On November 9, the OECD issued its twice-yearly Economic Outlook statbook, updated for projections into Q3 for most national economic accounts. Despite past enthusiasm for global prospects in 2015, the narrative has not-so-subtly shifted, a major transformation coming from an orthodox bastion like the OECD.

Global growth prospects have clouded this year. Global growth has eased to around 3%, well below its long-run average. This largely reflects further weakness in emerging market economies (EMEs). Deep recessions have emerged in Brazil and Russia, whilst the ongoing slowdown in China and the associated weakness of commodity prices has hit activity in key trading partners and commodity exporting economies, and increased financial market uncertainty.

Global trade growth has slowed markedly, especially in the EMEs, and financial conditions have become less supportive in most economies.

It is difficult to simply accept these limitations lacking comprehensive causative processes put forth, but the fact that they are at least being recognized represents a (small) step forward. These are portrayed as if they are “things” of themselves; commodity price collapse, “financial market uncertainty”, global trade growth collapse, etc. Despite the unexamined “mystery” of all those, or maybe because of that intentional obtuseness, the OECD still expects global growth to accelerate in 2016 and really 2017. That is, of course, the same pattern that plays out year after year after year, only 2015 has already held more than the typical amount of setbacks and “unconnected” financial mysteriousness.

To this point, the organization is unwilling to see anything more than a visible economic problem for EM’s alone. Brazil and Russia have their recessions, and China its unexplained slowdown, but the rest of the “developed” world is expected to remain rather steady in growth (well, except Canada perhaps?) no matter all the global turmoil. It is the stated “risks”, however, that suggest much about the inner turmoil at these economic outposts:

Growth would also be hit in the euro area, as well as Japan, where the short-run impact of past stimulus has proved weaker than anticipated and uncertainty remains about future policy choices.

There are increasing signs that the anticipated path of potential output may fail to materialise in many economies, requiring a reassessment of monetary and fiscal policy strategies.

So while the OECD isn’t quite ready to throw in the towel globally, they are, significantly, at least contemplating how much of their baseline is already wrong and inapplicable. This is a marked and remarkable shift from the OECD position from just before the “dollar’s” mid-2014 turn. From the May 2014 version:

On the other hand, the pace of growth in the major emerging market economies has slowed. Part of this deceleration is benign, reflecting cyclical slowdowns from overheated starting positions – the growth rates now seen in China are undoubtedly more sustainable from both economic and environmental perspectives than the double-digit pace of a few years ago. However, managing the credit slowdown and the risk that built up during the period of easy global monetary conditions could be a major challenge.

The likelihood of some of the most worrisome events that have preoccupied markets and policymakers in recent years has diminished. Risks are overall better balanced although still tiled to the downside. Financial tensions in emerging markets are one risk that could blow the global recovery off course and have bigger spillovers than anticipated It is not the only one. Falling inflation in the euro area could turn into deflation. Geopolitical risks have also increased since the start of the year.

Despite suggesting those “risks” to the global economic forecast, and thus providing again recognition that even the OECD saw the unifying financial or monetary element, the “dollar”, as early as then, they went on, as always, to just dismiss them in their projections.

Global growth and trade are projected to strengthen at a moderate pace through 2014 and 2015.

Activity in the OECD economies will be boosted by accommodative monetary policies, supportive financial conditions and a fading drag from fiscal consolidation

Growth in many of the large emerging market economies (EMEs) is expected to remain modest relative to past norms, with tighter financial and credit conditions and past policy tightening taking effect and supply-side constraints also damping potential ouput.

And worst of all, the usual orthodox nonsense and buzzwords:

Normal demand-side accelerator-type mechanisms, healthier corporate balance sheets and reduced uncertainty should help business investment to strengthen gradually, and thereby push up trade intensity.

Needless to say, there is far too much of financial and economic nightmare in 2015 to be so complacent about not just 2017 but just the rest of this year – Canada, Brazil and Japan already fraying the ragged edges of even the latest outlook. That also includes the US as it has almost assuredly fallen into a manufacturing recession already. From this, we are supposed to ignore just how well that fits within this damning global economic context. The only way to project gradual global recovery is if the US manufacturing recession is a “thing” all its own, unrelated to any of the innumerable other “things” that have shown up this year; commodity price collapse, “financial market uncertainty”, global trade growth collapse, etc.

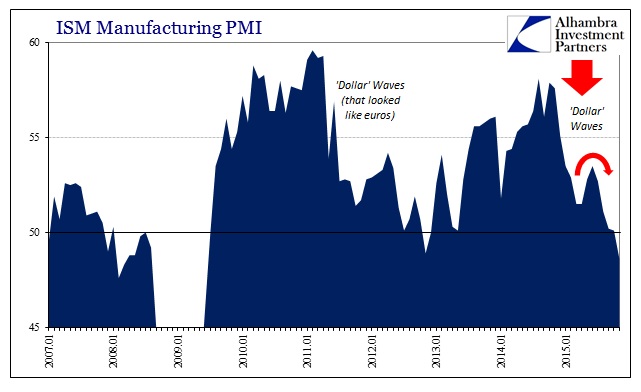

Recent manufacturing readings for the US have only confirmed the recessionary presence, meaning it is left to individual subjectivity as to how to place it within meaningful context.

The U.S. manufacturing sector contracted in November, falling to its worst levels since June 2009, when the economy was still in the midst of a recession, according to an industry report released on Tuesday.

The Institute for Supply Management (ISM) said its index of national factory activity fell to 48.6, the first time the index has been below 50 since November 2012, after reading 50.1 in October. The reading was for expectations of 50.5, according to a Reuters poll of 77 economists.

And how does CNBC provide said meaning?

Frugal consumers are also holding back growth.

From the OECD’s perspective, these were all just “risks” in 2014 and downplayed at that. Now that they are no longer risks but reality, and much worse reality than when even contemplated as risk, they are still treated as just risks? Such confusion stems from the anti-scientific process at the heart of economics. The discipline starts with a predetermined endpoint and then works backwards to fill in commentary and meaning. In other words, Janet Yellen says the economy will be terrific next year (after saying the same last year) and that is the defining quality for everything from there to now. Anything that gets in the way of reaching that future goalpost is “transitory” or an anomaly – no matter how regular these aberrations have become.

In fact, they are everywhere all over the globe and demonstrate what should be a quite alarming coincidence and even coordination. How is it that the US PPI would so closely track the Chinese version if everything contained within each are nothing more than isolated variances of no particular concern, especially in the global context? If nothing else, it is just blind common sense that would realize even generically the desperate coincidence of so many financial irregularities this year as the global economy, and especially global trade, follows them. Again, these are no longer just risks.

The resistance to such an awakening is understandable if still lamentable. If recession is truly the looming assurance, as it increasingly appears, that would mean not just the end of the recovery but the end of “accommodation” as a given force. In other words, Janet Yellen and the OECD start backwards from their endpoint because of their unshakable faith in monetarism, a faith that actually defines how they think an economy does work (and how they produce the core assumptions in their models); should that path from here to there completely unravel, so, too, does their assumed power and philosophy. So they and the media look upon what has already unraveled and claim instead that it has not; the recovery remains intact even though it has ended in a larger and larger portion of the world, including the US.

Stay In Touch