In February 2013, Federal Reserve Board Governor Jeremy Stein gave a speech at a research symposium produced by the St. Louis branch of the Federal Reserve that shocked quite a lot of people. QE3 and QE4 were still quite new, but here was a Board member talking just months after their start of “reach for yield.” His assessment of risks in the respect of financial imbalances was not limited to that one avenue, but, as you can appreciate, that is all anyone remembers of it.

The third factor that can lead to overheating is a change in the economic environment that alters the risk-taking incentives of agents making credit decisions. For example, a prolonged period of low interest rates, of the sort we are experiencing today, can create incentives for agents to take on greater duration or credit risks, or to employ additional financial leverage, in an effort to “reach for yield.”

The concerns over “a prolonged period of low interest rates” has been intermittently expressed and not just in relation to junk bonds and credit markets in the three plus years since then. The FOMC has debated (against itself) by trying to get a sense of how risks are balanced, economic to financial. If the economy is weak, then financial risks are, in their view, worth taking – even if “markets” take that to extremes.

In the minutes for the December 2013 FOMC meeting, for example, the economy was believed to be well on its way toward completing the recovery trajectory. They had decided at that meeting, after forcing unnecessary (for reasons contrary to their expectations) uncertainty that summer, to taper the last two QE’s because the economy’s recovery trajectory gave them opportunity, so they believed, to address more the financial risks – not just “reach for yield.”

In their discussion of potential risks, several participants commented on the rise in forward price-to-earnings ratios for some smallcap stocks, the increased level of equity repurchases, or the rise in margin credit. One pointed to the increase in issuance of leveraged loans this year and the apparent decline in the average quality of such loans.

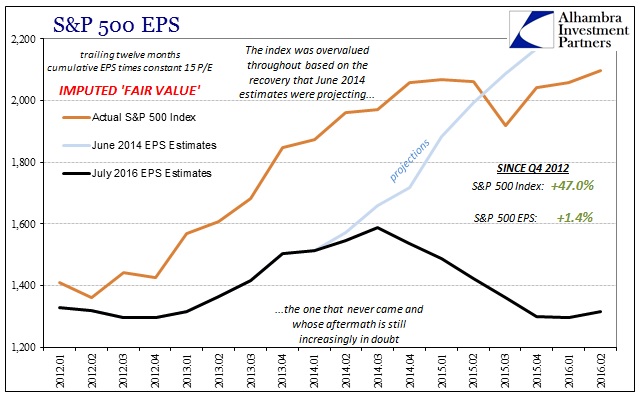

As it has turned out, forward price-to-earnings ratios have been far out of historical ranges for much more than smallcap stocks. Trailing-twelve-month earnings for the S&P 500 were $86.51 in Q4 2012. Since Jeremy Stein first introduced the official warning about financial risks, ttm earnings have increased a total of 1.4%, currently figured to be just $87.73 in Q2 2016. Over the same three and a half years, however, the index has gained nearly 50%.

The reason for this misalignment in FOMC terms is the false assumption that risks between finance and economy can or must be balanced. What we find over the past three years is risks to both that were much deeper and intractable than orthodox economists seem capable of understanding. They didn’t mention large cap stocks at the December 2013 FOMC meeting because it was fully expected that the economy would take care of any valuation stretching; indeed, expectations among stock analysts were for rapidly growing earnings forever onward that would validate the recovery as well as surging share prices.

EPS did rise to more than $100 by the middle of 2014, but by then the market was priced as if $140 to $150 were likely – the same as what the FOMC saw for “balanced” risks. Thus, it is this “rising dollar” period that economists and stock investors seem unable to grasp.

