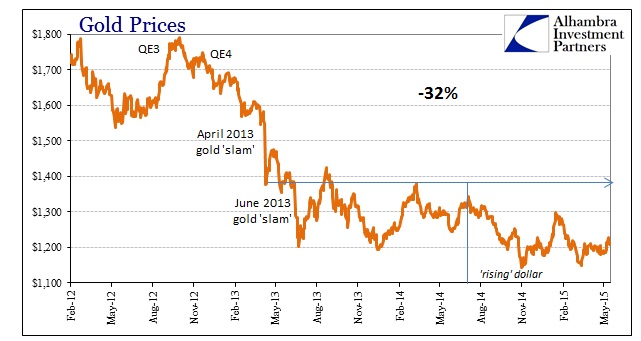

A little over two years ago, in the middle of April 2013, there was a gold crash that came seemingly out of nowhere. Worse, for gold investors anyway, that crash was repeated just a few months later. Where gold had stood just shy of $1,800 an ounce at the start of QE3, those cascades had brought the metal price down to just $1,200. For many, especially orthodox economists, it heralded the end of the “fear trade” and meant, unambiguously, that the recovery had finally at long last arrived.

As Felix Salmon wrote at Reuters in an article titled, The Fear Bubble Bursts:

As a result, the falling price of gold is more important than simply being an opportunity for schadenfreude around the likes of Glenn Beck or John Paulson or Zero Hedge…

The biggest problem in the markets right now is that they’re still far too risk-averse. Fear-based assets like gold, Treasury bonds, and cash are in high demand, while there isn’t enough money flowing through greed-based assets like stocks and bank loans and into the economy as a whole. Even if the stock market is expensive, the number of primary and secondary offerings remains low; similarly, banks are not expanding their loan books nearly fast enough…

My hope is that the price of gold will continue to fall, that goldbugs will look increasingly silly, and that as a result Americans with savings will conclude that the best thing to do with those savings is to put them to work in a productive manner, rather than self-defeatingly trying to protect what they have.

Gold has not continued that wished-for collapse, but hasn’t risen much either. In fact, the price of gold remained above $1,300 for only short periods and hasn’t been near that level outside of the January 2015 “Swiss problem.” Most gold analysis views it in terms of not just the “fear bubble” but also a proxy for interest rates and monetary policy. There is already a problem with that latter interpretation, as the price of gold began to its decline almost the moment QE3 started. Economists think of gold investors in only these terms, as emotional and irrational Fed-haters.

In the broader economic context, then, the fact that gold was falling at the same time QE’s had commenced provided that hoped-for economic confirmation. Gold adherents were getting their “debasement” but that gold prices were sharply reacting in the “wrong” direction which could only mean, to the mainline economic view, that QE wasn’t just debasing the dollar it was actually working while doing so.

Writing just prior to the second gold “slam” in June 2013, Nouriel Roubini took his best shots at framing gold’s descent as a victory for Ben Bernanke:

Third, unlike other assets, gold does not provide any income. Whereas equities have dividends, bonds have coupons, and homes provide rents, gold is solely a play on capital appreciation. Now that the global economy is recovering, other assets—equities or even revived real estate—thus provide higher returns. Indeed, U.S. and global equities have vastly outperformed gold since the sharp rise in gold prices in early 2009.

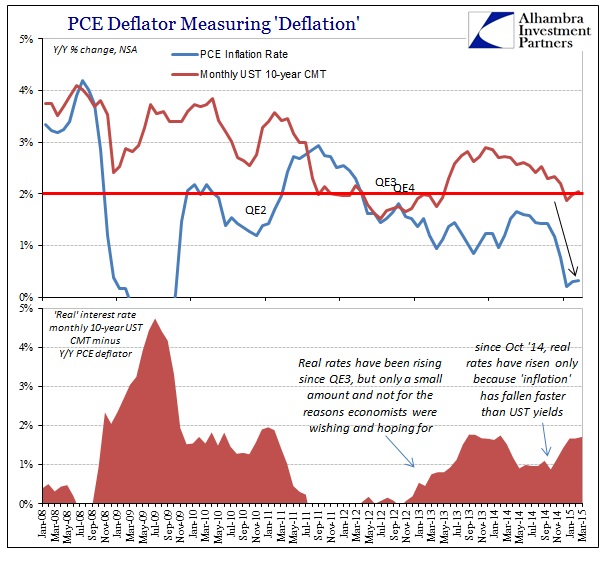

Fourth, gold prices rose sharply when real (inflation-adjusted) interest rates became increasingly negative after successive rounds of quantitative easing. The time to buy gold is when the real returns on cash and bonds are negative and falling. But the more positive outlook about the U.S. and the global economy implies that over time the Federal Reserve and other central banks will exit from quantitative easing and zero policy rates, which means that real rates will rise, rather than fall. [emphasis added]

