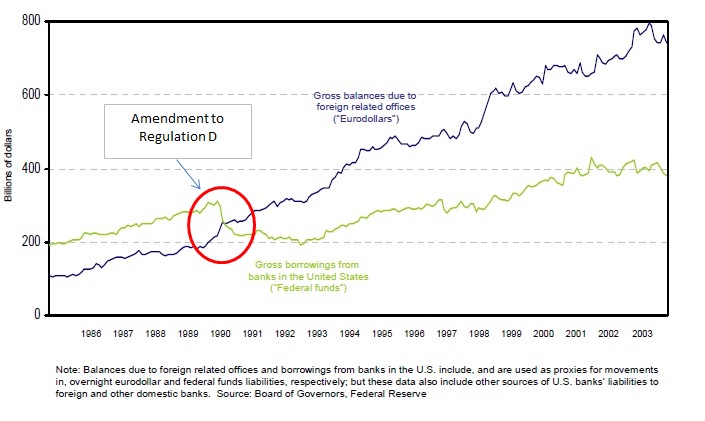

On December 27, 1990, changes to Regulation D went into effect with the maintenance period that began that day. Among those alterations was a reduction in the reserve requirement imposed upon what are officially called “eurocurrency liabilities.” Under the Monetary Control Act of 1980, which made reserve requirements universal to any US chartered federally insured depositories and all its qualified subsidiaries (including Edge Corps and IBF’s), the reserve statute was set at 3% on eurocurrency liabilities. Starting with the maintenance period of December 13, 1990, the ratio fell to 1.5% before being eliminated in the next one.

The change does immediately appear to be substantial let alone profound, but it was perhaps more qualitatively than anything else. It registered eurocurrency, really eurodollars, as perfectly convertible with US bank operations. The rationale for the alterations in Regulation D, including the Monetary Control Act, has little to do with liquidity as you might expect and everything to do with monetary policy of the Federal Reserve. Even though reserve requirements had been a statutory feature dating back to 1863, starting in the 1930’s the element of required reserves shifted more to centralized positions on policy effects and abilities.

As the monetary system underwent radical changes in the late 1950’s and 1960’s, the Fed was forced to try to catch up. Its argument in favor of the 1980 legislation was the clear “movement” of bank liabilities outside its jurisdiction (into eurocurrency markets). A universal regulatory scheme surrounding reserve requirements was believed necessary for greater policy control over domestic monetary aggregates. This argument didn’t last long, as instead the Fed opted at some point in the latter half of the 1980’s for interest rate targeting in the further mistaken belief that by controlling the federal funds rate it would then supersede all other efforts and directly affect any and all monetary aggregates.

The decision to remove the reserve requirement on eurodollar liabilities at the end of 1990 was final acknowledgement of the takeover of interest rate targeting. There was an immediate shift despite what appeared a minor alteration, one again that the Fed did not anticipate (and really, studiously endeavored not to understand).

There were many other predicate developments that “made” the eurodollar system as a complete facility for global financial translation, the introduction of standardized, traded (Chicago) interest rate swaps and eurodollar futures in 1985 as primary examples, but in my view this was perhaps one of the most significant evolutionary steps in delivering the fully mature eurodollar system. By making them fully convertible, the Fed was again expecting to control any and all monetary contributions via interest rate targeting; from the perspective of banking, it was an entirely different set of circumstances as it allowed free and liquid flow across all boundaries. With those qualitative hurdles now overcome, the advancements in the early to middle 1990’s (VaR, Basel leading to math-as-money) added the quantitative elements that we find as dramatic expansion into the serial asset bubbles.

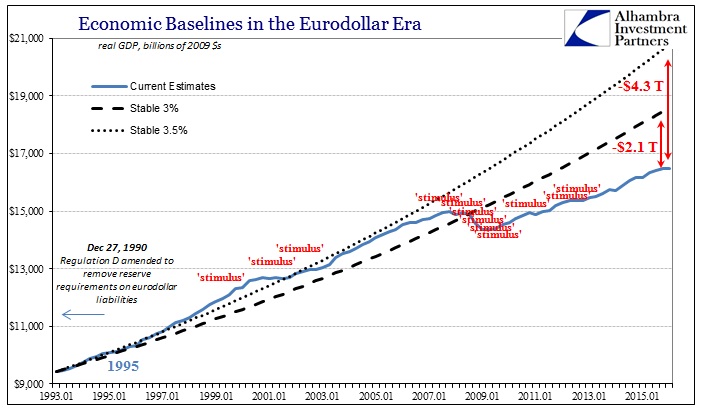

Unfortunately, economists and policymakers today remain mostly uninterested in this monetary history even though they have every reason to seek it out. The most intense and pressing of those justifications is this rotten economic circumstance itself, an obviously depressed condition that lingers and only gets worse no matter what “stimulus” is applied. Rather than tackle the clear objections as nothing seems to work, as noted yesterday, economists until now have offered only a collective shrug and an admonishment to just accept this withered state as if we should be grateful it’s not worse.

