So how does it end? It’s the only question that matters, more so perhaps than asking when this “end” might occur. We see the “dollar” tanking currencies again, though mostly the majors this time, but currencies have tanked for as long as they have floated; and a great many before that time, too. Is there something different now that wasn’t a motivating factor, say, twenty-five years ago when the pound crashed?

We know full well that there is, and the difference is almost entirely how short the world became of “dollars” through the eurodollar system. The pound’s 1992 nightmare was more about Britain than global finance, especially since it had by that point become a fairly regular occurrence for the currency that once ruled the world. Just 16 years before, the United Kingdom had suffered the great indignity of being bailed out by the IMF in what was truly the final act of the co-reserve system.

From the early 1990’s on, “something” had changed. Even Alan Greenspan knew it, though he wasn’t clear on what “it” was. Remarking to his FOMC colleagues once more in June 2003, he declared the difference between the US and Japan in 1990 as one of a broader financial base:

GREENSPAN Yet they really have only one means of financial intermediation, which is commercial banking. But we demonstrated in 1990, when our banking system froze up, that there were alternate means of intermediation, which carried us through and enabled the economy to recover until the banking system came back. They don’t have that option. They have a broken banking system, and they are dealing with an economy without other essential financial intermediation. We’re going to learn a good deal about how that economy functions in the future. [emphasis added]

That last sentence is chilling; he was right about all of it, including that sentence. When faced with the S&L crisis toward the end of the 1980’s, the US economy did not devolve into a lost decade right then as Japan had. There were other outlets for “financial intermediation” that had formed in the decades before, and even though these evolutions had played a part in fomenting trouble for the S&L’s it was the emergence of shadow banking and really wholesale finance that “enabled the economy to recovery.” Greenspan was talking about the bond market, but even that workaround was at that time a good part due to the international bond market and the money of the eurodollar.

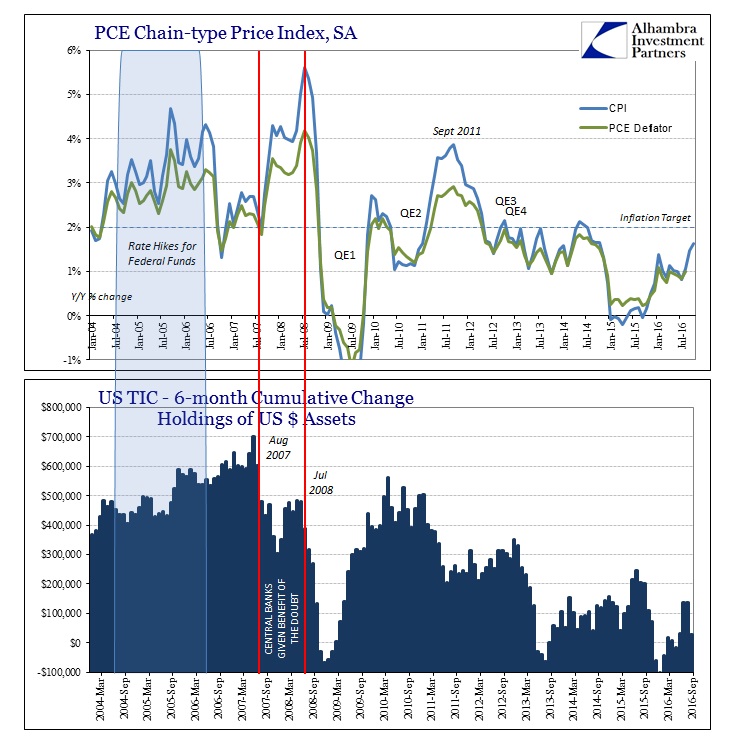

With global money growth in “dollars” at his back, Greenspan became a genius, the “maestro.” Unfortunately for his successor, the conditions of his spectacular reputation would be left for Bernanke to sort out (not that he didn’t do enough to deserve it; global savings glut nonsense and all). It started in the final acts of Greenspan’s tenure, where in June 2004 the FOMC sought to “tighten” by steadily raising the federal funds target rate but with little effect on inflation (or bonds). Given a more proper setting for money supply, such as the TIC data, we can easily observe why that was.

While monetary policy specifically applied to the federal funds market, thus by extension eurodollars at LIBOR, it wasn’t as universal a control mechanism as policymakers and even market agents had all assumed. The TIC figures show us an approximation for eurodollar expansion into overseas outlets, but that trend obviously applied in much broader fashion including domestic settings (housing bubble). As with other functional monetary equivalents, such as credit default swaps, the eurodollar system practically ignored the FOMC’s tightening directive, thus establishing what was really the marginal baseline for both financial as well as economic conditions.