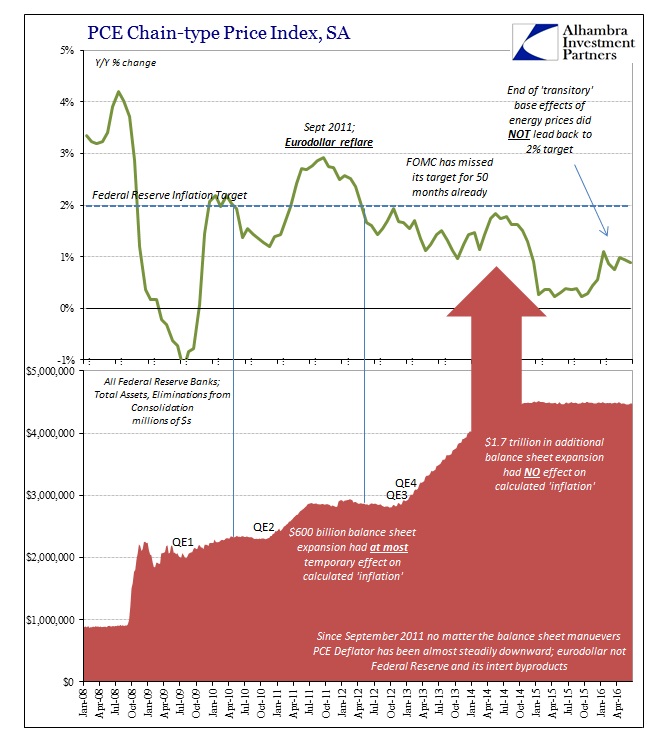

Nowhere is that more evident than the perpetual ritual of paying faithful homage to “temporary” or “transitory” inflation; meaning the fact that so much “money printing” doesn’t seem to have any effect on maintaining what is supposed to be a more rigid monetary policy target of 2% for the PCE Deflator. One year ago, in the minutes of the July 2015 FOMC meeting, released on August 19, 2015 (a little more than a week after the yuan “devaluation” that thoroughly confused policymakers and most anyone else, and less than a week before the related mini-crash in global stocks) Committee members were dutifully reciting what clearly wasn’t nor isn’t true.

Although most readings on longer-term inflation expectations were little changed recently, participants discussed how to interpret downward movements in some survey and marketbased measures of inflation expectations over the past few years. Most participants still expected that the downward pressure on inflation from the previous declines in energy prices and the effects of past dollar appreciation would prove to be temporary.

And so they judged the risks “as nearly balanced” yet again, as if it were still December 2013; which was taken to mean a September rate hike even though events at that time (the release of the minutes, though there were enough irregularities that the late July discussion should have factored them had the Fed not continued past 2008 with its antiquated understanding and framework) indicated growing concern. It will be about five years before the full transcripts are released and we can finally know for sure whether anyone had the guts to ask either the staff or the other members to explain the most basic monetary incongruence of inflation – low consumer (calculated), high asset.

Not sensing what was plain right in front of them, the July 2015 minutes further stated:

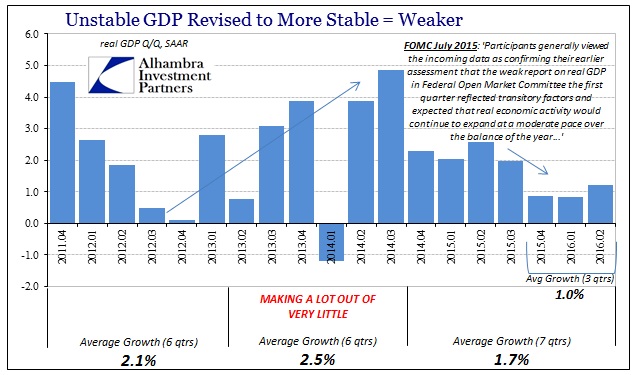

Participants generally viewed the incoming data as confirming their earlier assessment that the weak report on real GDP in Federal Open Market Committee the first quarter reflected transitory factors and expected that real economic activity would continue to expand at a moderate pace over the balance of the year, leading to further improvement in labor market conditions.