“Get used to it,” said Ethan Harris, co-head of global economics research at Bank of America Merrill Lynch in New York. “We’re just a lower-growth economy now. Within the random noise of the data, in any given year, it’ll be normal to get a near-zero quarter every year. It won’t necessarily be the sign of something bad happening.”

How did we become a “lower growth economy now?” It is, to the mainstream, just some big mystery apparently not worth the effort to explore. Thus, they downplay the costs of this “get used to it” when in fact they are enormous and getting still larger with each passing “random noise” quarter.

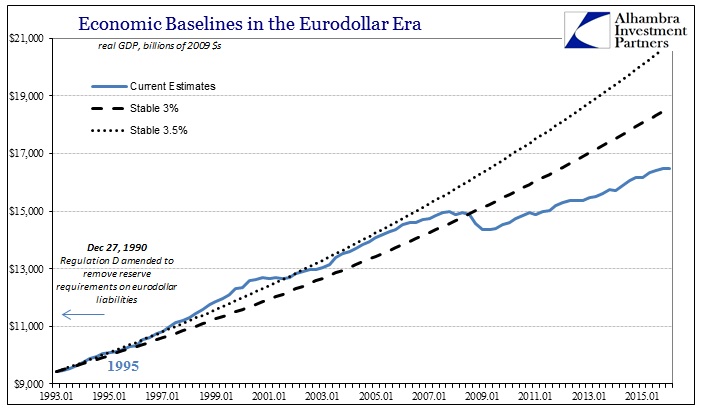

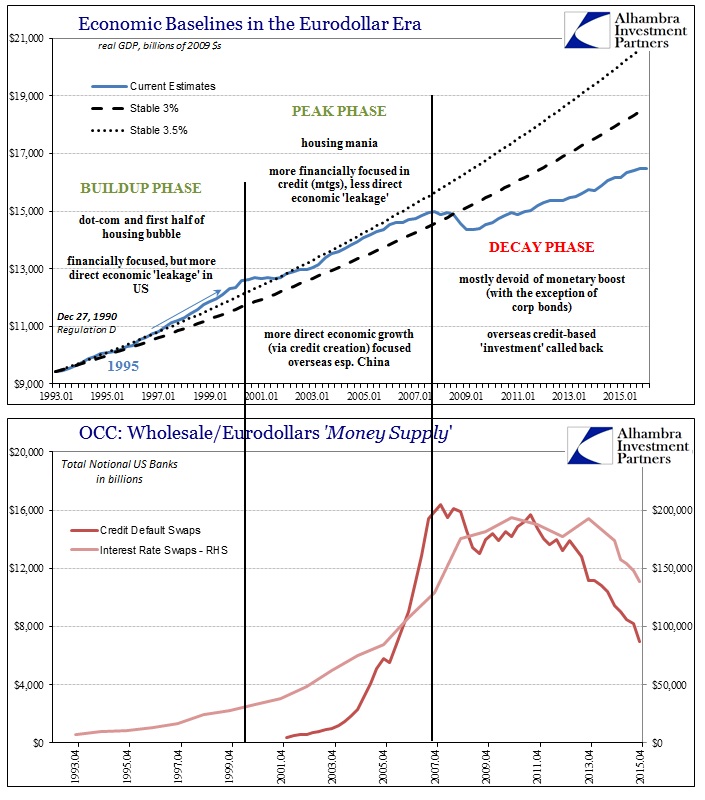

Dating back to the early 1990’s, there is every reason to believe that a 3% to 3.5% baseline in growth is appropriate. That is actually a downgrade from the 1980’s, but more consistent with prior historical periods. As is clear on the chart immediately above, despite continued insistence in the mainstream of recovery, even GDP conclusively demonstrates its absence. It also shows this highly suspicious deviation on its two fronts; that the economy fell off severely in the Great Recession, and then that the recovery thereafter just continued further below trend even though it had already shrunk so much at the contraction.