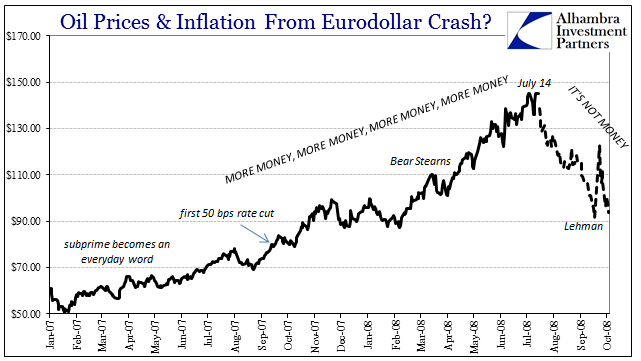

It wasn’t until August 2007 that things really got serious; when the eurodollar short truly turned “tight.” But, as you can see above, that led to a contradiction again, this time seemingly against eurodollar “supply” and back in favor of the FOMC. As the TIC figures show, global “dollar” conditions worsened dramatically, yet domestic inflation surged. The federal funds and eurodollar markets (LIBOR) fell into chaos, yet commodities and currencies signaled only further monetary growth.

The difference was perceptions about money that remained true to the Fed’s legend, and the lags of corrosive “dollar” conditions that allowed those perceptions to remain attached. The first emergency policy measure was undertaken in August 2007 where in an intermeeting conference call the FOMC voted to reduce the primary credit ceiling, what was once known as the Discount Rate. From that point forward, these markets operated under mistaken assumptions, that these new and more forceful monetary policies would be, eventually, too forceful and lead to inflation.

We also have to consider that throughout this period the crux of the liquidity turmoil was viewed as primarily foreign in nature, this time in Europe. While Bill Dudley expressed his shock at the size of the funding shortages from primarily European conduits, it was the first case of “their” problems staying over “there.” The combination led to what you see above, where global “dollars” quickly eroded in uneven fashion but not until summer 2008 did the whole system finally recoil (even Bear Stearns, a pretty good indicator that it wasn’t just an overseas problem, didn’t change perceptions about the FOMC and monetary policy, and largely because its forced merger was met with even newer and more exotic policy efforts).

