As usual, everyone is focused on the wrong part of the FOMC statement. There is already a lot being made about the one sentence inserted as “hawkish” sentiment that puts the economy, supposedly, back on its fruitful, “full employment” track. In a clear sigh of relief undoubtedly in relation to the scary May payroll report, the July 2016 FOMC statement confidently announces:

Near-term risks to the economic outlook have diminished.

Why anyone would give it any weight at all is a mystery. The FOMC has been making the same declaration intermittently for almost two years; only to have to retract it as “global turmoil” randomly, in their view, intrudes.

What truly disqualifies the economic assessment, indeed all their economic assessments, is not what changes from meeting to meeting but what remains. One year ago, just as the summer was about to heat up in far too many ways, the July 2015 policy statement included this passage:

Inflation continued to run below the Committee’s longer-run objective, partly reflecting earlier declines in energy prices and decreasing prices of non-energy imports. Market-based measures of inflation compensation remain low; survey based measures of longer-term inflation expectations have remained stable.

The version in July 2016 says this:

Inflation has continued to run below the Committee’s 2 percent longer-run objective, partly reflecting earlier declines in energy prices and in prices of non-energy imports. Market-based measures of inflation compensation remain low; most survey-based measures of longer-term inflation expectations are little changed, on balance, in recent months.

These exercises in futility are ridiculous, particularly parsing these rudimentary statements of faith rather than science, but given that so many people especially in the mainstream media pay attention it remains a tedious necessity. The only meaningful difference between those two passages is just one word, “has.” The inclusion of the word actually makes a mockery of what follows it, as it calls into question “earlier declines in energy prices” and those of “non-energy imports.” These are references to the “dollar”, but worded such that we are led to believe there is nothing concerning here.

We know that because the FOMC statement in both July 2015 and July 2016 repeats its “inflation” promise in one other place. July 2015:

Inflation is anticipated to remain near its recent low level in the near term, but the Committee expects inflation to rise gradually toward 2 percent over the medium term as the labor market improves further and the transitory effects of earlier declines in energy and import prices dissipate.

July 2016:

Inflation is expected to remain low in the near term, in part because of earlier declines in energy prices, but to rise to 2 percent over the medium term as the transitory effects of past declines in energy and import prices dissipate and the labor market strengthens further.

The latest statement now references “earlier declines” which we easily assume means the same decline (crash) in oil prices and global activity that happened near the end of 2014 and the outset of 2015. In other words, despite it being a year and more than a half later, what happened under the “rising dollar” is somehow still expected to be “transitory.” The reason it is thus to the FOMC? “Near-term risks to the economic outlook” always diminish in the middle of every year.

In reality, the Federal Reserve economists have no idea what is happening and why inflation hasn’t responded to QE. This is not a trivial discrepancy, as monetary policy and balance sheet expansion should have very direct and obvious effects (“money printing” and threats of it are the core elements of monetary theory and policy). The economy in late 2014 to them signaled nothing but clear sailing, but instead it suddenly and globally fell off; yet they still are looking for that clear sailing as if the entire global economy contracting in synchronized fashion is just some random fluctuation of no particular concern because they view money from perspective of QE.

