The home market may literally be testing the notion that interest rate manipulation has the net effect of pulling forward demand. Existing home sales, as tabulated by the National Association of Realtors, surged in May to a new six-year high. That sounds like terrific news about a rebound in the real estate market after quite a rough period dating back to the middle of 2013, but even the usual monetarism-always-works places are sounding cautious. In this case, with the Fed having spent months and months talking about rate increases, many economists are actually worried that May’s jump in home sales was the last before such conventional outlooks become reality.

The average 30-year fixed mortgage has moved back toward and even above 4% again, which “threatens” to derail what is thought to be a sustainable gain in housing overall.

After renting a two-bedroom unit for four years at the Nineteen North Apartments on Route 19 in McCandless, Andy and Sarah Hadad decided the time had come to invest in a home where they could raise their 3-year-old daughter and build equity for their future.

Another deciding factor? The couple began to see mortgage rates moving higher. They breathed a sigh of relief when their lender was able to lock the interest rate on their 30-year mortgage at 4 percent.

“We know we will probably never see interest rates like this again,” said Mr. Hadad, 28, a quality assurance engineer for a software company in Seven Fields.

It seems more than a little assaultive on common sense where a minor uptick in interest rates would cluster so much activity. But the 4% threshold, being a round number, has triggered inordinate commentary and even a little nervousness about the severity of any negative feedback from higher rates despite commentary taking great pains to promise that rates will rise but only gently; as if economists are trying to reassure instead themselves after surveying the great imbalances.

For five years, mortgage rates have hovered around 50-year lows, a situation most economists believe will start to reverse if the Federal Reserve begins to raise interest rates later this year. Rates on 30-year conventional mortgages averaged 4% for the week ended Thursday, according to mortgage giant Freddie Mac. Until a few weeks ago, mortgage rates had been below 4% since November…

But higher rates could spell trouble for pricier West Coast cities, such as San Francisco, Los Angeles and San Diego, where home prices are already out of reach of many residents and would only be made worse if mortgage rates rise.

In Los Angeles, for example, with mortgage rates at 4%, a typical household would have to spend 41% of its income on mortgage payments to buy a house for the median price in the area, according to Zillow. If rates rise to 5%, that household would need to spend 46% of its income to afford mortgage payments.

That description sounds precariously similar to a bubble – where all but the interest rate lends toward “unaffordable.” Each and every mainstream treatment of the rate “conundrum”, however, is also quite careful about its ultimate reassurance regardless of any interest rate movements; growing income and plentiful jobs are simply expected to offset any negative pressure from interest rate “normalization.”

It is indecently odd in how a nearly historically low interest rate at 4% could trigger such separation anxiety. Is 4.5% all that different than 3.5%? In actual context, the relation between the two rates is entirely miniscule, or at least should be. These are not normal times, however, and there is more than a little evidence that this rate distortion, intended by QE’s, has cratered actual economic fundamental pertaining to housing; thus the nervousness.

Orthodox economics is neither unaware of the imbalance nor insensitive to its dangers; it only minimizes the probability of such negativity becoming a purely detached reality. The FOMC does not expect that rising interest rates will exhibit only that negative pressure, rather it intends such negative pressures to be more than negated and offset by the rising economy the negative pressures had great hand in creating. So it is ingrained ritual where worries about rising rates on an imbalanced, even subtly bubbly, housing market is dispelled by the magic of monetaristic theory.

If the theory is correct, then the housing market sails along without pause or interruption because wages rise with house prices and payment costs due to interest rate normalization. In that respect, the whole bubble or imbalance is nothing but the cost of restarting the economy. This is hysteresis.

