In December 2000, the Financial Post orchestrated what it billed as a great debate, a clash of titans pitting two giants of economics against each other in a series of eight questions. Dubbed the Nobel Money Duel, on the one side was Robert Mundell, a Nobel Laureate often credited as the “father of the euro.” On the other was Milton Friedman, similarly a Laureate and often cited as the first monetarist and champion of the floating currencies that dominate our circumstances.

Even though it was at the time only a few years old, Mundell predictably lauded the euro as an exemplar of “how successful a well-planned fixed exchange rate zone can be.” Friedman was far more skeptical.

Will the euro contribute to political unity? Only, I believe, if it is economically successful; otherwise, it is more likely to engender political strife than political unity. And here, I believe, is where Bob and I differ most. Ireland requires at the moment a very different monetary policy than, say, Spain or Portugal. A flexible exchange rate would enable each of them to have the appropriate monetary policy. With a unified currency, they cannot. The alternative adjustment mechanisms are changes in internal prices and wages, movement of people and of capital. These are severely limited by differences in culture and by extensive government regulations, differing from country to country.

Though some Europhile holdouts will not yet submit, the past eight years have shown Friedman’s prediction prescient. There is a grave difference in how these kinds of basic national affairs are conducted, right down to the rudimentary terms of their construction and the rules by which they will operate. Though Friedman is often used to justify the floating world of today, what he championed in floating currencies is not what we find now.

Even arguing the terms of the debate with Mundell, Friedman stressed that there should be a trichotomy rather dichotomy in just examining the various options. Usually it is presented as a choice between fixed and floating when in fact what we often think of as fixed isn’t truly fixed. The third choice is actually the peg, a framework quite distinct from what he called fixed.

In his version of a floating currency, the central bank sets internal monetary policy but has no currency policy whatsoever. You can only pick one in order to allow righteous market forces to at least indicate imbalances. The fixed option, what Friedman called the “unified currency”, reverses the policy target; a currency board sets policy for the currency but can have no internal monetary policy. Another option under this view is “dollarization” whereby the country uses a foreign currency to set its own internal circumstances. In the classical setting of hard money or even physical currency, the domestic money supply is determined by its correspondence with foreign reserve changes.

As noted here, the Chinese system historically has come close to approximating this structure. The important difference, the one shared with how all floating currency arrangements evolved, is that it is not strictly a one-or-the-other arrangement. Most governments, as banks, try as best they might to have it both ways. As is clear in China, though the base of their arrangement was as Friedman proposed of the fixed system, it is absolutely the case that while the currency was fixed (and in many ways still is) the PBOC also had its own monetary policy.

To Friedman and to plain common sense, that is just an invitation to imbalance as well as the intrusion of politics. Similar to his main argument against the euro (that it was a child of political ambitions not economic), imbalance especially born of politics is an opening for disaster. In his famous, scholarly 1953 collection of articles, Essays in Positive Economics, one that he authored argued for floating currencies while also suggesting perhaps its weakness.

The argument for a flexible exchange rate is, strange to say, very nearly identical with the argument for daylight savings time. Isn’t it absurd to change the clock in summer when exactly the same result could be achieved by having each individual change his habits? All that is required is that everyone decide to come to his office an hour earlier, have lunch an hour earlier, etc. But obviously it is much simpler to change the clock that guides all than to have each individual separately change his pattern of reaction to the clock, even though all want to do so. The situation is exactly the same in the exchange market. It is far simpler to allow one price to change, namely, the price of foreign exchange, than to rely upon changes in the multitude of prices that together constitute the internal price structure.

Because it is much simpler to just change the standard clock time, there is always the temptation to use that simplicity for all the wrong reasons (an argument that Friedman never made until it was far too late). What has been developed of China and elsewhere is a hybrid system of fixed and floating. The “dollar” condition of the past few years, especially this “rising dollar”, has led to an ad hoc arrangement where various policies have become interchangeable at will. This was absolutely contrary to his stated purpose for all the works included in Essays; namely that Positive Economics demanded actual discipline rather than conduct by whim.