The net result in terms of immense opportunity cost is where the economic trajectory (as viewed by GDP as a proxy) got pushed quite far below the prior baseline but also that the positive numbers of this “recovery” are not nearly positive enough so that the gap only grows larger. And that has remained the case no matter what or how “stimulus” is offered. In fact, the incidence of “stimulus” is positively correlated with the increasing deviation even dating back to the Asian flu (Greenspan’s first “maestro” performance).

Since the housing bubble turned in 2006, GDP has traversed below the lower boundary (I define it here as 3%) baseline with the breach reaching now multi-trillions. It had fallen below the upper boundary in the dot-com bust, key clues as to the mechanism for these increasingly harsh economic conditions. That is perhaps the worst part of all this, as there really isn’t much to figure out – this is not difficult to grasp for anyone paying attention at all during this century. These slowing impulses perfectly align with the asset bubbles and their acute failure points; all that may be missing is a more complete explanation of their monetary basis and the general contrivances for economic transfer (or reduction of transfer) before and after them.

That is what the study of the eurodollar system offers; a (nearly) completed picture of our deepening plight.

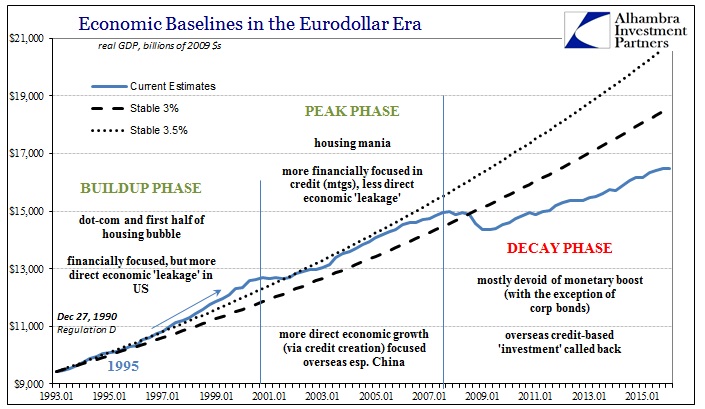

The first period of the “mature” eurodollar system boosted economic growth because the manner in which money creation (via credit) “leaked” into the real economy was more direct and robust (IPO’s of really worthless tech companies that did have an immediate, artificial effect on both hiring and capital investment; it was such a heavy trend that it fooled the Fed into thinking it was a natural surge in productivity, which they then took credit for).

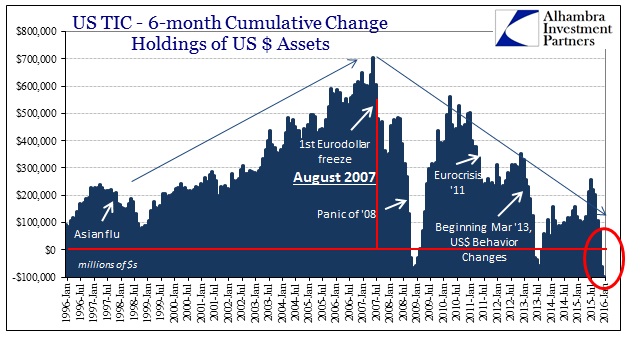

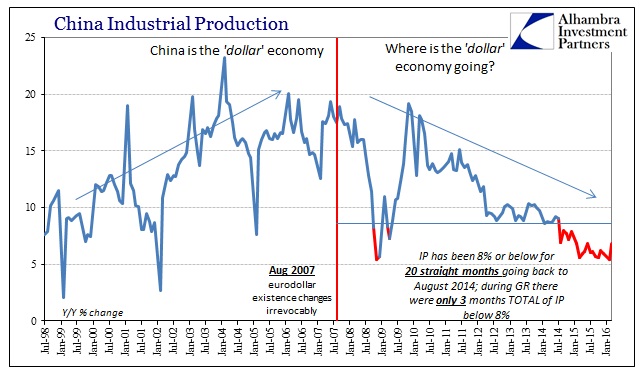

After the dot-com bust, however, the eurodollar shifted into its mania phase which was far more contained within the financial system itself. The only leakage domestically was primarily mortgages directed at consumption, the appearance of houses-as-ATM’s. It was a relatively weaker supplement to the weakening economic base, as the BLS shows in the sudden decline in labor output and utilization at that time (below). But where eurodollar expansion was “funding” marginal US consumption, it was in parallel “funding” overseas productive investment especially in China.

