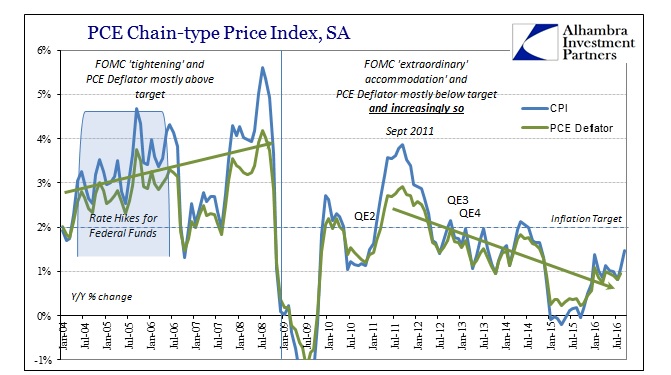

The headline CPI accelerated to 1.46% year-over-year in September, the highest calculated inflation rate for this index since October 2014. That was up from 1.06% in August and seemingly quite different than the -0.04% last September. To many, that looks like and is believed to be progress, an end to the drag of the dollar and oil. In many ways it was expected, as Federal Reserve officials have often noted the eventual base effects that would lift the rate.

That all, however, quite misses the point. Like the economy it is supposed to represent, the CPI rate should not fall off and then rebound in meandering fashion. First, there is the question of whether this is just normal variation rather than a rebound at all, given that the CPI is far more volatile than its PCE Deflator cohort. Unlike the latter inflation estimate, the CPI was last at the Fed’s 2% target in the middle of 2014, registering 2% or slightly more for four straight months until that July. Thus, the swings up or down are by themselves indicative of very little without corroboration. The CPI was 1.37% in January, very close to what it is now, and it meant very little then.

A sharp deceleration or even drop in prices, like economic output, should lead to an equal or sharper rise in prices (or output) after the weakness passes. The CPI was -2.1%, for example, for July 2009 and still negative as late as that October; but it finished the year at +2.7%, a nearly 5% swing from low to high in a matter of months. In the dot-com recession, the CPI bottomed out shortly after its end at 1.1% for June 2002. Just eight months later, it was back at 3% all over again.

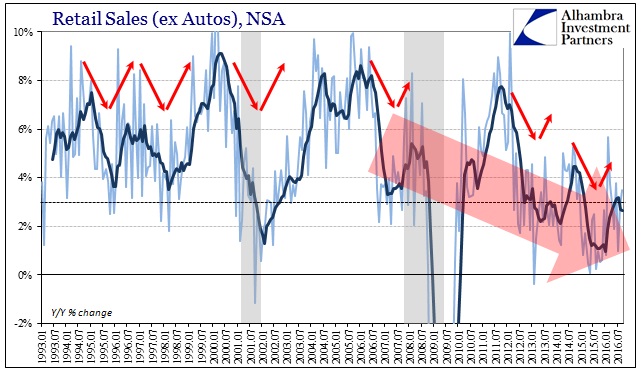

Yet, throughout this “recovery” but especially since the 2012 slowdown that is not what happens. Time and again the (global) economy absorbs a (monetary) shock which eventually passes but from which it doesn’t actually recover. This phenomenon is clearly observed in many accounts including, relatedly, retail sales.

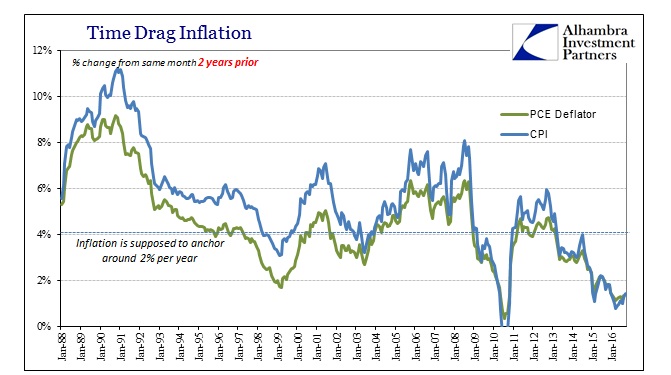

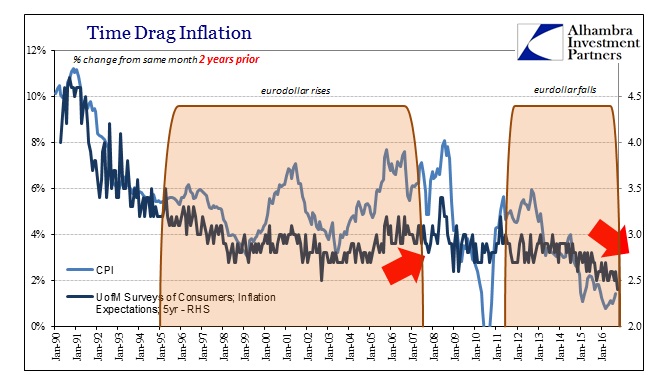

The net result is that the economy ratchets lower over time, where time is the key component/cost. In terms of the CPI or whatever measure of inflation, the conception of time gets lost in the usual year-to-year figures. In other words, though the CPI even if meaningfully different at 1.46% in September is still only 1.43% higher than September 2014. Historically, whenever inflation falls so low it follows that up the next year with a robust turnaround. The current case is even more extreme given that inflation has rarely ever been as low as 2015 in the post-war era. To see but at best questionable acceleration this year following the historic lows last year is itself the most significant aspect – languishing.