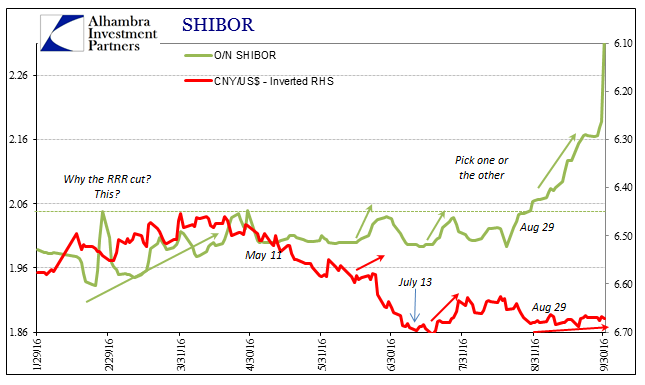

It is the literal truth in Chinese monetary and currency policy under the “rising dollar.” The PBOC has by turn targeted the currency and left the internal liquidity situation to its own market devices; or targeted internal liquidity and left its currency to its own market devices. Neither has worked out because both methods have been an affront to Positive Economics. In other words, market forces aren’t allowed to dictate imbalances for much more than a few steps or only so far before the market is shut down all over again. It is simply the veneer of markets but really the same old authoritarian approach that is in the background of all central bank policies and at an increasing rate today.

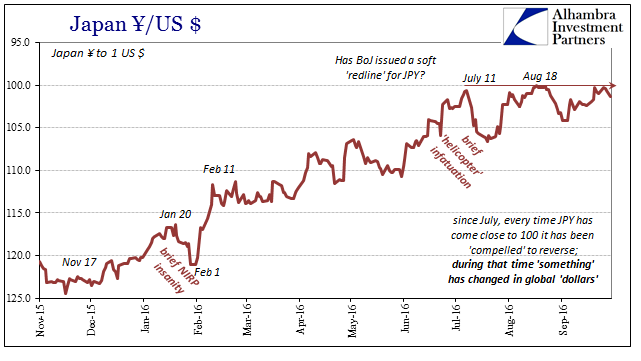

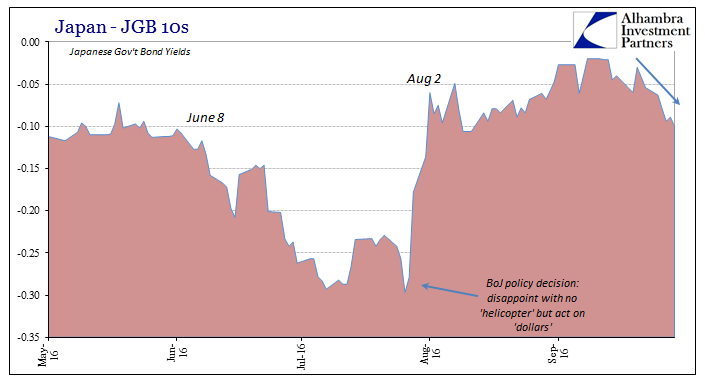

Though the mechanism isn’t yet clear, there can only be speculation as to the spread of hybridization especially to Japan and yen. The Japanese currency is treated as sacred – so long as it “obeys” monetary policy. Going back to last summer, however, JPY and the recoiling reaction of the market (“dollars”) flipped the whole thing. If BoJ wanted its monetary policy of QQE’s and whatnot (and there is more whatnot than is commonly appreciated) by Friedman’s common sense framework it should have tolerated market forces moving against it in at least the currency (demonstrating, effectively, that it didn’t work and thus delivering a verdict that perhaps BoJ should try something that might). Instead, the BoJ has tried time and again to have it both ways; internal monetary policies (disaster) as it sees fit while also maintaining only yen that is “friendly” to them.