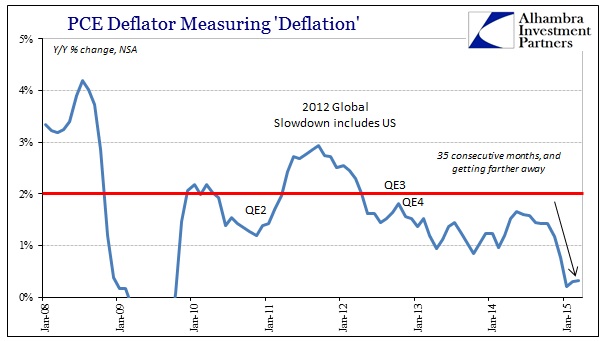

Roubini’s fourth point may be the most important, as it implies that there is a relationship between the Fed’s policies, especially QE’s, and the rate of inflation. However, recent history, especially in the two years since gold crashed, has proven that totally and fully incorrect. There has been no “inflation” much at all, and even to the point that the Fed’s preferred inflation target, the PCE deflator, has come in under the policy target of 2% for 35 straight months dating back to just before QE3 was rumored.

If QE3 and QE4 had any impact on “inflation” or recovery in the US it is not apparent. For a time in 2013, Roubini’s “rising real rate” scenario seemed to be somewhat plausible as the entire UST complex and yield curve shifted upward. While the PCE deflator did not much move, that temporary rise in nominal yields brought real rates up and appeared at first as if it might reflect at least the near-future possibility of the recovery and recovery financial dynamics.

But that all turned around in October and November 2013. In other words, anything resembling the recovery in these financial terms had a very short life. By November 2013, nominal yields had slowed their ascent and the overall UST yield curve turned durably bearish. Though real rates fell once more in the middle of 2014 as “inflation” ticked up slightly, since October 2014 “inflation” has declined far faster than nominal yields. So real interest rates have been rising, but not for the reasons outlined by Roubini and his orthodox notions of recovery.

Clearly, there is “something” missing here beyond just the recovery economists were so sure that gold’s crash was foretelling. Normalizing both economic and financial conditions would mean interest rates rising back toward where they were pre-crisis just as “inflation” picks up and remains at or slightly above 2%. Neither of those factors is evident anywhere at all in the two years since gold prices crashed.

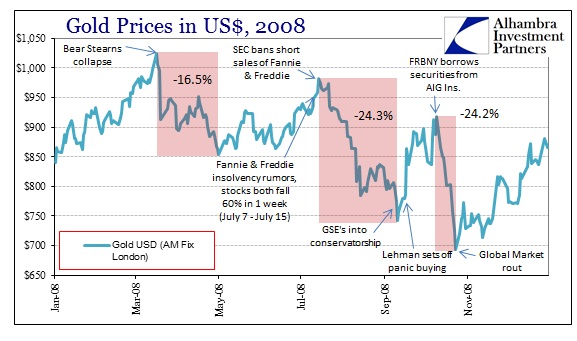

The idea of gold prices behaving like a zero-coupon bond is in some ways relevant to this problem. Economists only think of the asset side of that paradigm while never moving beyond that into liabilities. A government bond is an asset, sure enough, but it can also be part of the liability structure in repo. Just as government bonds act as collateral, so too does gold. That has led to strict and lasting misinterpretation about the behavior of gold in 2008, which Roubini tried to incorporate within his anti-gold stance.

But, even in that dire scenario, gold might be a poor investment. Indeed, at the peak of the global financial crisis in 2008 and 2009, gold prices fell sharply a few times. In an extreme credit crunch, leveraged purchases of gold cause forced sales, because any price correction triggers margin calls.

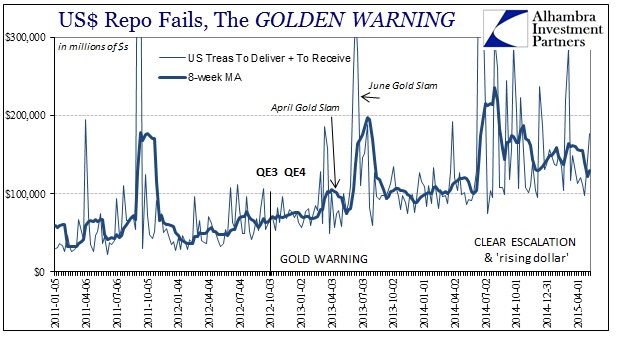

That isn’t what happened to gold, at all. You can disprove that theory rather easily, as I wrote contemporarily in April 2013 about the gold slam as it was occurring.

