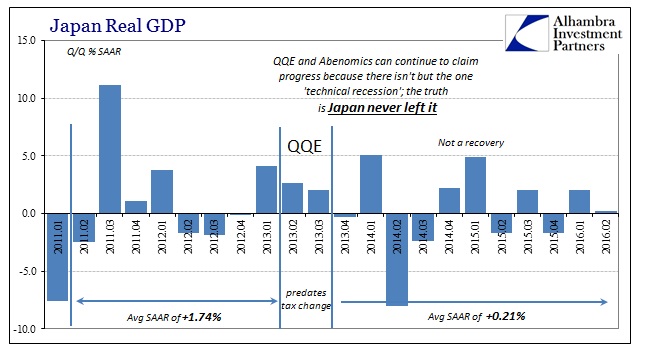

In June 2015, Japan’s Cabinet Office, the section of the government charged with tabulating and publishing gross domestic product estimates, revised Q1 2015 GDP significantly higher to 3.9% from its preliminary 2.7% figure. Not only was that the second straight quarter of positive growth, the acceleration indicated seemed to confirm that the Japanese economy had finally shaken off the effects of the tax hike in 2014 while also responding favorably to QQE’s expansion at the end of October 2014.

“This is a pretty positive figure and shows the recovery is picking up pace,” said Takeshi Minami, chief economist at Norinchukin Research Institute.

“Non-manufacturers are boosting spending on expectations that private consumption will recover, so this should serve as a key driver of growth,” he said.

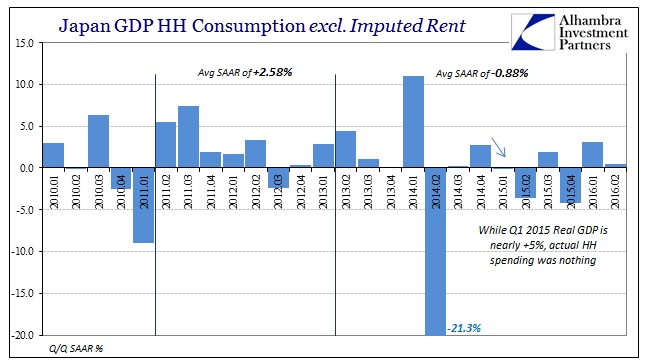

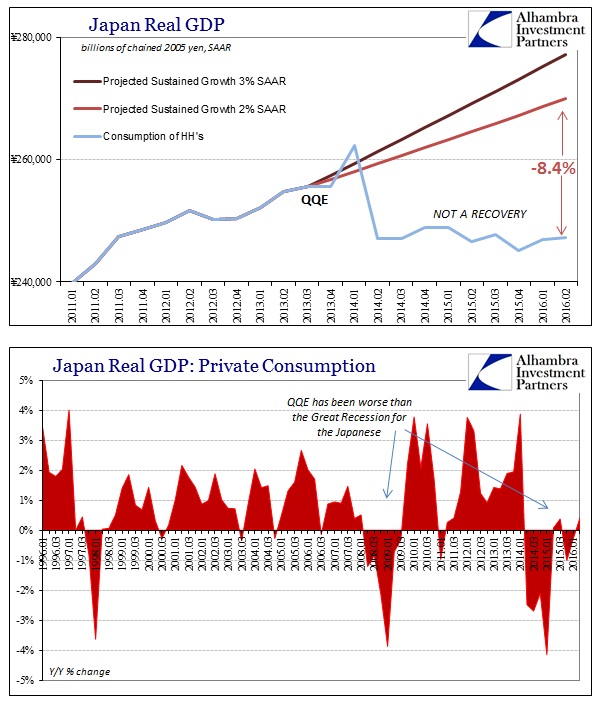

Other economists were more cautious, and rightly so. There was no evidence even at that time that Japanese households were about to relinquish their unrelenting grasp of their tight wallets and purse strings. Household consumption less imputed (meaning made up) rent was actually slightly negative in Q1 despite what is now believed to be nearly 5% GDP growth. Thus, like Q4 2014 GDP in the US, many economists were only seeing in Japan what they expected.

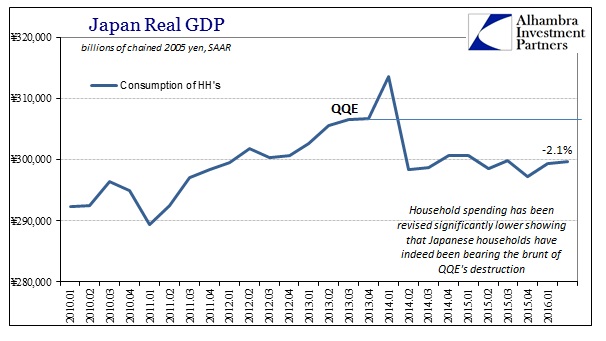

Consumer spending in Japan has remained subdued throughout QQE – even in this supposed post-tax period. There has never been any evidence that consumption did respond to QQE “stimulus” let alone a second round of it. That was expected even by those counting on QQE to work, at least in the beginning. Policymakers knew full well that Japanese households were going to bear the burden of what they believed only a temporary adjustment. After being hit by the weakened yen in the form of consumer prices, which the tax hike amplified, the Japanese people would be rewarded their sacrifice in the bountiful and sustained recovery that followed.