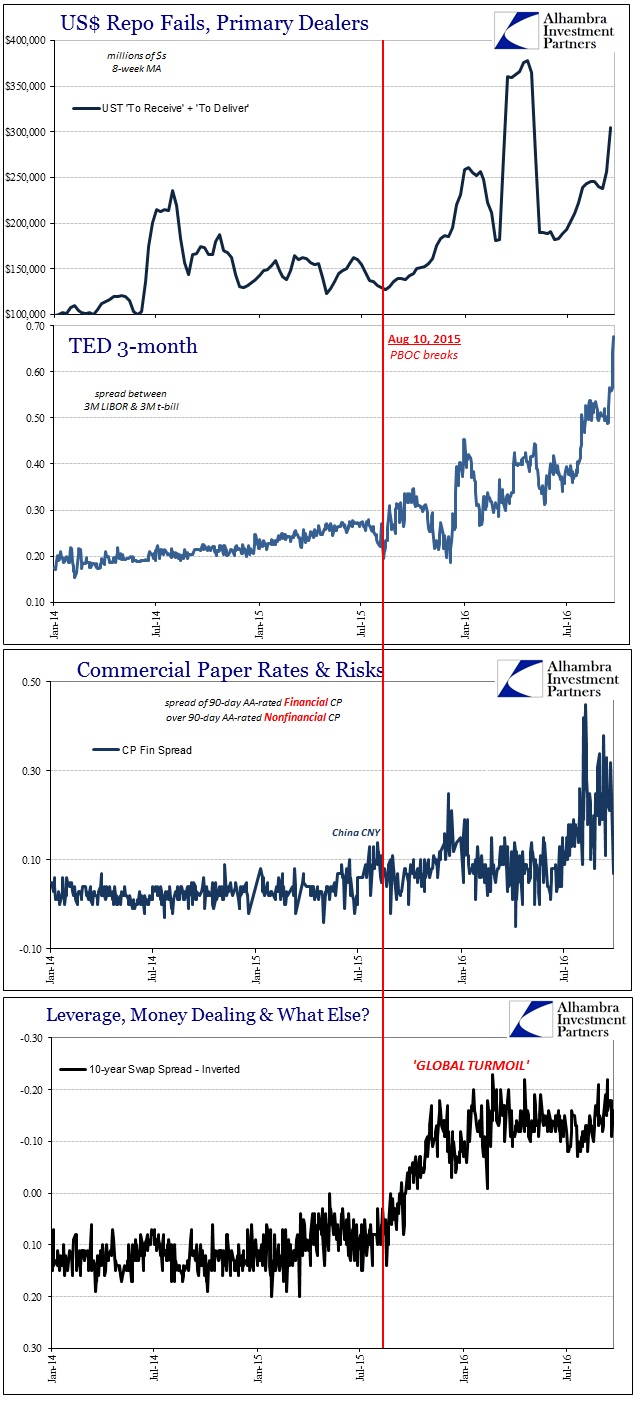

Disabling currency rejection has the effect of increasing pressure everywhere because there is no outlet. That was Friedman’s ultimate point, in that disciplined central bankers afforded the flexibility to have a greater say over a nation’s monetary conditions would still have to obey sometime rejection and be called on mistakes. Instead, as we see of both China and Japan related to “dollars”, nobody tolerates the mistakes for very long and so they only build up. But they are still subjected to the primal tradeoff – pick one or the other. As of the last few months, both the Chinese and Japanese have chosen currency, so it shouldn’t be surprising that markets are attempting to break out via growing illiquidity; “dollars” as well as RMB and JPY.

If I have to venture a guess as to one reason that there is “something” so different about global “dollar” liquidity especially in September 2016, it is that sudden attention to Asian currency. Maybe monetary authorities in both Japan and China realize that letting their currencies adjust on their own as they should leads to nowhere good, just as last year falling CNY was a surefire indication of further global financial problems and this year rising JPY doing the same. But establishing a hardline in currencies by whim, if that is the case for one or both, doesn’t solve anyone’s problems; it just moves them somewhere else with greater fury and intensity.

That is because Friedman was correct in his view of how this all should work; there is a role for the market, even where central banks and national policies don’t like the market’s judgments – like the “rising dollar.”

There is much to admire about Milton Friedman’s work and career, but in many ways it will always be haunted by this basic blind spot. The faceless market can be discliplined; central bankers might be at times, but they are human and respond as humans always have. The Socratic ideal of the enlightened Philosopher Kings of Kallipolis was always far too utopian to be realistic. Nowhere is that more true than when the introduction of political power destroys any tendency toward discipline that might have remained.

From the post-Great Depression view of that time, the market seemed far too messy and erratic, leaving many like Friedman to wonder if disciplined scientists given the proper power might be able to determine a more “optimum” outcome. This depression shows in almost every way there are no disciplined scientists at central banks; just power. The “rising dollar” and overall eurodollar decay is itself as much a rejection of the lack of discipline in every corner. Like the imposition of the euro, the eurodollar system has been driven more so by the politics of convenience (everyone loved it on the way up) than economics (small “e”). Now both are unpopular and nobody has any idea what to do about it because politics not economics still rules.

Stay In Touch