When the FOMC first voted to taper QE, all the way back in late 2013, they did so because their modeled projections were pointing up in every way. Among the positive factors in those equations was fiscal policy that moving forward into 2014 would be far less of a “restraint.” It has been a big point of emphasis in monetary policy since the end of QE2. With QE3 and more fiscal activity, there could be no way 2014 and beyond would be anything other than full recovery. The FOMC even said so explicitly in their December 2013 meeting minutes.

The staff’s medium term forecast for real GDP growth was also revised up slightly, reflecting a small reduction in fiscal restraint from the recent federal budget agreement, which the staff assumed would be enacted; a lower anticipated trajectory for longer-term interest rates; and higher paths for equity values and home prices. Those factors, in total, more than offset a higher path for the foreign exchange value of the dollar. The staff continued to project that real GDP would expand more quickly over the next few years than it has this year and would rise significantly faster than the growth rate of potential output. This acceleration in economic activity was expected to be supported by an easing in the effects of fiscal policy restraint on economic growth, increases in consumer and business sentiment, continued improvements in credit availability and financial conditions, a further easing of the economic stresses in Europe, and still-accommodative monetary policy. [emphasis added]

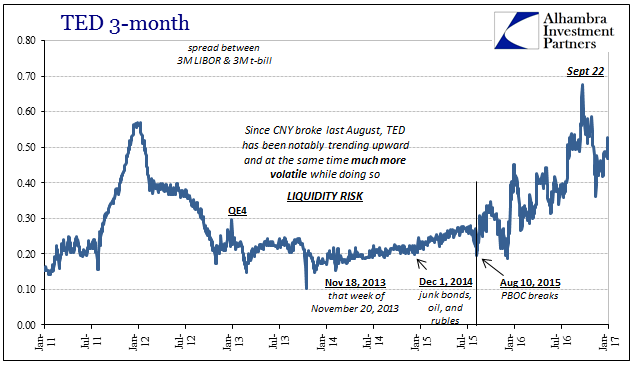

I particularly like their claim that the economy would be so strong going forward that it would “more than offset a higher path for the foreign exchange value of the dollar.” Clearly, they did not understand what the “rising dollar” meant, or even what it really was. If they had, as was being displayed all throughout the second half of 2013, they would have been far less self-assured.

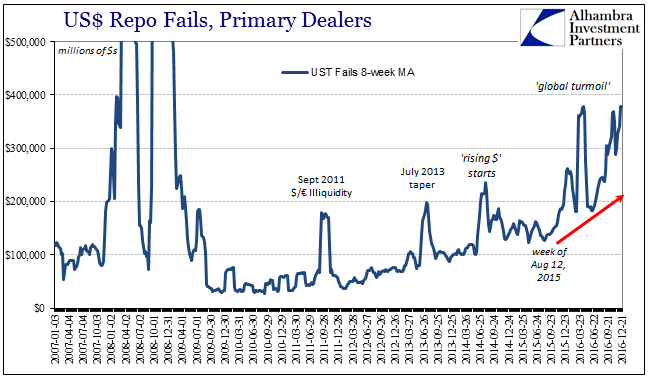

The confidence exhibited in that statement was emblematic of that “reflation” period, though at the time of the FOMC vote it was already close to its end, not its beginning. Eurdollar futures had turned all the way back at the start of September 2013, while the UST yield curve had for a month by then been compressing all over again. Even as credit and funding markets continued to move against the stated recovery, the paragraph quoted above would remain the baseline mainstream assumption well past 2014 when the “rising dollar” issued warning after warning to rethink the whole dollar paradigm.

In fact, economists and policymakers would not let go of that December 2013 statement until some unspecified date in the middle of 2016. It would take a near recession in the US, one that appeared despite the lack of completed recovery, as well as “global turmoil” that was an obvious relation to the “dollar” that US central bank officials clearly don’t know much about.

The FOMC vote last year to raise the federal funds target range (corridor, loosely speaking) was the last necessary (apparently) and emphatic emphasis for “they really don’t know what they are doing.”

Having gone through such a thorough discrediting, the Committee is this year comparably more subdued in its assessment this time around. As I have written all throughout the last half of last year, policymakers surely realize they screwed up. The December 2016 statement reflects this post-QE reduction.

