When Ben Bernanke sat down with 60 Minutes for an interview in March 2009, it was then the first time in 20 years a sitting Federal Reserve Chairman had appeared on TV one on one. The timing was not coincidental, as right at that moment the whole world appeared to be falling apart. Nevermind that Bernanke had up to that point declared great calamity impossible, he was looking to assure the masses that they would get it right thereafter, and really that there would be something left to get right.

That interview has become famous, or rather infamous, for introducing Americans to “green shoots.” Bernanke had not been the first to use the phrase, as Baroness Shriti Vadera, a minister in the Brown government in the UK, had been asked about “green shoots” in January 2009 to much criticism and ridicule. She had only been talking about a single credit event, she explained, some unspecified firm obtaining funding which mere weeks before would have been, in her view, impossible.

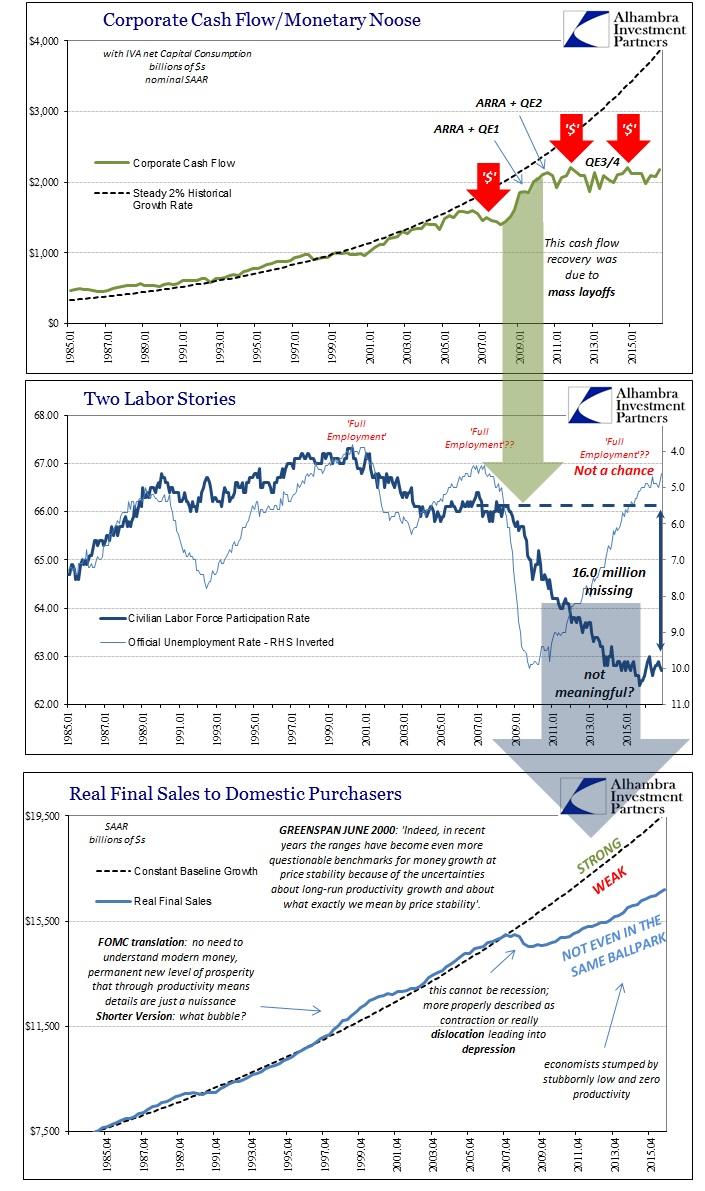

Chairman Bernanke was not so specific. He told Scott Pelley, “We’ll see recovery beginning next year, and it will pick up steam over time.” You could argue that he was just saying what he had to say; at that point what else could he say? The first part came technically true as the contraction did, in fact, end. It is the last part that we still struggle with, and though it has been rewritten lately there was then and for many years after no mistake about what all this rhetoric meant: it may take a while, but in the end the economy will be fully healed.