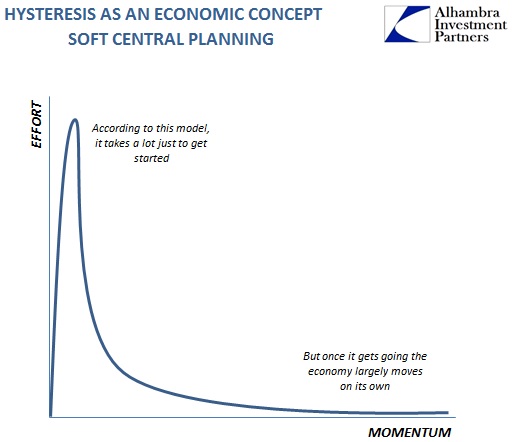

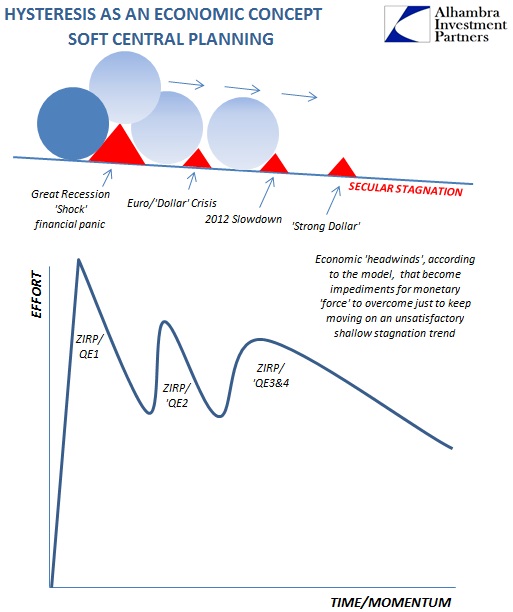

The dominant view of any business cycle is where a “shock” disrupts the economic trajectory off its path close to or at “potential.” In order to return to trend monetary and/or fiscal stimulus is “required” to give the economy something of a push or jump-start. The reason is that orthodox economics does not view the economy as able to reset its own course, as there is supposedly grave danger in not interrupting any recessionary trend via government action. Further, recessions are treated as having no positive attributes, even creative destruction, which leads to the hardened view that monetarism must everywhere and anywhere fight contraction.

From this view, it follows that the initial stages of “stimulus” have to be much larger than anything thereafter. It is believed that to overcome the shock stimulus must be exceedingly large to gain initial momentum; once momentum is achieved, the economy moving back toward trend, little actual effort is required to sustain forward progress.

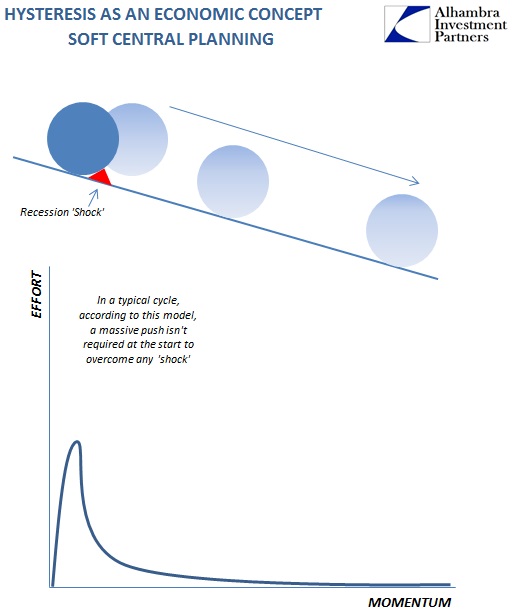

Like a ball rolling down an incline, stopped by an impediment along the way, hysteresis suggests that stimulus is only necessary to get over the hump. Once that hurdle is cleared, the natural, downward incline of the slope (economic potential) takes over and stimulus can be wound down. Again, it does not matter in this view if “stimulus” amounts to negative pressures of arbitrary redistribution, like housing as we see it, because once the blockage is overcome momentum cures and overcomes all objections and what would normally be objectionable activity.

Relating this to our own experience in the “recovery” period challenges the notions underpinning this view, but it also answers as to why there is never any attempt toward baseline reassessment. In short, there are any number of excuses built into the model which offer plausible calculation problems alone.