Real GDP growth in the second half of 2016 was still expected to be faster than in the first half. The staff’s forecast for real GDP growth over the next several years was slightly higher, on balance, largely reflecting the effects of the staff’s provisional assumption that fiscal policy would be more expansionary in the coming years…The staff projected that real GDP would expand at a modestly faster pace than potential output in 2017 through 2019.

In December 2013, it was full recovery, or in the parlance of the orthodoxy, “significantly faster than the growth rate of potential output.” Three years and a “rising dollar” later, it is now “a modestly faster pace than potential output.” That isn’t, however, the total degree of downgrade, as potential output itself has been seriously redefined to an altogether different state.

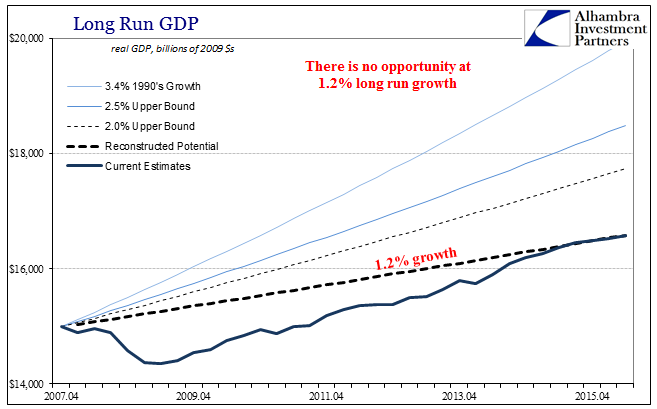

In late 2013, the Fed’s models told them that potential output, or the long run tendency for real GDP, was between 2.2% and 2.5%. That was already shaved from the 2.5% to 2.8% that was standard suggestion. By December 2016, the long run tendency for real GDP growth had been pared still further, to just 1.8% to 2.0%. Thus, recovery for taper in December 2013 was “significantly faster” than 2.2% to 2.5%, whereas in December 2016 it is “modestly faster” than 1.8% to 2.0%.

These changes may sound like small difference, but in their cumulative effects they are enormous – especially since the current trajectory for real GDP is barely 1.2%. It is yet another way of confirming that the FOMC no longer sees a recovery, but has instead found out the hard way there is “something” wrong with the US and global economy. They have not yet hit upon the cause, preferring to demure and digress into Baby Boomer retirement or some mysterious skills mismatch among US workers that wasn’t a problem until the second half of 2008 – and then, supposedly, was a problem all at once.

The FOMC minutes for this latest meeting do show some growth and resemblance of scientific principles. Though not close to a full reckoning, it is in sharp contrast to what was recorded for December 2013 and shows quite well this forced evolution in policy thinking. The relevant contention was included in the middle of the quote above, nestled right at the ellipsis in that passage. Why is the FOMC three years late so much more reserved in their overall forecast?

These effects were substantially counterbalanced by the restraint from the higher assumed paths for longer-term interest rates and the foreign exchange value of the dollar.

They don’t know what it truly is or why, but they have learned (again, the hard way) that it isn’t good and it matters perhaps more than anything else. Not even the Trump-euphoria about the looming fiscal “stimulus” is so unqualified like it was for what were really just minor fiscal adjustments in 2013 moving forward.

The risks to the forecast for real GDP were seen as tilted to the downside, reflecting the staff’s assessment that monetary policy appeared to be better positioned to offset large positive shocks than substantial adverse ones.

And:

Among the downside risks cited were the possibility of additional appreciation of the foreign exchange value of the dollar, financial vulnerabilities in some foreign economies, and the proximity of the federal funds rate to the effective lower bound… For some participants, the greater upside risks to economic growth, the upward movement in inflation compensation over recent months, or the possibility of further increases in oil prices had increased the upside risks to their inflation forecasts. However, several others pointed out that a further rise in the dollar might continue to hold down inflation.

If you knew nothing else about the economy the last few years other than these two FOMC statements and evaluations, you would be forced to conclude that the dollar has been judged much, much more of an issue now. No kidding.

Stay In Touch