You would think if that started to happen, we wouldn’t need so much constant orotundity. But that is all that there has been to it. As late as February 2014, for example, a year and a half after Bernanke’s third attempt at QE “fertilizing”, San Francisco Fed President John Williams confidently proclaimed amidst the suddenly relevant cold and snow of the Polar Vortex that the economy was “on really solid footing.” I suppose at that late date using “green shoots” all over again would have given away the game, as even the most uninterested layperson would have asked themselves why what were called “green shoots” in March 2009 were not almost five years later harvestable.

It has always been this way. Economists talking about recovery are forced into just these kinds of soft non-specifics. A true recovery needs no actual prodding, no innuendo or nebulous bombast. Aside from the dubious unemployment rate, there just isn’t anything concrete. And we know because the unemployment rate is so often deployed with these empty rhetorical devices, that it, too, isn’t what it should be.

Speaking to a Mid-year Commencement at the University of Baltimore yesterday, current Fed Chairman Janet Yellen hit all those same platitudes, though with some very important between-the-lines variations.

The short version of what I have to say is that while I expect workers will continue to face some challenges in the coming years, I believe, for two reasons, that the job prospects and career opportunities for new graduates at this time are very good. First, after years of a slow economic recovery, you are entering the strongest job market in nearly a decade. The unemployment rate, at 4.6 percent, is near what it was before the recession. This is a level that has been associated with good job opportunities.

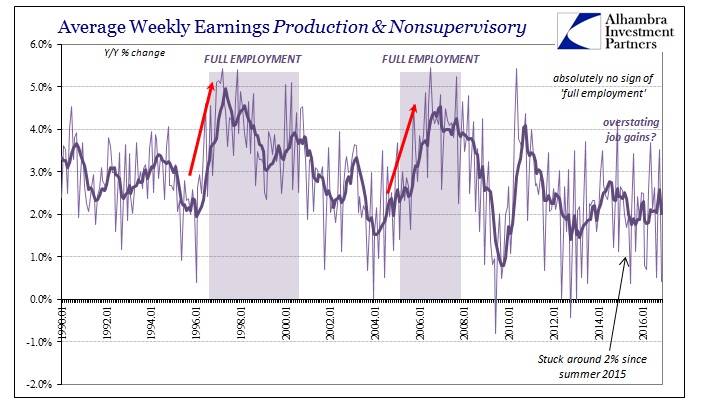

Her trick of semantics starts within the last sentence of the quoted passage: “has been.” In other words, it is absolutely true that in the past a 4.6% unemployment rate corresponded with only the best of times. What she hopes is the same as what Bernanke hoped for his “green shoots”; that everyone will just think positively about correlations with past circumstances and look beyond all the ways in which this time is, was, and has been consistently different.

She does attempt an answer for that blank space, however, though it comes in the same format of mere clues.

There are also indications that wage growth is picking up, and weekly earnings for younger workers have made strong gains over the past couple of years. That is probably one reason why younger workers reported feeling significantly more optimistic about the job market compared with 2013, according to a survey published just today by the Federal Reserve.

Indications? Why aren’t we so far past indications that words are no longer necessary at all? That’s the real thing about actual recoveries, nobody needs to be told it is happening. A recovery is a process that is obvious to all no matter how inattentive they might be. There is no need to survey today’s youth hoping desperately at some point before midlife to get out of their parents’ basements about the prospects of moving out of the basement because in a true recovery they are already moving or have moved out of them. Young adults would not need Federal Reserve researches to prod them into sensing the potential for positive attributes, just as whomever might be Fed Chair at that moment wouldn’t need to hint at “indications” of wage growth “picking up.”