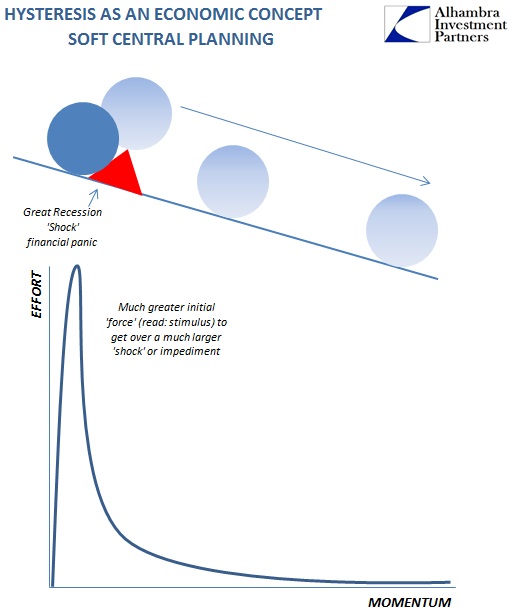

The first is the size of the “shock” itself. If you intend on getting a boulder moving down a hill, it matters greatly how big a push you assert at the outset; not enough force and the boulder goes nowhere. That was the first admonishment about the lack of recovery after the Great Recession. Monetarists and Keynesians (redundant) alike were quick to point out a few years after (always after; where are the precise calculations before?) that the ARRA “stimulus” should have been bigger. Even at more than $800 billion, it was ex post facto deemed insufficient because of hysteresis, meaning the GR obstruction was larger than even an $800 billion force could overcome; to a lesser extent QE1 and ZIRP fell into the same category.

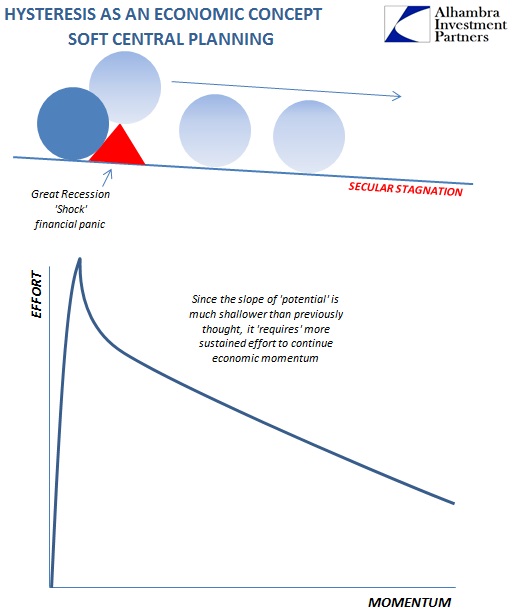

The second great problem is the slope itself. If you give the same boulder an enormous initial shove but the incline is quite shallow, perhaps even nearly flat, it will not go very far on its own after the initial force application. On such shallow ground, hysteresis is extended whereby the force “required” diminishes much, much slower into momentum; translating into more and continuous effort.

In this case, orthodox economics has turned toward “secular stagnation” as akin to a shallow incline (diminished potential). That is why ZIRP has been “necessary” continuously for six and a half years along with four discrete applications of QE in places. Monetarism is still quite powerful, as they see it, but that something is very wrong with the “economy” such that what used to be a steep and easy slope to navigate has so flattened out as to thwart such great and powerful artificiality (like the initial push, it is never answered as to why said slope is never calculated as difficult from the outset, only being revealed afterward).

Yet, even that view is insufficient to describe, in theoretical terms, the events of the “recovery.” In actuality, we have the combination of greater-than-calculated “shock” in the Great Recession followed or amplified (depending on your brand) by secular stagnation, but also a few smaller impediments along the way that have brought the economy to nearly full stop intermittently – thus the four QE’s.

