actual economic agents like consumers and businesses). Households respond to not just nominal changes in their paychecks, but those that are judged to be sustainable. People want to get a raise in actual cash, not to see the price of gasoline falling to deliver such “gains” however much that may help take off some of the pressure.

The only period with a similar intersection of trends in income and “inflation” are the late 1990’s (especially 1997-99) when calculated deflators decreased enough to “boost” real incomes more than just nominal expansion. That wasn’t exactly a robust economic period, coinciding with a large slowdown here and abroad during the Asian flu, and then leading into the dot-com bust and recession. Further, both nominal incomes and real incomes were growing much, much faster than anything seen recently. In fact, you can make the judgment that incomes by themselves tell us very little about the state of the economic cycle especially in the period just prior to inflections (there are several cases where an income surge precedes by only months a recession, which isn’t unexpected as businesses that have a major and sharp cost increase may tend to cut back on everything else in response).

The second problem with any expectation of a 2015 boost in spending is this historical context. Incomes now may look better in comparison to last year or the year before, but those are not the appropriate benchmarks. By all historical standards, incomes and spending levels remain stuck at highly deficient rates, which suggests at least somewhat how businesses view their cost structures (and how 2015’s even minor increase in income may actually be unwelcome on the other side of the labor/capital exchange, especially if it hasn’t been met with an offsetting increase in revenue).

Because of these deficiencies, viewed in proper context, the only variables that are changed are the calculated inflation rate (down) and the personal savings rate (up). Actual American households are not experiencing actual cash flow gains, and certainly not in the manner of past “cycles.” In fact, the “biggest payroll expansion in decades” only brought income growth up to a level that used to signal problems, even in the last decade when income growth was already then problematic.

People are not going to go and blow out their paychecks on big spending splurges simply because they save $50 at the gas pump. They know all too well that cash increases have been predictably muted for a long time, and they see no reason for that to change no matter how much the unemployment rate is cited in the mainstream media.

Stay In Touch