Janet Yellen was apparently “hawkish” again in her latest speech, though the reasons why she may have been continue to elude the media and many markets. In many ways, she doesn’t even know, a fact that she expressed several months ago to likewise very little appreciation. The FOMC may or may not raise rates in the next meeting or the next several meetings, but if they do it doesn’t mean anything like how it continues to be described. There truly is no reason for this misleading interpretation, as all the data is readily available to completely dispel it.

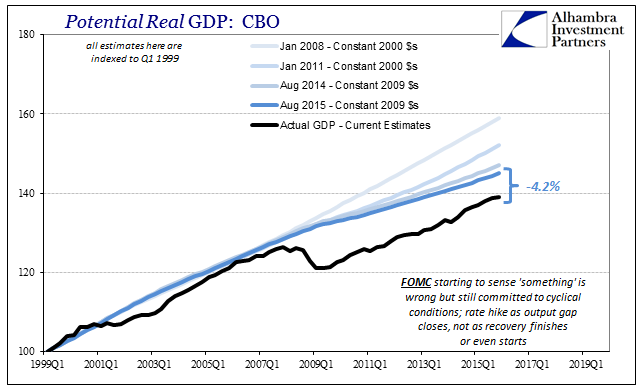

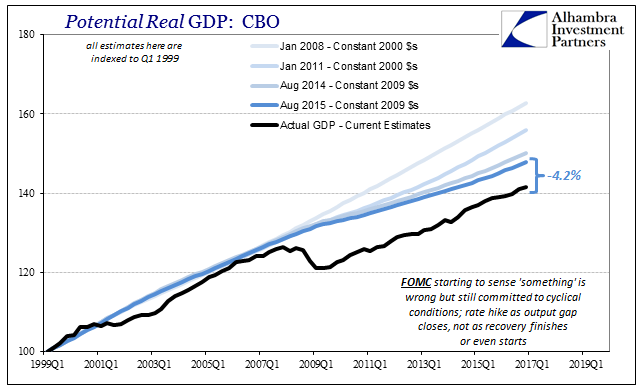

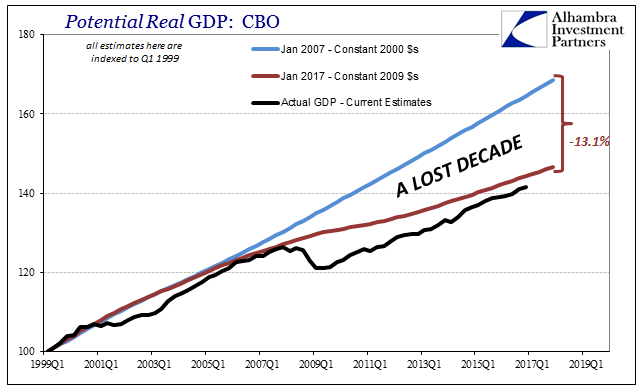

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO), for example, produces estimates for economic potential on a semi-annual basis. This doesn’t mean they know what our economy’s potential is or might be, but the figures have other uses. The manner in which they are derived is entirely similar with the models and assumptions used by the Federal Reserve (that does not publish estimates for potential). Economic potential is a key concept in monetary policy, perhaps even the most important part of it.

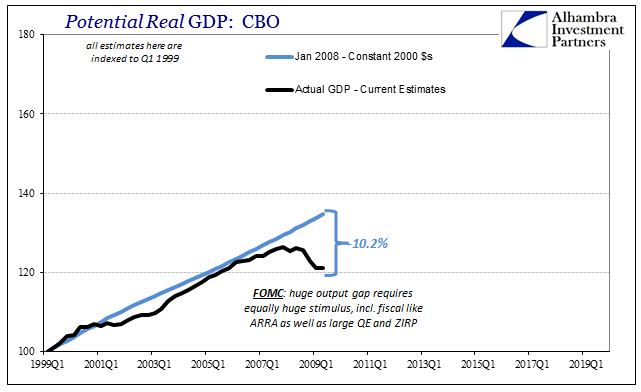

The whole of any “stimulus” regime is predicated upon an estimation of the output gap. This is nothing more than the difference between potential and actual output. A recession is a large positive gap, and therefore in orthodox terms “requires” an equally large response. When economists (really Economists) proposed first ZIRP and QE, as well as the ARRA, they did so because real GDP at the time was sharply lower than their estimates for economic potential. In short, the Great “Recession” was at the time believed to be a large recession.

