In addition to all the myriad indications of a serious labor market slowdown last year, despite the fact that the unemployment rate has been 5% or less since September 2015, and in all likelihood was that again in January, there is no indication of any acceleration in wages or earnings. None. The labor market just is not as it is described in the mainstream. For years, we have been told just how robust it has been, and would therefore provide a foundation against economic weakness in the form of a “rising dollar” that economists didn’t and don’t understand.

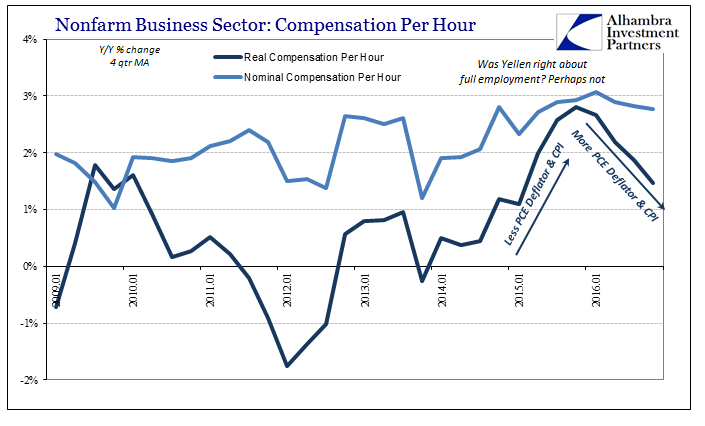

Real hourly compensation in Q4 was estimated to have grown by just 1.1% year-over-year, and in the quarterly comparison was actually negative to Q3, the second such quarterly contraction in 2016. The reason for that is simply oil prices, meaning the CPI. A rising CPI due entirely to the commodity rebound is not indicative of true reflation or growth, and thus acts as a further depressant. Nominally, wages and compensation remain as stuck as ever, having never been able to burst toward historical recovery growth the entire “recovery” period.

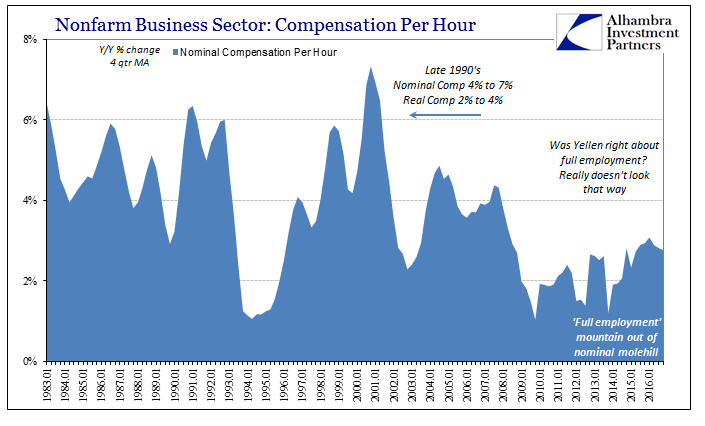

The clear determination against “full employment” is truly made by the historical context of this data series.

In this way, the estimates for compensation per hour actually match the trajectory of the labor force since 2007. There are fewer officially counted workers and prospective workers, proportional to the population, so it would stand to reason that the unemployment rate does not describe the full economy. For several years in a row, the FOMC and economists have been predicting an end to “slack” as a nod to the unemployment rate, and yet month after month, quarter after quarter, year after year there isn’t the slightest indication that is right. Fewer utilized workers would explain quite well lower overall and sustained wage and compensation increases.

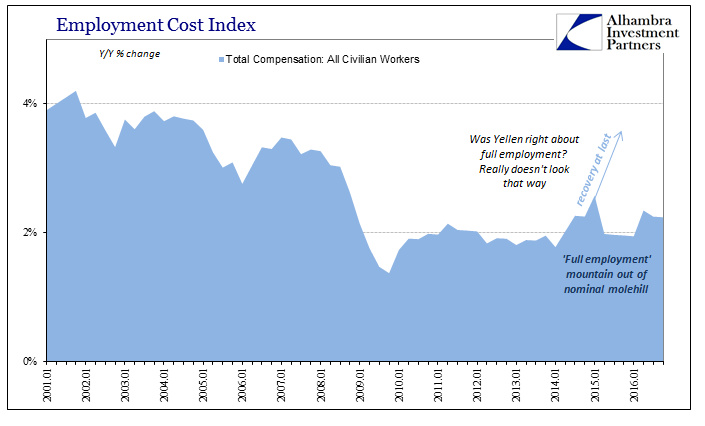

The Employment Cost Index which measures benefits as well as cash compensation confirms this is not simply related to one side or the other, as it, too, remains as it has throughout the aftermath of the Great “Recession.” Despite repeated expectations at each small upward gyration that was sure to be the start of the inflationary acceleration of actual recovery and sustainable growth there has only been repeated though not really “unexpected” disappointment.

The Fed still, to this day, talks about “solid” labor or job gains, which is only true if you reclassify sluggish as solid, justified by the very low standard that at least it isn’t worse. It is the realization of the difference between positive numbers and meaningful advance, a distinction that after so much time is now being more appreciated in widespread fashion. That is what “stimulus” has become, and it is a warning for anyone infatuated with the renewed idea for more of it in whatever form.

Stay In Touch