That is why when you review inflation whether the CPI or the PCE Deflator you rarely find a 2-year rate so low as now.

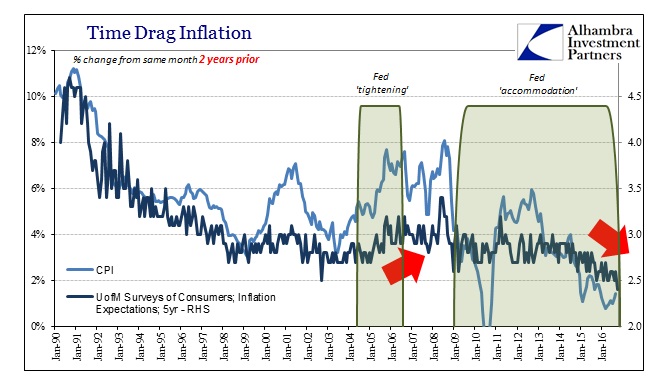

To emphasize how important time is with this highly unusual behavior, as noted recently other measures of inflation expectations including consumer surveys have fallen off this year. The University of Michigan’s inflation surveys, for example, provide an element of depth to how contrary inflation over time may affect economic conditions including consumer behavior.

The 5-year outlook for inflation throughout the 1990’s matched quite well this longer view of the CPI (2-year change). The rise in the CPI at the end of century didn’t much register in the UofM estimates, matching what Fed officials believe of inflation expectations being anchored to hugely positive perceptions about monetary policy and the ability of central bankers to deal with any stray conditions quickly and in good order. It does seem as if by 2000, people really expected that though inflation seemed a little high by 1990’s standards, it was no problem at all for the “maestro.”

That changed more than a little by the middle 2000’s. By contrast, UofM finds rising inflation expectations by 2005 that match a rising and persistent CPI (and PCE Deflator) that defied the 2% target to the upside. We can’t know exactly why expectations became more “unanchored”, but there were a couple of very big problems related to monetary policy and what were surely growing if then quite incomplete questions about the “maestro.”

The first, obviously, was the dot-com bubble and then bust, an enormous blot on the record of the FOMC that was only made worse by the Fed’s official refusal to even acknowledge it was ever a bubble at all. Laypeople rightly questioned basic monetary sanity of such a stance when it was obvious that “something” was so highly imbalanced as to lead to an enormous 3-year bear market of truly frightening proportions (that even the FOMC contemplated could lead to 1930’s-style deflation). History rightfully points in the direction of money during such times.

The second powerful rebuke to the Fed’s reputation was the inflationary conditions that only seemed to worsen despite the “maestro’s” last futile act. The Greenspan Fed began to raise rates at the end of June 2004; the CPI, as PCE Deflator, seemed not to notice. The FOMC raised the federal funds target from 1% all the way to 5.25% across two years, and it didn’t register at all; inflation stayed above their target. This disparity does seem to have been incorporated into inflation expectations, as represented by the UofM survey, where consumers were becoming more dubious as to what the Fed actually could do.

Like that “rate hike” period, the current one is a contradiction in the opposite direction. No matter what “stimulus” or continued “accommodation”, consumers are once more getting the notion that the Fed doesn’t have much influence. Inflation will vary sometimes widely in the short run, perhaps as now, but overall it doesn’t look much like what Janet Yellen (or Stanley Fischer) says. Truly “transitory” declines for inflation would look like what it had always before; a sharp drop followed closely by a sharp if not sharper rise. This is nowhere to be found and the UofM data as well as market measures for future expectations have clearly noticed.

This is a riddle only to those who believe fully in the central bank myth. Alan Greenspan was never anything like a maestro; he was only astute enough to cultivate a cultish devotion of accidental benefit. In other words, he took credit for what the eurodollar system seemed to accomplish by way of a stable and growing (global) economy. Though he actually did very little, it seemed to many, post hoc ergo propter hoc, he was a genius. When forced, however, to actually demonstrate the Fed’s assumed power, starting in June 2004, he instead only confirmed that there was none (or very limited ability).

Though it wasn’t fully recognized at the time, doubts were at least seeded to more fully bloom with the Bernanke Fed’s continued failure starting in August 2007. The events of the “rising dollar” have served to crystallize what has been suggested for more than a decade; they really don’t know what they are doing.

Stanley Fischer has for a year and a half suggested that the US economy is “very close” to completing its recovery cycle. In inflation terms stripped of context, that may seem by the September 2016 CPI somewhat plausible since it is as close to 2% as it has been in nearly two years. The problem is, once again, those two years (and counting).

Stay In Touch