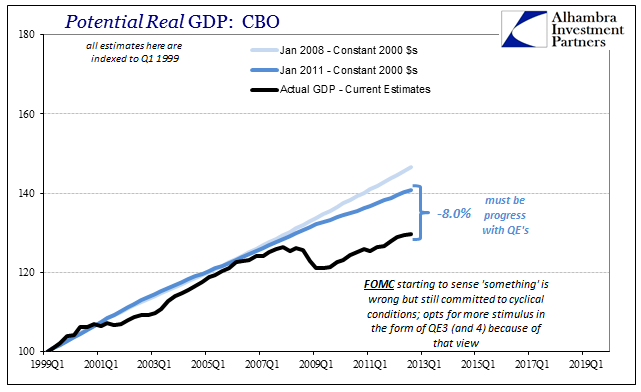

Using the CBO estimates in time we see that did seem to be the case. By the trough of the Great “Recession” real GDP was about 10% below (using the latest GDP figures) the pre-crisis (January 2008) CBO baseline for potential. Such a large output gap (which was underestimated at first) justified an equally large “stimulus” response. The whole point of quantitative easing is predicated on this calculation first, where the “Q” refers to the exact size of the gap and the precise amount of LSAP’s needed to close it.

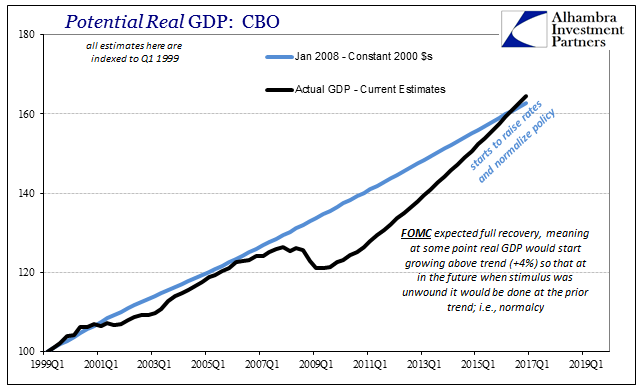

What the FOMC fully expected was full recovery, as did all (almost) Americans and the rest of the world. To the their limited credit, policymakers did note contemporarily that there were still lingering issues to be overcome, meaning that the recovery while full would take longer to achieve. As such, they expected real GDP at some point to ignite toward 4% or more in sustained fashion so that by several years past that trigger normalcy would be achieved, greatly aided by all the “stimulus.”

A slow recovery, however, is one fraught with dangers. Sluggishness due to what was thought nothing more than a debt overhang increases possible missteps. Those first appeared very early on in the “recovery cycle” so that by only its second year the FOMC felt compelled to introduce a second QE.

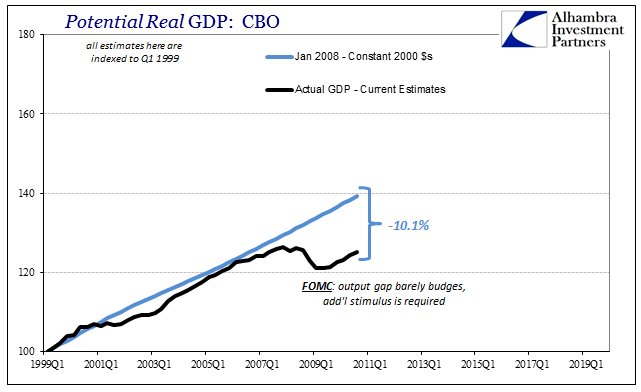

It was easy enough to blame Greece for this, as the output gap had barely changed despite a year and a half of ZIRP and QE1. We know via the 2011 FOMC transcripts that despite the emergence of what became a near-recession starting in 2011 the Committee did not then attribute it to anything apart from “transitory” factors, citing still a cyclical condition. They were starting to consider structural issues, largely related to labor, and at that time they were more concerned about the long run problems with long-term unemployment as a primary defect.