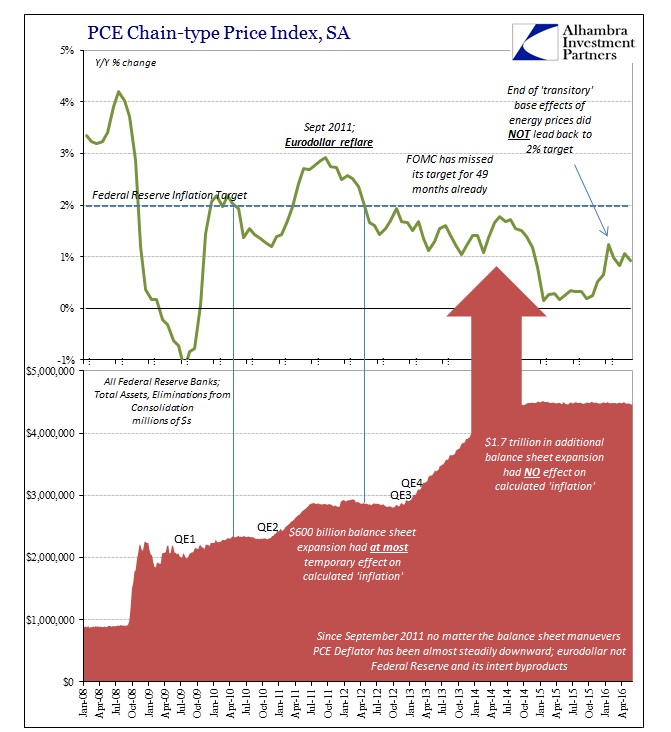

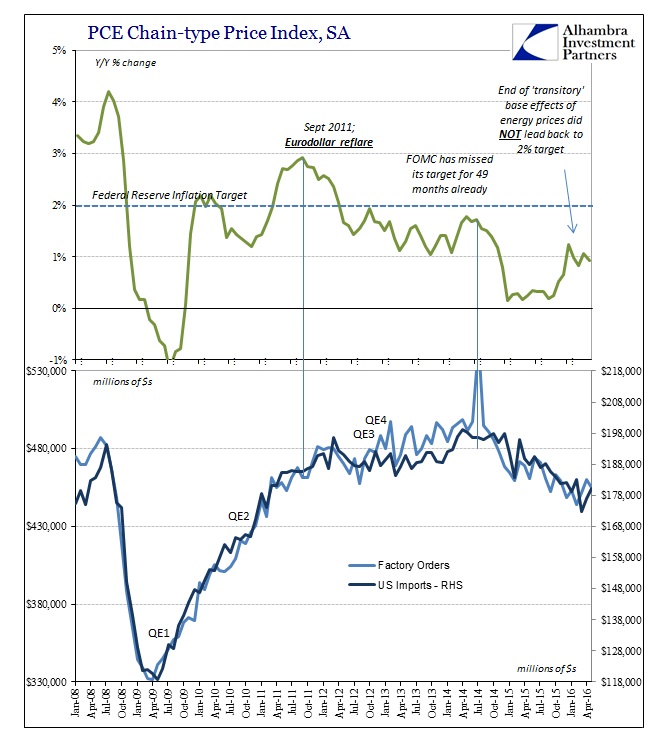

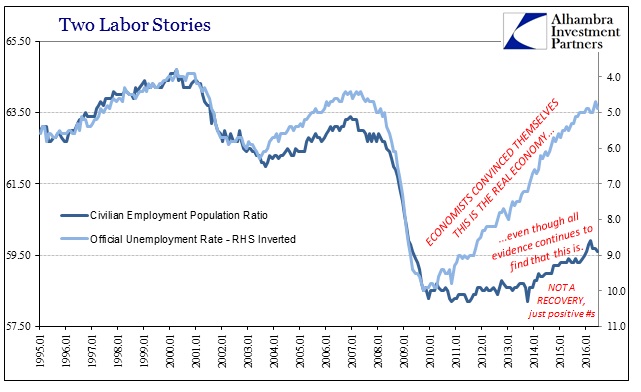

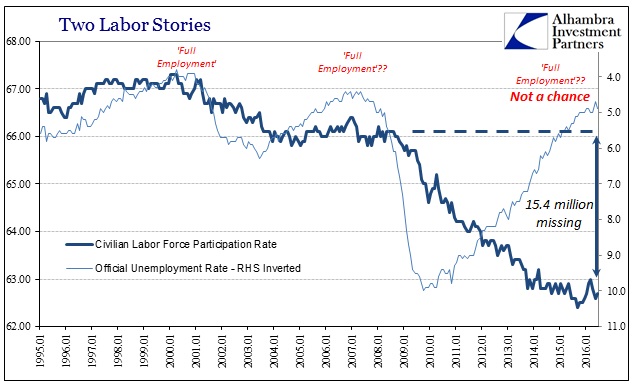

But the real problem is the longer-term aspect of still having to make these inflation claims in each and every FOMC statement going back a long, long way. It has been 49 months since the PCE deflator was at or above 2%, with $1.7 trillion in additional balance sheet expansion since then. What that proves is that the FOMC’s entire theory of inflation is totally wrong; orthodox theory expects that the sharp drop in the unemployment rate will bring about “transitory” when in fact there is every reason, by virtue of the PCE deflator’s persistent and increasing miss, to suspect the unemployment rate of being misleading (perhaps highly so).