In this view, momentum becomes synonymous with time so that monetary effort is only “buying time” in order that each impediment or mini-shock might be overcome and the economy then roaming freely down even a slight incline. Each of these, according to this view, has the effect of nearly halting economic progress and thus requiring re-addressing through still more monetary redistribution. The overriding theme is neutrality, as all these negative effects to be overcome supposedly have nothing to do with monetarism itself and everything to do with perceived deficiencies in the economy. From this view, monetary policy is never wrong in theory only in application via the measurement problem (which should be disqualifying itself, but ends up as cover since its proponents can claim they updated their models and can make better calculations next time).

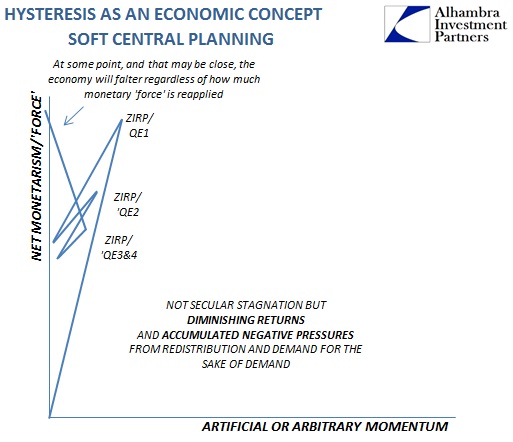

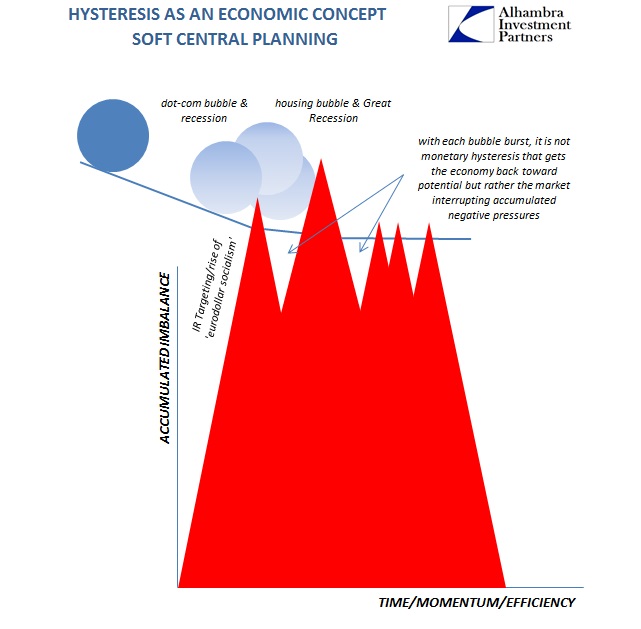

This constant problem of finding new and novel ways to undermine prior calculations (in order to save the theory/ideology) gives away the game. A much simpler and more intuitive explanation, as well as matching actual observations, is one where “momentum” is not quite the correct term for what monetarism actually achieves. Using negative pressures, such as redistribution, what monetary policies “forces” into the economy is not momentum at all but rather a singular or distinct kind that easily wears off not even with the monetary application itself but rather in quite short order. “They” get nothing more than a minor bump in the economy and then leave behind all the problems that went with creating it.

The problem of secular stagnation is the lack of balance sheet in this orthodox view – that negative pressures, like artificial bursts of debt, do not dissipate with their attendant artificial momentum. Instead, these negative pressures do indeed accumulate such that great imbalances end up actually defining progress and even “potential.” This is the great and increasing inefficiency we see with each in the series of serial bubbles.

Worse, however, is that the accumulations become the very reason that “potential” is so disrupted in the first place. There is not some unexplainable “thing” wrong with the economy itself so much as it cannot ignore financial imbalances especially with increasing age and experience. Some of this is easy to see quite tangibly, as households have been reluctant to borrow as they had in the first and especially second bubble periods, but other distortions are much more nefarious and combine toward deeper and more corrosive destruction of the economic interior (stock repurchases instead of productive investment; marginal labor tending toward house-flipping or day-trading rather than productive entrepreneurialism; Ivy League mathematicians and an army of lawyers being trained for Wall Street rather than the next “big thing”). All conspire to “bend” the slope in the wrong direction, making even organic growth that much more difficult.