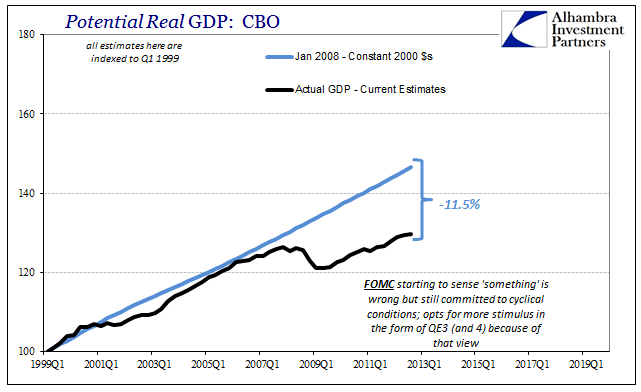

By the time they debated QE3 in September 2012, the output gap by the CBO’s estimation of its January 2008 baseline had actually increased. To Economists, this just wasn’t possible especially given two QE’s and by then almost four years of ZIRP. Again, it was easy to assign a European cause, but that wouldn’t account for the lack of policy progress in closing the output gap at least somewhat.

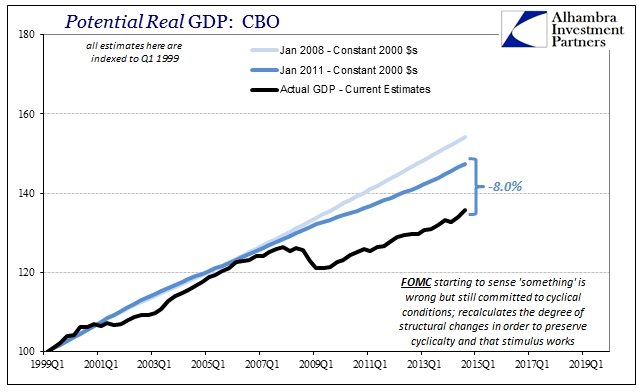

Instead, the CBO, as FOMC, was forced to reconsider these trend issues though only mildly at first. In other words, using the updated CBO trend baseline shows that the output gap did close, only that it did so from above rather than from below.

To policymakers, this made more sense given that they believed without qualification “stimulus” actually stimulated. If it didn’t show up in the output gap calculated from the prior baseline, then it had to be because the prior baseline assumptions were incomplete. Despite that troubling introduction, even by 2013 and 2014 still Economists were talking cycle not demographics. As noted last week, in February 2013 Janet Yellen stated as much:

This question is frequently discussed by the FOMC. I cannot speak for the Committee or my colleagues, some of whom have publicly related their own conclusions on this topic. However, I see the evidence as consistent with the view that the increase in unemployment since the onset of the Great Recession has been largely cyclical and not structural.

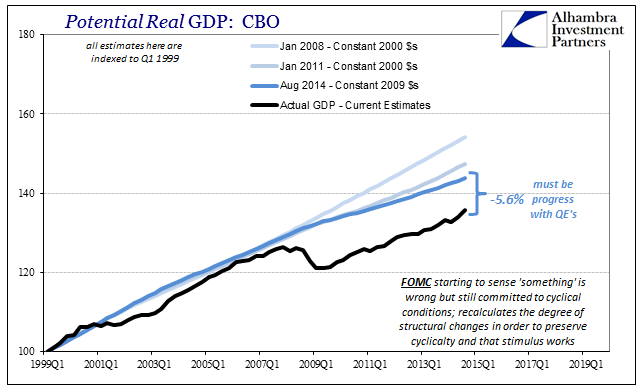

And yet, even by the solid growth quarters (in terms of GDP) in the middle of 2014, the two that convinced both policymakers and the mainstream that recovery was at hand, there was still no progress in closing the output gap as indicated by prior estimates. In fact, to those older potential baselines the economy was getting further away from what used to be agreed upon as a healthy one.