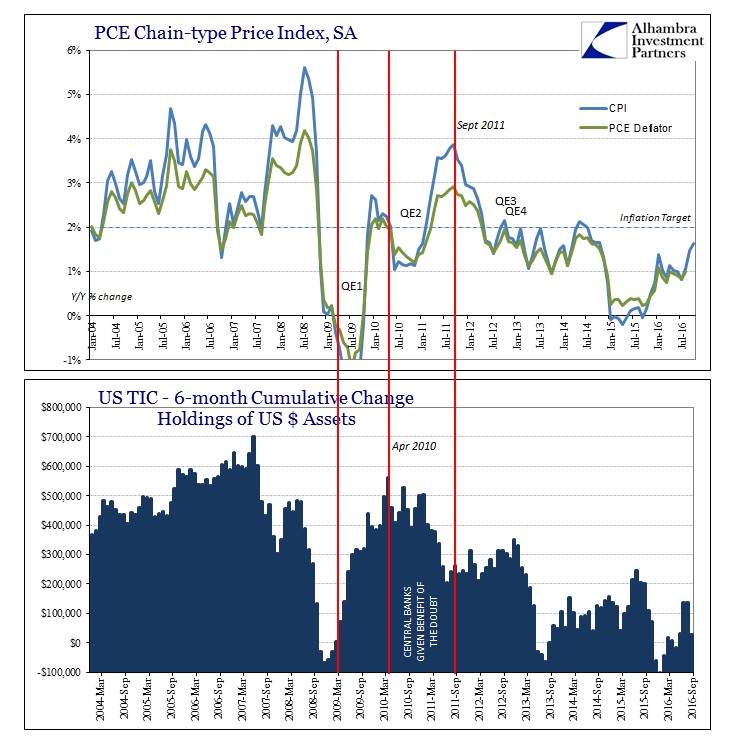

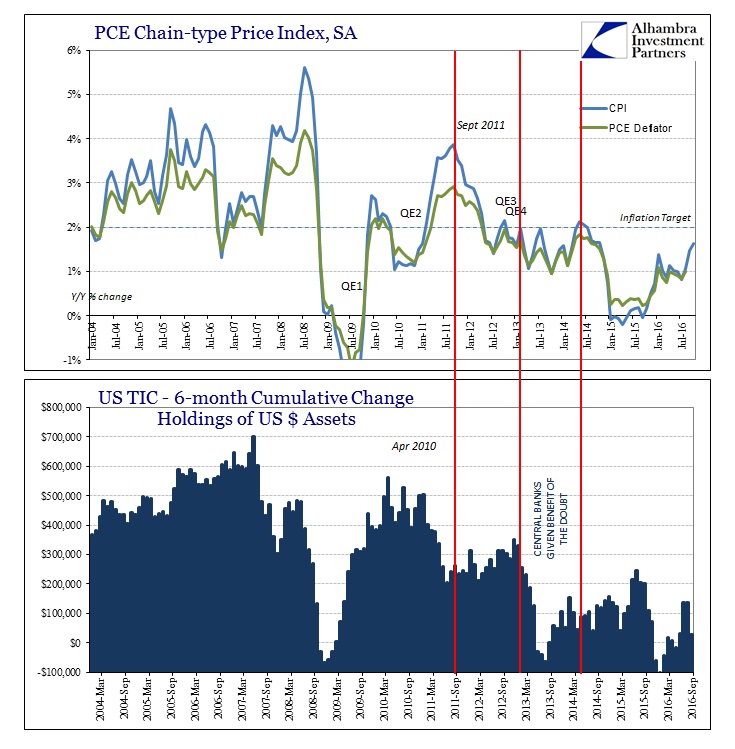

As strange as it sounds, this process repeated after the GFC, too. Policymakers have never accounted for the very different results from QE1 to QE2 to QE3 (and 4). The first seemed to work like a charm, as everything including inflation went back up again. The second was more mixed; the third barely registered. That would suggest, strongly, that it wasn’t those programs that determined their ultimate effectiveness.

This is not to say, however, that each weren’t initially received in the same ways. QE1 was believed a hugely positive influence, but was that the case or was it more so that the “dollar” supply itself was being restored. Perhaps QE1 had played a role in aiding that process, but as further examination shows quite clearly, quantitative easing was more of a background than determinant.

As in 2007, by early 2010 with sudden attention on Greece we find the TIC “dollar” proxy once more suggesting eroding global “dollar” conditions as if QE1 hadn’t happened. While that was met with a splash of mini-panic immediately (flash crash in stocks, interbank markets retrenched), the second QE (as well as other central bank interventions, such as those in Europe) in later 2010 was given the benefit of the doubt just like the emergency measures starting in August 2007. As you can see below, “dollars” were falling while inflation (and stocks) was still rising, the same exact divergence as before if not nearly as far or fast as in 2007/2008.

Also like 2007, it seemed far more that any problems in these complex financial arrangements were limited to strictly foreign concerns; the mainstream media talked about a European sovereign bond crisis that might have been a technically correct definition, but in more relevant terms was just another leg down for a return to the global “dollar” problem. As oil prices and thus global inflation shot up coincident with QE2 in the US and the European SMP, it was once more on the benefit of the doubt provided to global central banks doing what was believed to be something different.

By the middle of 2012, such optimism and sentiment had been wiped out again by the baseline of “dollars” (eurodollars, euroeuros, euroyen, eurofrancs, etc.). As the global economy responded with its usual lags, central banks acted yet again and were once more afforded the benefit of the doubt – but in much more subdued fashion, apart from stocks.

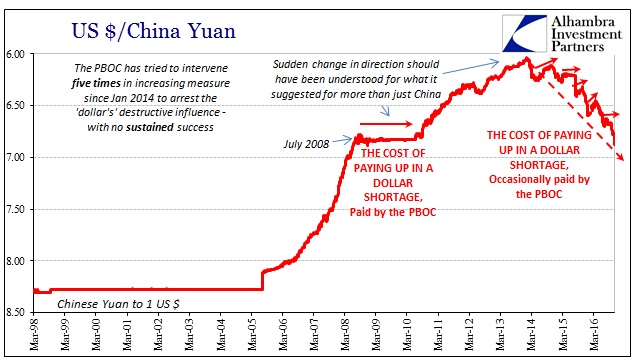

This time oil prices stabilized, but did not surge. Inflation rates followed oil prices and ticked below targets, as did global economic activity. By the middle of 2013, it was the same pattern being repeated for a third time – “dollars” were becoming very short all over again, but that seemed to be once more, from the US or European perspective, completely abroad. Though oil and commodities were stable, or maybe because oil and commodities were stable, the burgeoning EM currency problem was ignored as an unrelated matter of no great concern to what was becoming the global recovery and “liftoff” narrative. Here was optimism; there was growing turmoil.

