The March FOMC statement that caused a serious inflection in so many places was a reality check upon not monetary policy but economic fluency. In some ways it is subtle by design, but the changes made between the policy statement in January and that in March were more obvious and open. I have to wonder how much the then-surging “dollar” played into considerations about clearly softening policy expectations. Was the FOMC attempting to “boost” funding markets that had begun to seriously degrade?

Even if that were the case, that might still be backwards since I don’t think wholesale “money” is being positioned as much by policy anymore as by economic sufficiency. In other words, the Fed may have attempted to reassure repo and swaps that monetary policy wasn’t quite ready yet to shift toward “tightening” when repo and swaps were more concerned about monetary assessments firming about the actual economy. In that respect, softening economic views may have helped some parts that are more susceptible to QE-type persuasions, but overall bank balance sheet concavity (in the aggregate) may be finally interpreting “correctly” – if the Fed is no longer assured about the recovery, that supersedes a more distant expectation for ending ZIRP or even any noises about QE5.

Some of that relates to the recent weakness, which the FOMC, as noted above, was forced to reckon. In the January statement, they said this:

Information received since the Federal Open Market Committee met in December suggests that economic activity has been expanding at a solid pace.

By March, completely different suggestions about just how sure orthodox and academic economists are of all of this “transitory” nature.

Information received since the Federal Open Market Committee met in January suggests that economic growth has moderated somewhat.

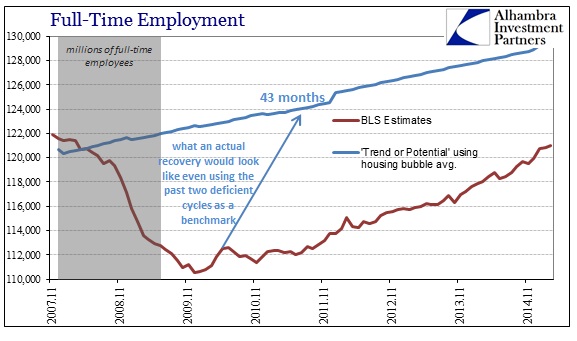

This change was notable not just for that language but also after the January minutes admitted a lack of wage advance that should have accompanied all this Establishment Survey robustness. But perhaps Janet Yellen was more forceful in her March press conference accompanying that “moderated” language, noting, “participants are now seeing more slack in the economy than they previously did.” If there were a launch date for the recovery , which these orthodox economists include “inflation”, it was significantly pushed back by Yellen’s confession.

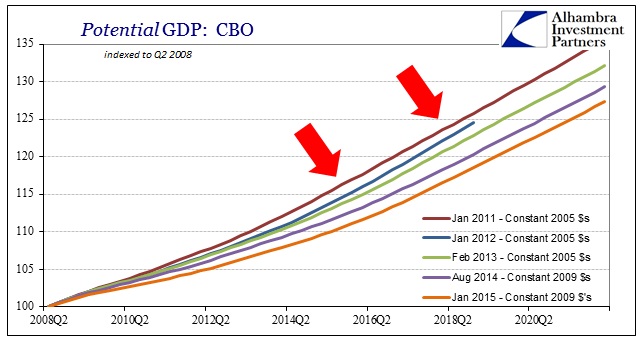

There are a lot of broken promises in all this shifting language, which may be why funding markets are so reticent about jumping back onboard skewed QE and policy intentions. That divergence extends also to more recent “admissions” about the overall state of policy intentions, particularly as they relate to deeper economic context. While the official end of the statement was focusing on the short-term growth considerations (in the wrong direction), the Fed has also been more quietly marking down longer run expectations. It is here that I think the most damage to credibility has been done, and where focus is shifting – though not without letting go of cyclical considerations nearer term.

Again, these are major broken promises that call into question fundamental assumptions about pretty much everything that has existed and happened since late 2007. I seriously doubt that stock investors have so bid up stock prices on the dulled view that the long run economy will be far less ebullient and buoying than even the one that existed, hazardously enough, during the housing bubble portion. Every central banker stated clearly that a full recovery should be expected, unequivocally, as central banks possessed the power to make it so. The effective date of that promise has been altered continually by events and reality, but up until now (or 2013 for some) that has remained the financial basis.