The BEA in the quarters since has taken care of the contraction in Q1 2015 GDP, but that didn’t do much to solve the balance of risks. Stock prices are marginally higher even though earnings continue to be stuck at 2012 levels as each quarter passes by. And yet, the FOMC continues to repeat its inflation stance (using “transitory” this year rather than “temporary” as last year).

Inflation was expected to remain low in the near term, in part because of earlier declines in energy prices, but to rise to 2 percent over the medium term as the transitory effects of past declines in energy and import prices dissipated and the labor market strengthened further.

They include this statement even though the staff’s updated model projections now show inflation remaining below 2% into 2018! Inflation is, for lack of nuance, the final measure of monetary policy and overall economic effectiveness and efficiency. When it rises, the Fed has done its job particularly in the context of continued “stimulus” or “accommodation.” But when it doesn’t as it hasn’t for more than four years now, the entirety of QE3 and QE4, the FOMC will not allow itself to even consider the opposite conclusion. Instead, its failure to account is “transitory” or “temporary” even if every single FOMC statement must repeat and emphasize those words meeting after meeting until they lose all meaning.

To acknowledge that inflation isn’t temporarily dissuaded by irrelevant or transitory factors would be to further admit that economic and financial risks can never be so balanced. It is the monetary policy trap that is way beyond what Jeremy Stein warned about more than three years ago. Economic risks are still very, very high, a fact stock investors should pay more attention to in just earnings alone, which only further presses financial risks due to the fact that “investors” were counting and betting on QE to actually work and deliver economic growth eventually proved by consumer inflation. Again, risks do not balance, they are self-reinforcing.

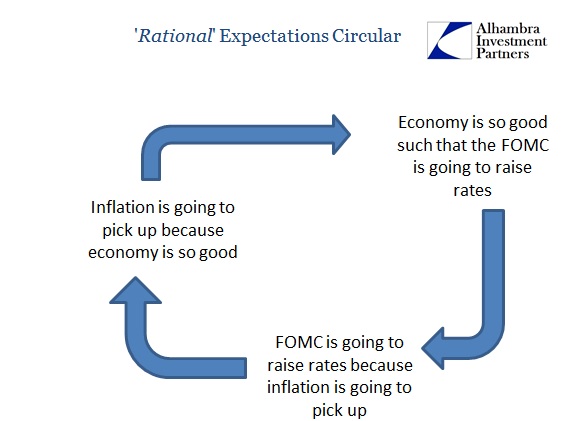

But because the FOMC is deliberately avoiding its own core inflation deficiency, they are once again talking like 2013.

Some Fed officials also worried that a prolonged period of very low rates could cause investors to misallocate investments or misprice risk, possibly leading to a destabilizing financial bubble and bust.

The chart on earnings and valuations for the S&P 500 at the beginning of this post identifies clearly what risk has been mispriced – belief in monetary policy. QE was supposed to deliver a full recovery in the real economy that brought with it sustained earnings growth that would eventually justify the immediate, exuberant mainstream embrace of QE3 and QE4. Thus, the lack of inflation is and has been a major warning that to continue to expect that validation is a very dangerous proposition. No inflation, no recovery, no earnings. That pretty much describes 2015 and 2016 so far.

The issue is entirely the dollar, or more precisely the “dollar.” The FOMC doesn’t know what to make of it, especially these past few years where nothing has gone as it was supposed to. At first, they tried to claim that the “rising dollar” of funding distress and currency chaos was the “strong dollar” of old, as if that condition could ever mean anything other than rock solid stability. Now it’s all just “global turmoil” or “overseas risks” because the unemployment rate in the US is all that is allowed into the FOMC bubble.

Yet, they have to keep prevaricating on inflation. It’s the only way they can claim that risks are balanced, and it prevents them from seeing the circular logic that funding markets are once again betting heavily against. The only risk that matters is widespread realization economists and policymakers have no idea what they are doing. Credit and “dollar” markets long ago made that determination and have been proven right. All you really need are the FOMC’s inflation statements to confirm that assessment.

Stay In Touch