When the Fed debated QE3 in 2012, the gap was 8% to the January 2011 calculation for potential, and when the Fed went into “exit” mode at the end of 2014 after those two seemingly compelling quarters the output gap to the same baseline was still 8%. But, structural issues even if held in the background changed the nature of the decision point. The updated trend estimates showed that the output gap was closing but in the same manner as before, from above (reduced trend) rather than from below (recovery).

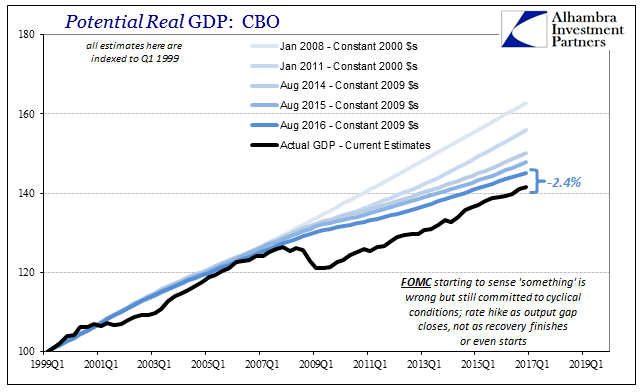

Even by the time the FOMC voted for the first rate hike (RHINO) in December 2015, they did so because once more the trend was lowered.

The output gap to the prior August 2014 baseline had also barely budged, but more severe reductions in trend in an odd and counterintuitive way made it more than sufficient for a rate hike. The mainstream interpreted it as recovery, when in fact it was confirmation that there would never be one.

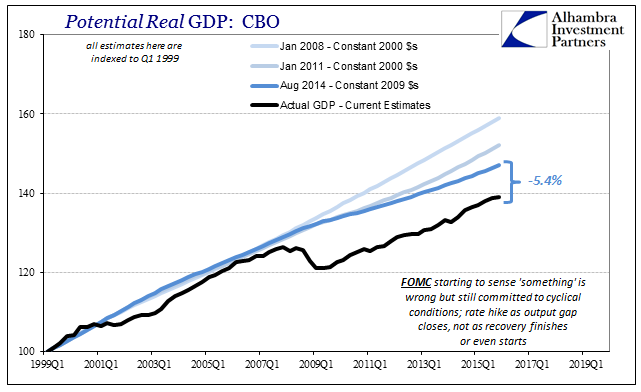

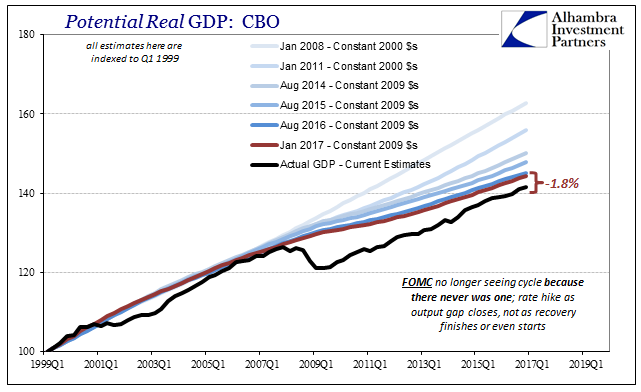

That point was simply driven all the way home in 2016. The difference between August 2015 estimates for trend and those from August 2016 were appropriately large given all that had happened in between. By that time, policymakers were no longer considering cyclicality in their policy discussions. It has entirely moved to trend, especially now that the cumulative reductions have all but closed the output gap.