Monetary neutrality demands that nothing accumulates, and so orthodox economics can proceed without a balance sheet view since everything is reduced to simple transactions in the most generic terms. The FOMC can completely disrupt the quite natural and healthy balance in the depressed housing market because they think in the end everything works out as a net positive over time. This was and remains, essentially, Ben Bernanke’s ethos – yes, the FOMC was taking money from seniors and responsible savers and that was a direct “cost” but it will be worth it when the entire economy runs back to potential and everyone “wins.” In other words, it is actually an intention of monetary policy that only a few “win” now because over time we all are supposed do.

That view would be much more plausible if it could actually calculate the “correct” forces before they are unleashed; where was secular stagnation in 2009? How about 1999? Or hysteresis, for that matter? These are applied only afterward because monetary neutrality supersedes everything, which means there can be no such disqualifying observation or falsifiable conclusion only supposedly better models of the same thing.

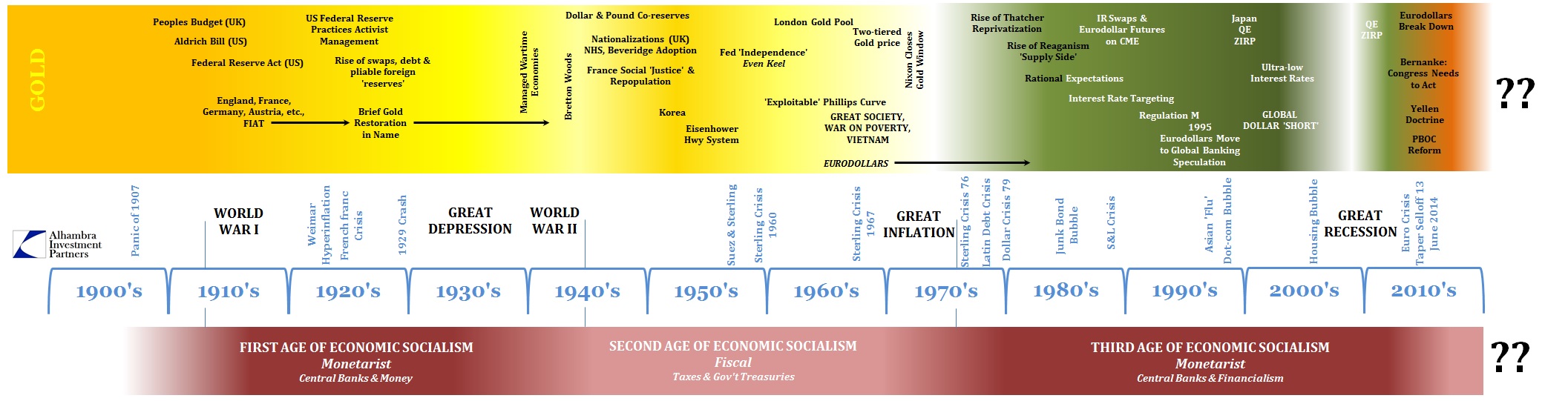

Hysteresis, like secular stagnation gaining usability in the past few years, is actually a concept appropriated from the physical world adjusted to economics as it sees itself a hard discipline. That this is not well-adapted for an economy isn’t really a mystery, as a true economy is far more a living, breathing entity than some machine. That is why I think the Animal Farm analogy I used last week fits so well. All orthodox economics reduces individuals to cogs to be exploited, rendered by financial and monetary force “for your own good.” It is perfectly consistent with the continued ages of socialist monetary and economic planning as it provides both necessary components to top-down control: complexity passing for objectivity and ready pretexts for maintaining the paradigm when it inevitably fails to match reduced projections, let alone promised efficacy.

Stay In Touch