Gold prices crashed on three separate occasions in 2008, all of which were tied to problems in collateral chains and interbank financial irregularities. In the first episode, the price decline started when Bear Stearns failed and ended on May 2, 2008. That date stands out because that was the first time the Fed had expanded its list of acceptable and eligible collateral in its TSLF Schedule 2 to include non-GSE MBS paper as well as strictly non-mortgage ABS. In other words, the collateral implosion started by Bear Stearns “cold fusion” ended the moment the Fed debased not the currency or bank reserves but the list of “appropriate” interbank collateral.

As I described it in April 2013:

That means in times of extreme stress, gold acts like a universal liquidity stopgap – when all else fails, repo gold. The operational reality of a gold repo is a gold lease, charged at the forward rate (GOFO). In terms of market mechanics, a dramatic increase in gold leasing is seen as a massive increase in supply on the paper markets.

For various reasons in the past five years, collateral chains and the available collateral pool has dwindled dramatically. That has left banks to scramble for operational bypasses, but it also has led to periods of very acute stress. [emphasis in original]

As a representation of the “dollar”, then, gold prices act as a partial proxy of actual “dollar” availability balanced against that or any desperate bid for safety – and having very little to do with interest rate differentials.

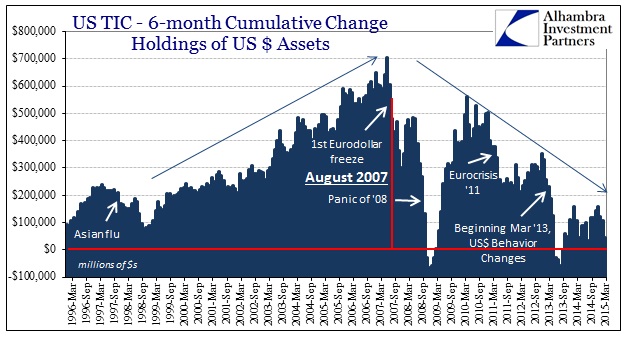

That makes the trend in gold since QE3 started all the more interesting if we take in the “correct” context of the global “dollar.” Clearly, we cannot take falling gold as indicating a recovery because one never came and it surely looks to be further away now than then, an interpretation consistent with financial measures, yields and prices. But we can look at gold over the past three years since QE3 and link its behavior to that of the “dollar.”

While economists might still see QE as contributing to global “liquidity”, which it seems like it should what with all those trillions in bank “reserves” created, there has been persistent criticism of it as nurturing instead the opposite condition. The major part of creating all those bank “reserves” is to remove collateral in the process – transforming a repo-based system back toward a more-traditional idea of how banking used to work. But the wholesale system since August 2007 has been moving away from unsecured lending interbank and otherwise to almost purely repo.

The Fed has been very aware of this problem especially when it nearly destroyed repo in April 2011 (and then a desperate “dollar” problem only two months later?) by stripping the system of almost all t-bills toward the end of QE2 (which was the reason for Operation Twist). When planning and extrapolating for QE3, those operational constraints were at best secondary to the psychological effects that were supposed to accompany Bernanke’s massive and “open ended” monetary program. Getting everyone to “feel” better that the Fed was doing something big was meant as a far greater economic stimulant than the negative liquidity of depriving usable collateral in terrible quantities. The recovery from the defeat of pessimism, in Felix Salmon’s terms, was thought to be so much more powerful than the status of actual “dollar” circulation ability.

So much happy emotion was never really much of a “stimulant”, of course, but the negative factors on “dollar” circulation were very real. In many ways, the collapse in gold presaged this latest stage or leg in the collapse of the global “dollar”, eurodollars in particular, which starts to account for the economic behavior these past few years as well. Gold, then, since early 2008 has been telling us a lot about the tendency of the eurodollar standard toward outright imbalance and dysfunction. That is a condition that is not in any way conducive for a global recovery, which is one big reason why, despite orthodox giddiness over gold prices, it never came.

It also suggests that QE has acted as a depressant upon the global economy, net, depriving significant circulation ability in eurodollar channels and beyond. This would include not just reduced levels of collateral flow, but also bank balance sheet capacity overall in the full 2013 aftermath of QE3 and QE4. It would have been nice if gold’s price collapse was a signal of actual success, but instead it appears to be just another form of structural financial decay and the economic malaise (at best) that attends it. In that view, it is somewhat amazing that gold prices haven’t suffered further lower lows, which suggests that there may actually have been a significant safety bid all along. The “fear” bubble did not end; it was overwhelmed by QE’s depressive constant and the related countdown to the end of the eurodollar standard.

Gold price activity since QE3 has been a warning, and a big one, not cause for victory celebrations.

Stay In Touch