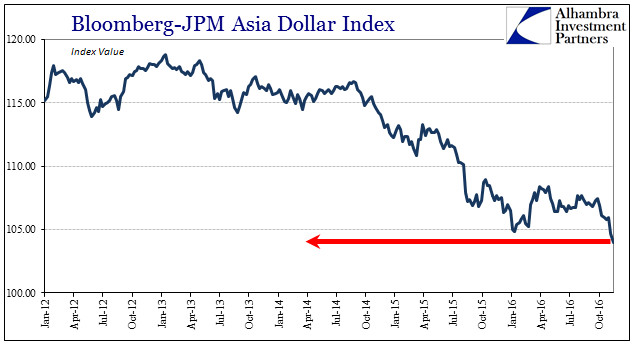

The monetary setting for 2014 was made by the events of 2013, a fact easily established by CNY almost as soon as the year started. It had stopped its almost decade-long ascent and started to reverse so dramatically that nobody quite knew what to make of it. It was believed, as this repeating pattern had established, an outcome for the Chinese alone to consider, another of the constant “war on speculators” that is mainstream shorthand for “we don’t understand.” It was, I think, a very good way to frame the turning point in 2014 as a huge chasm in economic expectations vs. the huge and gathering “dollar” problem that those economic expectations for a third time deemed irrelevant.

CNY wasn’t considered because QE3 was believed, for more than a year, different than QE2 or QE1 or the lowered Discount Rate and whatever else didn’t prevent the impossible panic in 2008. And yet, all over again, by August 2015 at least, the “dollar” proved for a third time to be the only thing that mattered. The “rising dollar” didn’t come from nowhere.

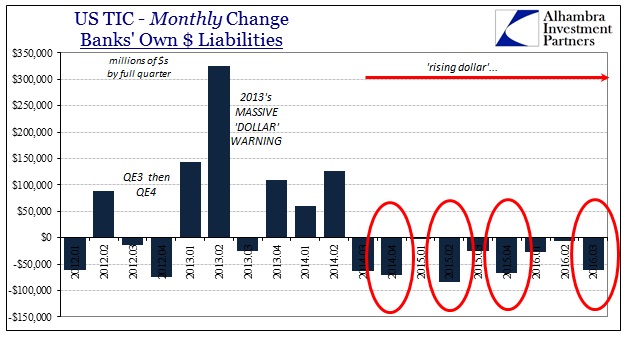

The size of the hole as represented in the TIC data for the middle of 2013 indicated about what to expect for the coming period, this “rising dollar.” I wrote in August 2013 coincident to the release of TIC covering the month of huge bond/MBS selloff:

The result is exactly what we have been preaching – a massive dollar squeeze that is starting to come out in the open. There is very little ambiguity out of the TIC data for June (just released)…

This is a tremendous warning that all is not well in the global banking system. The synthetic dollar short that plagued the global asset markets starting in August 2007, creating the conditions for panic, has re-emerged in a state of stress once again.

While the mainstream of economists and policymakers fell increasingly in love with the unemployment rate and Establishment Series labor stats, there was finally China being captured by the shortage that was all out in the open. It was a huge development that suggested the scale of what was going on in “dollar” places, an increasingly desperate plight of Chinese banks (including the PBOC). Because of the massive “dollar” warning in 2013, just a few months later in March 2014 the action for CNY wasn’t at all so confusing as it was made out to be:

In the Journal’s formulation, the PBOC is directing affairs, sending out ‘instructions’ that Chinese banks should ‘aggressively purchase dollars’ ostensibly to punish those hot money speculators. Given what we know of copper and dollar financing in general, is that really the case? Is it not more likely that the PBOC has lost control of dollar conditions and was forced by the ‘market’ to widen the daily band in order for dollar-starved banks to aggressively bid for dollars they could not otherwise obtain?

Someone once said or wrote that we are doomed to repeat history because no one was listening the first time. That sentiment is usually expressed with regard to much longer periods of time, but it applies here nonetheless. We are repeating history every few years because nobody was really listening the first time, or the second, or the third, and now, maybe, a fourth.

In what might be disappointing given all that, I can’t really say how this all ends. I still believe, strongly, that it does, perhaps has to end in a systemic reset, but what that ultimately looks like depends upon the amount of time it takes for the increasingly unstable system to force an equal response. That could mean a crash, a total disruption in social functions (overseas, of course), or just a whimper as some people in positions of power finally “get it” and realize everything about “dollars” above BLS stats. Ultimately, the manner of the reset will probably be driven by the amount of time it takes for that to happen. From what we can more easily surmise from the very recognizable repetitions shown here, until that point we should expect these reducing cycles to at least continue repeating their fluctuations between optimism (it’s all overseas! The Fed did something different!) and reality (“dollar”).

That is about the only thing we do know; unfortunately, reality hasn’t changed.

Stay In Touch