If there is actually a tight correlation between jobless claims and the Establishment Survey, as I think there is, then we should expect tomorrow’s payroll report to be totally in-line with recent months. That would be despite all the growing negativity in economic accounts elsewhere, but I think it is more and more apparent that trend-cycle analysis (or guesses) is driving the BLS’s figures. It has been a bedrock assumption since the early days of the transition to stochastic modeling in these data points, and with major difficulties in this “cycle” as compared to any prior it would (in some respects) make sense that trend-cycle would dominate.

In the first place, the BLS does not estimate how many jobs were created in each month, a fact that goes far beyond just seasonal adjustments. They couch the data series in those terms solely for mass consumption of the attempt. The BLS instead tries to model variations in trends, with all sorts of formulas and regressions about what to expect from “regular” volatility. The largest source of volatility in employment, as with almost everything else, remains trend-cycle, but most especially that latter term.

For example, if the trend is determined (after the fact) to have shifted from growth to recession, the BLS will retroactively adjust their variation estimates simply because in recession volatility is expected to be much greater; with heavy emphasis, obviously, on the downside variation. Conversely, if the cycle appears heading in the other direction, the BLS may model greater expectations for upward variation.

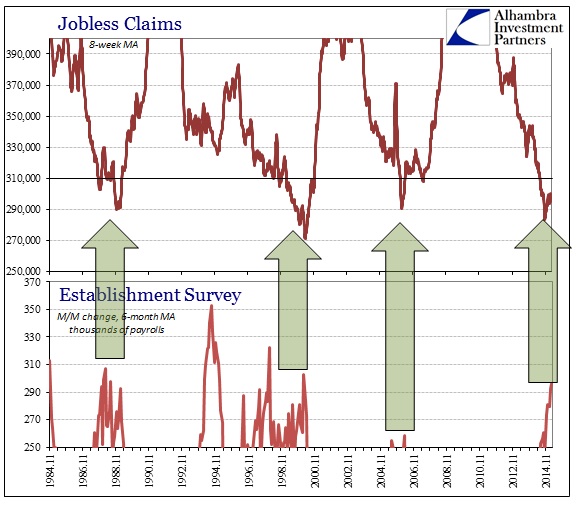

That may (and I stress “may” because the exact formulations and methodology are not open) lead to a sample-modification process whereby on the trigger of some alternate estimate the BLS might amplify upward or downward calculated results. In the current data environment, I don’t think it that difficult to see exactly that process nor the parallel account that may figure in it. Jobless claims are, in historical context, inextricably linked to the Establishment Survey’s variation without any definitive reasons for that. In that respect, I think the BLS uses jobless claims as one measure (probably not alone) of estimating cycle.

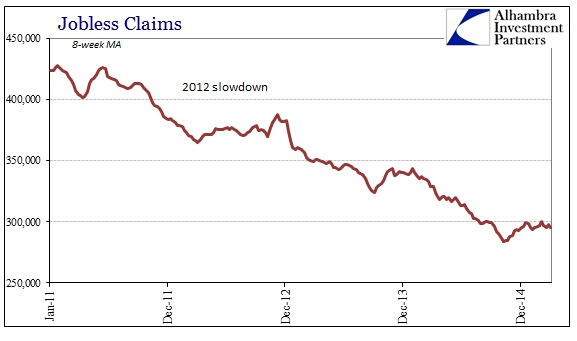

Jobless claims figures for March were slightly better than February, but neither month is seriously outside of recent indications. Judging payrolls solely by jobless claims would tend to suggest a high-growth period that is also highly stable.

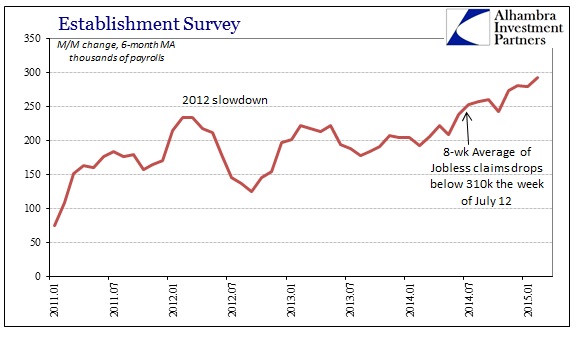

Working backward, I don’t believe it coincidence that the upturn in the Establishment Survey occurred when the moving average of jobless claims fell below either 320k or 310k – somewhere in that vicinity.

In other words, the serious breakout in monthly Establishment Survey gains (highly adjusted for all manner of factors) occurred at around the same time that jobless claims fell to a point that seems to be consistent with prior periods of “full employment” and surging growth. Without knowing exactly what that threshold may be, we can at least surmise either 310k or somewhere around that level and match up what the Establishment Survey estimates were figured at the same times.

I think it is fair to say, with the noted exception of the mid-1990’s, that the link to jobless claims and the Establishment Survey in this manner is evident. In plain English, when jobless claims fell below 320k or 310k in an average, meaning it wasn’t an aberration, the BLS’s methodology interpreted that as an upward shift in cycle – just as it has done at similar points over the past three decades. If trend-cycle analysis forms the better part of estimated variation in the construction of the monthly figures, it would mean that the BLS amplifies the upward variation to mark what it believes is an appropriate shift in cycle.

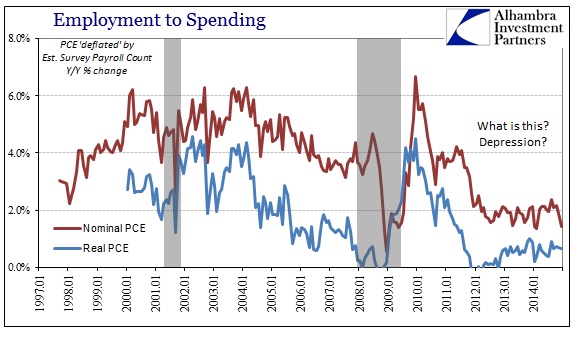

The question then becomes whether or not there remains a solid relationship between jobless claims and cycle. I think that, at the very least, this “recovery” cycle qualifies as challenging that notion in every possible manner. After all, even hiring patterns at major corporations have been seriously altered by heightened over-management of cost structures, which has remained the mantra of smaller and newer businesses that used to provide much of “trend” job growth (and who may no longer exist in numbers as in previous cycles) in the first place. The fact that there are fewer people filing for initial jobless claims is not automatically synonymous with vastly and greatly expanding payrolls – but it is certainly taken that way and I believe the BLS is currently viewing it in exactly that fashion.

That would further explain as to why Janet Yellen and the FOMC are so confused about the economy, as they view the Establishment Survey with all its adjustments and stochastic processes as hardened gospel, unchallenged as to whether past assumptions still apply. Despite the dynamic nature of the real world, after all made more so by the “neutral” efforts of the Greenspan/Bernanke/Yellen complex, orthodox economics exists exclusively upon static assumptions, “laws” and “rules.”

If there is no longer a solidified link between jobless claims and the actual economic cycle, the FOMC and orthodox economists are relying, almost exclusively, upon a false signal. Again, that would expound on their “ability” to see an economy that no one else does, nor certainly not one of majority experience. As the world’s media outlets prepare to tell you exactly how many jobs were created last month, worded against a backdrop of sounding surety, it bears factoring this systemic process.

Stay In Touch