Though the shocking weakness after the tax change was deeper and lingered longer than expected, GDP at least on the topline finally suggested to economists that the end of the adjustment period was finally at hand. It was confirmation bias unwarranted from the actual state of Japanese households; they were not bearing the burden of adjustment, they were plain decimated by it, a condition that consumers have yet to recover from.

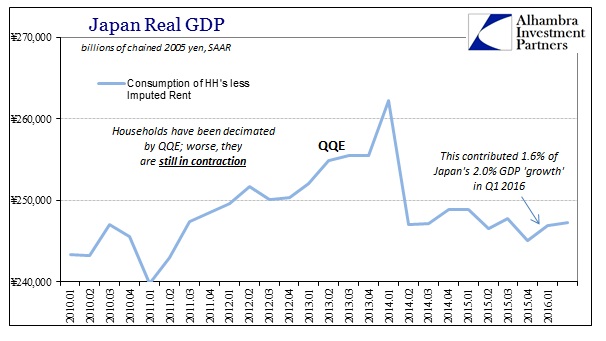

Even last quarter when GDP was once again significantly positive, now revised to +2.0%, economists and policymakers made more out of consumption figures than was indicated by the full context of them. Since GDP measures quarter-over-quarter changes, it is susceptible to just this kind of improper extrapolation. In this case, it is the uneven nature by which Japanese households have been forced to cut back spending.

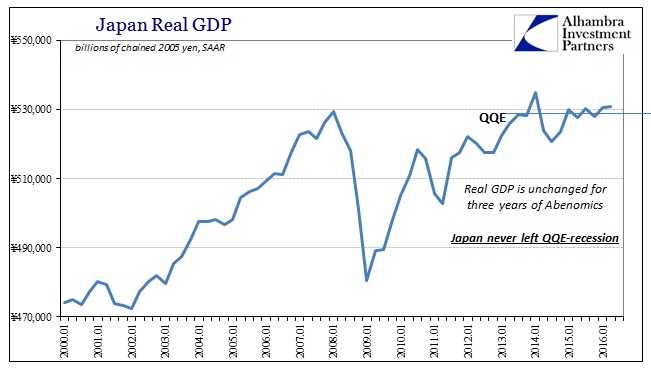

Thus, rather than Q1 2015 GDP indicating the start of the full recovery, it was merely one more false positive; Q1 2016 being the latest. In the five quarters since, real GDP has been down, up, down, up, and now down again (just 0.2% in Q2 2016).

Every time GDP is up, it is talked about in the media as the start of something; when down, it is but a temporary setback. The problem is that nobody accounts for the lack of progress since QQE began. This uneven trend is even worse than obvious recession because it gives policymakers enough mainstream ambiguity by which they can continue to deny the huge hole they put the Japanese economy into. Since there hasn’t been two straight quarters of GDP contraction, the “technical” definition of recession that actually isn’t used technically anywhere but the media, Japanese officials can still talk about this as if it were at least small measures of progress.

“Japan’s economy is likely to achieve a recovery driven by private demand though the government must be mindful of risks such as slowing emerging market growth and uncertainty over the fate of Britain’s exit from the European Union,” Reuters quoted the country’s economy minister Nobuteru Ishihara as saying.

Some temporary factors, such as the fall in tourism following two deadly earthquakes in April, were behind the weakness in private consumption, Ishihara added.

Japan’s economic problems in Q2 have nothing at all to do with Brexit, tourism, or “slowing emerging market growth” (though that one is at least related). For all the bluster about monetary policy and the excuses it allows by avoiding recession, its positive effects should be obvious by now more than three years into it. Yet, even in GDP, which is again constructed to be the most charitable measure of economic growth, it is the lack of growth and progress that is most obvious and evident; starting with unevenness.

Setting aside the huge decline related to the earthquake and tsunami in Q1 2011, there was clearly more economic momentum before QQE than after it. Lack of growth, even in Japan, is recession. Continued lack of growth, even in Japan, year after year after year (entering a fourth year) is depression. And the reason for it is the massive burden that was placed on the Japanese people under the flimsiest of pretenses – that a recovery and then sustained growth can be achieved by first hugely negative factors. Japan is the only place in the world, “thanks” to the yen, formerly, where the policy actually accomplished that first part.

Policymakers definitely delivered on the negativity, but are now stumped as to why that hasn’t been spun forward into everything they promised more than three years ago. That is why they are left to (over) emphasize every small positive in order to deflect from having to explain it all. The lack of declared recession or even the appearance of a “technical” one is fit into the binary model of orthodox economics; if it isn’t recession then it must be getting better.

Nowhere in the world is the fallacy of that statement more easily demonstrated than Japan and its households. Like everywhere else in the world, economists still have two facets to explain – the contraction and then the lack of recovery that followed it. Given the first, the second is actually much worse than recession, the global calling card of monetary imbalance.

Stay In Touch