Again, the CBO estimates are derived from largely the same assumptions as well as much the same data, but we don’t know exactly what the Fed’s estimates are. They may have an even lower trend estimate, meaning an output gap that has more completely been erased. Therefore, no matter what the actual economic conditions today, they would “raise rates” anyway because that is how orthodox policy is set.

That may actually be the case, as the latest update (January 2017) from the CBO reduces the trendline for potential still further, lower than even at the last benchmark in August 2016.

What that means is that this entire time the output gap has been closed exclusively by redrawing economic potential and none from QE or ZIRP. Since this entire discussion takes place in orthodox terms and upon orthodox principles, it is completely unsurprising policy assumptions and its outlook have evolved in the same manner; reaching last year a point where not just QE but “accommodation” of any kind is to authorities no longer warranted. The mainstream believes that this is because the economy is about to be healed when in fact, again, it is instead recognition from the official sector that it never will be.

By raising rates, and doing it again, the Federal Reserve has just endorsed a lost decade, and more importantly its continuation.

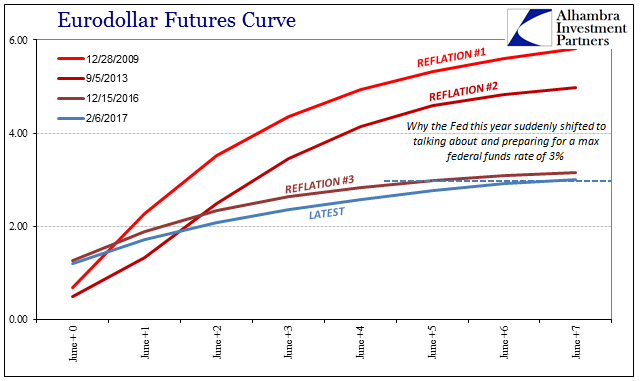

They don’t talk openly in these terms, of course, because they know the consequences of doing so. There would be far too many uncomfortable questions were an honest assessment ever given. So they have shifted to secular stagnation of Baby Boomer retirement and America’s drug addled labor force in order to introduce the subject. Translating them into monetary policy and orthodox economic terms, they speak of a lower R* that to them means the federal funds rate may never normalize, hoping that perhaps under the best of conditions it gets back to around 3% in several more years.

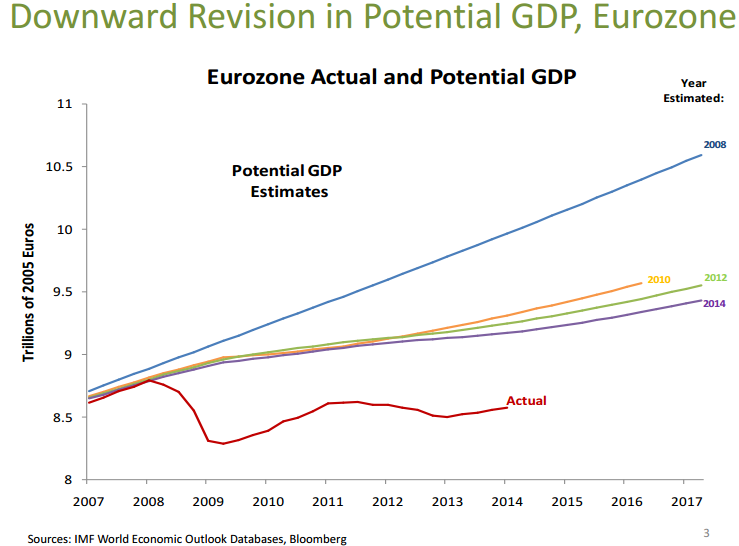

It is a gross dereliction of duty, especially where central bankers are now declaring both a deeply unsatisfactory and dangerous future as well as how that is the proper economic state. It is entirely nonsense, as the answer lies in the very place that central banks refuse to consider – the global money system. The results you see above are not unique to the United States, having been replicated all over the world. As discussed here, it is endemic in Europe as well, and can be spotted all over the emerging market world. There is nothing proper about it.