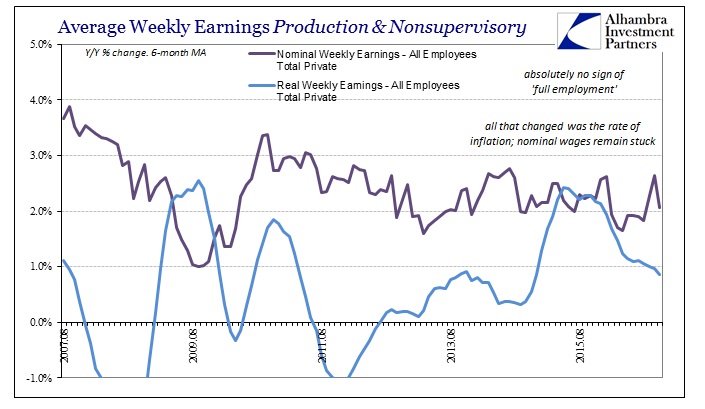

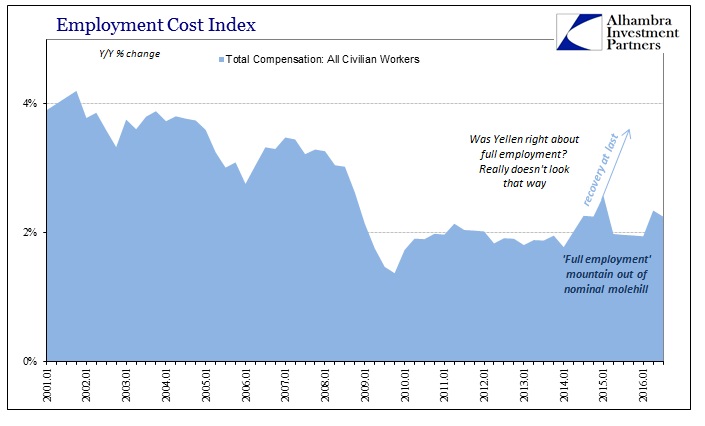

We have to ask “what are these “indications?”, for they are very difficult to find except in the colored interpretation of officials who have consistently so colored every bit of what has only been interpretation. As noted last week, Yellen in 2014 was actually specific about wages, a difference that can only be attributed to the fact that in that year economists and policymakers (redundant) really did believe, for the briefest moment, their own fantasies. Even though they were finally confident, they did know, as Yellen did, that wage growth was still only then “indicated.”

Yellen, to her credit, was outwardly far more cautious. In Congressional testimony also in May 2014, she noted that wages were rising but from a very low rate the year before and that the slow acceleration indicated a large amount of remaining “slack.” At that time Yellen said 3% to 4% for wage growth “would be normal.”

There is absolutely no intimation from a very broad survey of labor data that wages are about to rise now more than two years after that. Instead, wages have remained very much stuck, a fact that today’s youth are quite familiar with that perhaps those just now graduating might not yet be.

Janet Yellen, as all economists, has been seeing only signs of wage growth year after year, not actual wage growth which is the whole point. There is no magic switch by which an increasingly lost generation can expect a miracle of suddenly harvestable “green shoots.” There is only a history of failed past predictions about such things, of indications that truly didn’t indicate anything.

Yellen in yesterday’s speech wasn’t uniformly unrealistic, however. The only sentence truly worth quoting is the one that probably won’t ever be quoted.

The economy is growing more slowly than in past recoveries, and productivity growth, which is a major influence on wages, has been disappointing.

It’s an interesting if not totally contradictory assessment; she sees signs about wages even though the primary factor that determines wages “has been disappointing.” It’s an understandable understatement that basically amounts to the same revising of recovery down to an unrecognizable nub. Remember, she told those unfortunate students at the outset of her speech they were entering the “strongest job market in nearly a decade.” It’s not exactly the same robust endorsement as it sounds. Like “green shoots”, it basically says no more than that today is relatively better than 2008 and early 2009, the very bottom, such a low standard for comparison as to be an actual if backward admission of failure.

Business cycles are always judged peak to peak, as that is the only meaningful comparison. That Yellen is still asking for optimism based on “indications” of improvement relative to still the trough is all you need to know about these “rate hikes.” The economy isn’t ever going to recover, for economists, so the rest of us should be happy and accept whatever small positives might arise if indications are ever actually indicative.

Stay In Touch