Some comfort has been asserted, though less stridently, that whatever problems in the US would be solved or offset by a return to growth in especially emerging markets and thus the overall global economy. The continued acceptance of that global system as anything other than a unified whole has fostered these dangerously naïve views about what monetary aims could possibly achieve. That is why continued downgrades to even global potential alongside US deficiencies undermine the idea of monetary policy as a solution to anything but shallow emotion.

Potential growth, which gauges how fast economies can grow over time without hitting inflationary speed bumps, already was slowing in richer economies before the financial crisis due to ageing populations and a drop in technological innovation.

But declines in private investment and employment growth cut annual potential growth in these countries to 1.3 percent between 2008 and 2014, half a percentage point lower than before the crisis, according to the IMF study.

A half percent in compounded growth, even classed as “potential”, is utterly enormous and dangerous. The IMF estimates that “potential” will eventually rise to 1.6%, but that remains significantly below pre-crisis existence. Even that view, tempered as it may be only in comparison to the more optimistic versions that still existed more recently, is again in danger as further monetary promises are being unwound.

It also said weak demand in the euro zone and Japan could prompt even lower potential growth than forecast. The study comes ahead of the Fund’s global economic forecasts next week.

In emerging markets, potential annual growth fell to 6.5 percent from 2008 to 2014, about 2 percentage points lower than before the crisis, and is expected to fall further to 5.2 percent over the next five years as populations age, structural constraints curb capital growth, and productivity slows.

The more “stimulus” that has been added to the global economy, the more the global economy’s potential seems to erode; the more attention is paid to boosting “aggregate demand” the less “demand” actually arrives. Orthodox economics places blame for that with the economy itself, as if monetary policy globally is reactive to this reality – but none of those central banks bothered to say so when in the course of hitting and piercing the zero lower bound to begin with. The fact that this is happening globally is surely dispositive about what monetary policy can possibly achieve – very little aside from asset bubbles.

With interest rates low, “monetary policy in advanced economies may again be confronted with the problem of the zero lower bound if adverse growth shocks materialise,” the IMF said.

It is here that I think funding markets are already anticipating. The confluence of short term considerations with longer-term, clear failure means that without serious reform of some kind there won’t be anything different about the future as what we have seen of this “recovery” – except the growing possibility that it can, in fact, get worse. In other words, that would mean very little economic upside with at least intermittent openings for further and sharp economic decay.

In short, Japanification moves forward though nobody in a policymaking setting seems to want so say so – at least not publicly, of course. You would think the media might pick up on this, as this would be the story of all stories, but they are too busy trying to figure out just how much the US economy is “booming” right now if only they could find it.

In my personal opinion, the current FOMC knows they are in serious trouble but absolutely cannot admit as much – as the whole thing would crash right at that moment. I fully believe, as Bernanke has been busy doing this week and last, the FOMC is not really interested in the economy so much as they are in distancing themselves from it, which accounts for this flurry of conspicuously detached admissions. I have said since 2013 that ending QE had nothing to do with the recovery and everything to do with bubbles, and I think we are reaching saturation in that regard. The FOMC “needs” to get some daylight between QE (and even ZIRP if they can manage, but I still don’t think they ever get there) and any recession/bubble crash because this time, unlike 2008, attention is already focused squarely in their direction. They desire plausible deniability, though I don’t think this time they can get away with it (certainly not so easily).

The point of funding markets is that Japanification isn’t an accident and that both long- and short-term economic problems are as much a problem for the current state of monetarism. Bernanke has already downplayed the Fed’s ability, and the FOMC and IMF are doing the same thing by suggesting “potential” as the proximate cause. If the global economy is to live down to these diminished expectations, and what a disaster that would be, it is not some exogenous failure of human nature or organic economic arrangements, it is clearly those that feel the need and power to do the arranging all their own. The more they attempt, the less there is of a response; an elegant simplicity that I think will mark the next crisis cycle if it hasn’t already begun at the contours.

Stay In Touch