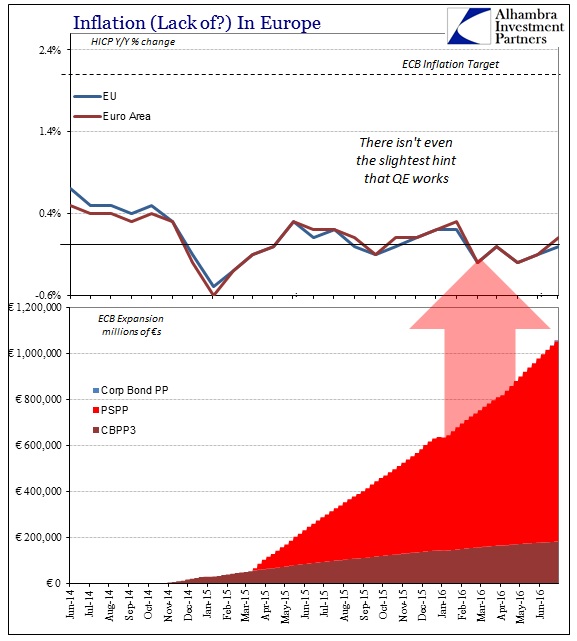

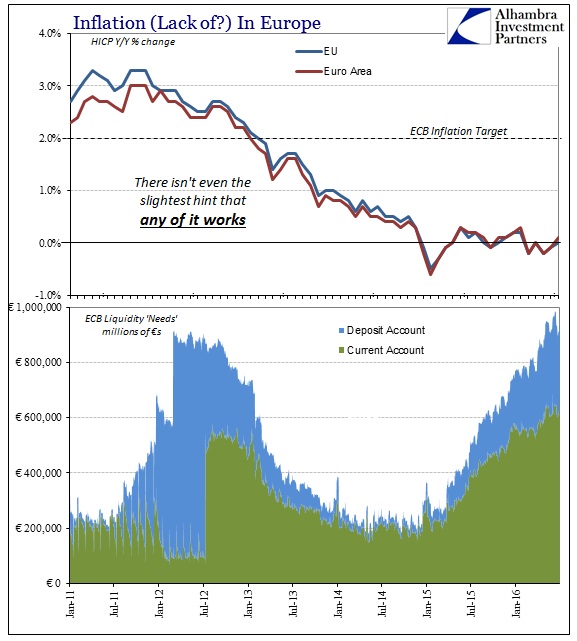

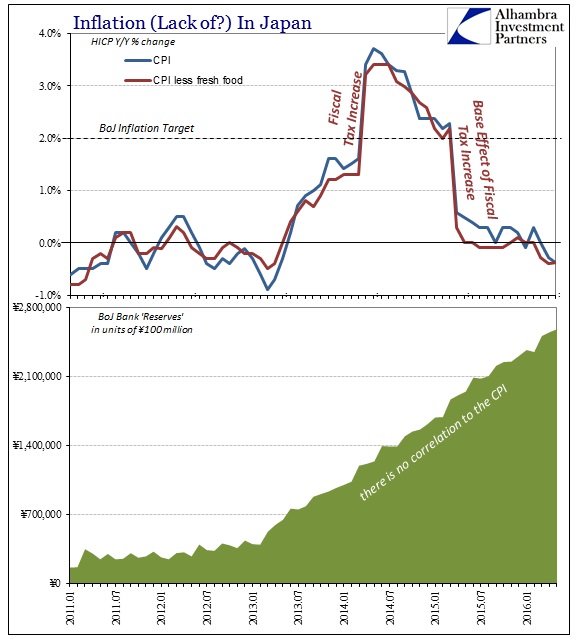

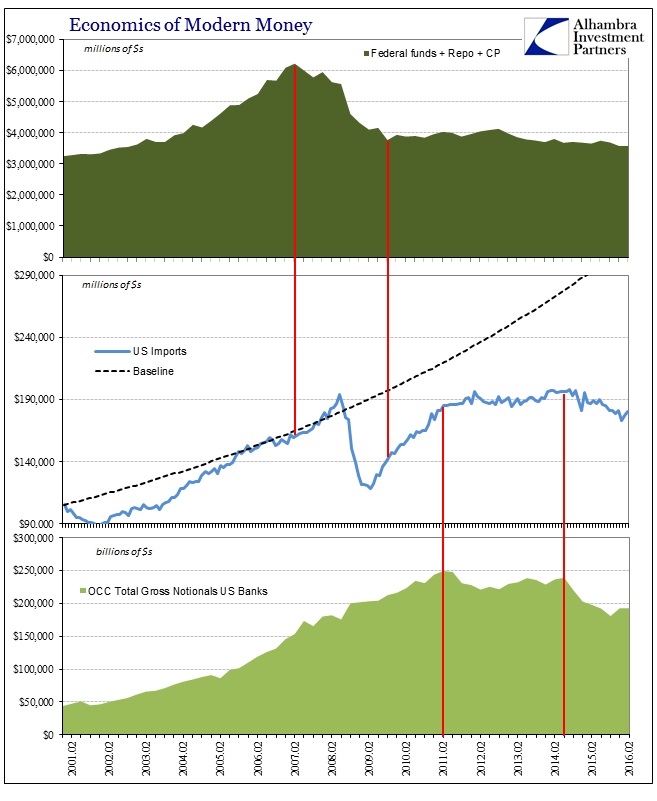

This is not an indictment unique to the US; it has happened all over the world wherever QE or any other method of liquidity or balance sheet expansion has taken place. Because of that uniform empirical refutation, the problem is not specifically the Federal Reserve in its execution of QE within the unique circumstances of the American banking system. Rather, it can only mean the theory itself is flawed, starting with the foundational premise that bank reserves play anything other than an incidental role in actual money and banking relevant to the real economy.

While ideological commitment to orthodox monetary views leads only to mystery, it isn’t at all difficult to find a correlation that begins to suggest what is really going on – and it has nothing to do with monetary policy except by obvious omission.

I really don’t know how much clearer it could possibly be. Inflation follows almost exactly the trend in US “demand” flowing to manufacturing, both here and overseas; in other words, US consumers. Further, as demonstrated yesterday, there is an equally obvious monetary component(s) that explains these changes in “demand.”

All of the necessary elements are here: money to demand to inflation. Because of this reduction in money then “demand” then consumer prices, the whole point of “full employment” as it is being used in the mainstream is off by a significant factor; an observation also easily made through the whole perspective of the labor market (including inquiry about the denominator in the unemployment rate, not just the numerator).

In short, the FOMC keeps expecting inflation, and thus the whole economy, to resolve to its bank reserve policy when in fact the entire global economy, with the US and US consumers with it, are directly impacted instead by eurodollar behavior in the form of ongoing, persistent (therefore not “transitory”) money destruction. It is a textbook case that would immediately conform to the most orthodox view except for the one variable – money.

The Fed has no idea what money is in the wholesale, eurodollar sense, and therefore its policy statements are only relevant in what they have to keep repeating, not at all what they say about diminishing economic risks. The FOMC has no idea what those risks are, as if any layperson couldn’t tell just by their confusion and highly variable confidence the past two years that were never supposed to be so arguable in the first place. Transitory means temporary, not “we don’t have any idea.”

Stay In Touch