What we find in GDP inside these phased borders is consistent with evidence all over the eurodollar system. We can observe, for example, the changing character of the system itself into an even more highly financialized focus in the “peak” phase, compared to the buildup phase that preceded it, with the really unbelievable burst in credit default swaps over and above the rising base level of derivatives in interest rate swaps.

We find these same trends or phases all over the world. Economists confused them as “capital flows” and productive investment when instead they all relied on credit-based “money” that was having great distortive effects everywhere it infected. As I write today, US workers have every reason to be angry about the state of the economy and the quite distinct lack of opportunity it offers. The BLS calculates that total hours worked in Q4 2015 were only 2% more than the start of that second eurodollar phase in the middle of 2000. Despite that almost incomprehensible downshift in the real economic base, the number of potential labor (civilian non-institutional population) has swelled by 41 million, or +19%.

As bad as it is here (and makes a complete mockery of “get used to it”) it is actually worse in those countries that have received what used to be US jobs. In other words, there is a vast difference between “capital flows” that were assumed by economists and the credit-based reserve currency that expanded via bank balance sheets, making the entire global economy on both sides susceptible in this eurodollar decay phase.

Even those countries that have “taken” jobs from developed world manufacturing are struggling and to an even greater degree now than the nations that lost them. It’s not just American workers that have been robbed of opportunity, the stimulus-weary global economy is sharing that misery on all sides.

Again, it was never “free trade” nor capitalism. Populists on both sides deride and decry them, but in reality they are really against the monetary versions that have been put forth in their place. Thus, the populists are right about what it is they actually perceive but wrong as to why that is, while economists are actually right to defend free trade as a concept but utterly wrong and guilty about what they have instead delivered. It was always financialism propagated through the credit-based reserve currency of the eurodollar. As it declines, everybody loses.

That is what we find globally, almost perfectly synchronized so that it takes actual effort not to see it. The shroud of orthodox ideology, however, may finally be softening, though it is far from clear whether or not that could be a positive result. Paul Krugman in a shared appearance with Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe in late March actual deviated from the hard “truth” orthodox economics has long held about money and closed economic systems (thanks to L Bower for finding this):

I really want to make four points. The first is that we are now in the world of pervasive economic weakness. In many ways, we are all Japan now. This complicates policy for everyone including Japan. The second is that the linkages among major economies are strong. They are stronger than much conventional economic discussion suggests, largely I would argue because of capital flows. This is very important to speak about. The third, which may be of particular concern here is, we are seeing the difficulty in achieving goals through even very bold and unconventional monetary policy.

All those points are related by the same thing! They are at least starting to “see” the problem even if they still yet refuse to completely break out of their useless dogma. Weak global growth is due entirely to mistaken monetary assumptions, which explains why “stimulus” never worked anywhere it was interjected. It is not, however, nor has it ever been, “capital flows.” The true impetus of “capital flows”, that which binds all of this together, was never “capital” but the credit-based “money” of the matured eurodollar system.

Perhaps this is a good first step as actually, and out loud, admitting that the “closed system” view was always a mistake is a profound shift for someone as orthodox as Krugman. As he later said, “The interdependence of the major economies is, I will argue, very large. Ordinarily, the view that I and others have is that the interdependency is limited because even now international trade flows are not that big.” They assumed mercantilism as the global basis when instead, especially in the 1990’s forward, it was financialism. That is an enormous distinction that explains why the global economy is where it is and also why economists can’t figure that out (many have just given up trying, preferring to hold on to their position by blaming the economy instead).

So we are stuck choosing only between those economists that want you to “get used to it” and those that see the very big costs of doing so but remain frustratingly, maybe criminally, wed to their past beliefs even though the past quarter (half) century of monetary history shows they were wrong the whole time. The problem, as should be obvious, is that the longer they take to first become curious as to why the US and global economy might be and remain in such relatedly dire shape and then become open minded enough to figure it out, the bigger the costs will be likely far beyond the enormity of it now. Economic opportunity especially in lost time of compounding cannot truly be appreciated even in the raw estimates of GDP baselines presented here. In the past, such sustained deviation leads not just to further economic misery, which we already find far too widespread, but broad and unfortunately destructive social upheaval.

In short, there is every reason in the world to actually figure out what is going wrong and to eventually try to fix it. This “get used to it” idea is right now the most dangerous sentiment anywhere on the face of the earth. The hardened and inflexible line of orthodox economics is not far behind.

Stay In Touch