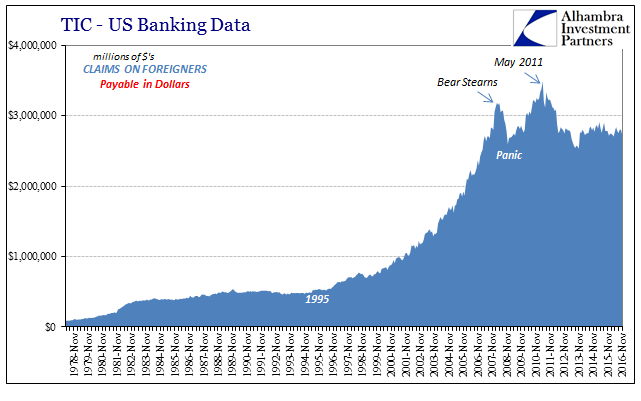

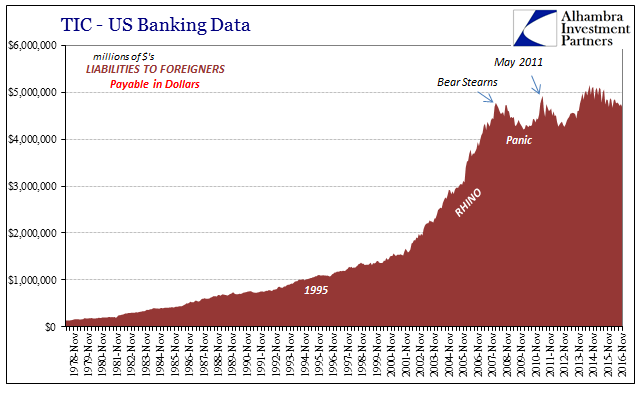

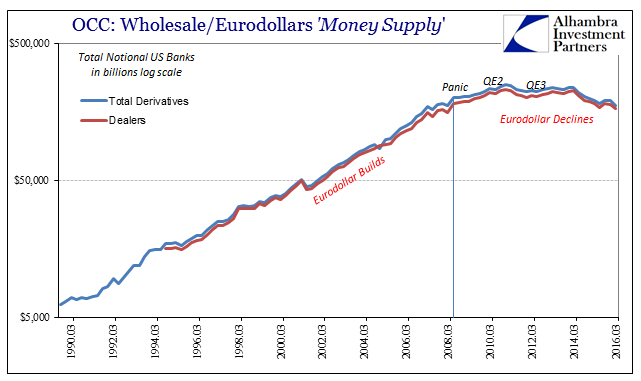

As further discussed yesterday, like the evolution of potential it’s not even difficult to see the cause. The world economy before the Great “Recession” built up on a credit-based money system. “Dollars” of all types, shapes, and sizes flew easily all around the world as banks grew in geometric fashion. Very simply, before 2008 there was sustained monetary growth; after, there has been no growth. Is it really surprising to find that there has been no economic growth, either?

Central banks will never make that connection because how can they? It would be confessing to, again, gross dereliction of duty. Because of that, they are left instead with only the absurd to explain why they kept expecting cyclical results only to find none. Sure, there are Baby Boomers who have retired, but the participation rate of those aged 55 and above has actually increased. There is also a serious drug problem in the US, but is that the cause of labor discrepancies or the effects of an economy cruelly stripped of all opportunity?

Like it or not, we are in a depression having lost already one decade to it. The Fed raising rates is a wholly disastrous outcome because it means officials will no longer even try to do anything about it! It’s not that we want them to do more QE or come up with the next useless program, rather we require at the very least an honest and open discussion about what happened and further why it was and is unacceptable.

Stay In Touch