Declines in several of the world’s PMI’s in April have furthered doubts about the global “reflation.” But while many disappointed, some sharply, it isn’t just this one month that has sown them. In China, for example, both the manufacturing and non-manufacturing sentiment indices declined to 6-month lows. While that might be erased next month as normal short run volatility, the indicators overall do seem to have stalled out during that time. What’s more intriguing is that they have done so at almost the same level as in 2014.

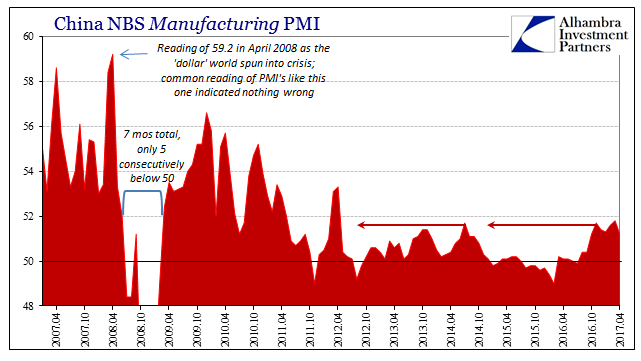

The NBS Manufacturing PMI for China dropped to 51.2 from 51.8 in March. That is roughly equivalent to where the index peaked three years ago. While the rise since hitting a low of 49 last February has been significant, it is nothing like what is being portrayed by the mainstream. Despite more than a year since that trough, there are only indications of a rebound like that prior one rather than those before 2012; hitting a ceiling near 52 is vastly different than one around 56 or even 58.

While there was some acceleration suggested toward the end of last year, by historical comparison it was conspicuously mild. That tempered enthusiasm is the dominant feature of these plus sides of the last six years dating back to the global turn in 2011. China’s manufacturing sector may not right now be getting worse, but it isn’t really getting better, either. The best description continues to be the one applied to inflation; meandering.

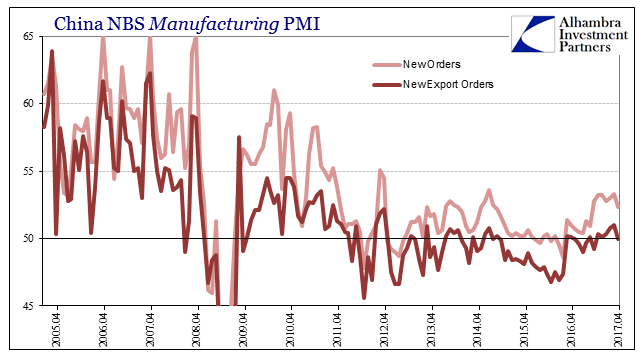

The subcomponents for new orders and new export orders demonstrate very well this subdued trend.

Again, they have stalled out at levels more like 2014 than 2007, therefore suggesting nothing has really changed in the Chinese or global economy. Whatever small improvements in comparison to early last year and “global turmoil” are being misconstrued as something they clearly are not – especially when you hear the levels of these PMI’s described as the highest in years, as they were for March 2017.

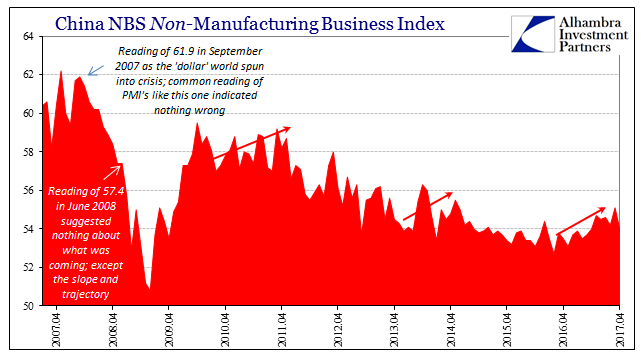

It was also true of China’s Non-Manufacturing PMI. It was last month the highest since 2014, but this month at 54 it is right back in the same woeful range and repeating, it appears, the same cycle of nowhere all over again.

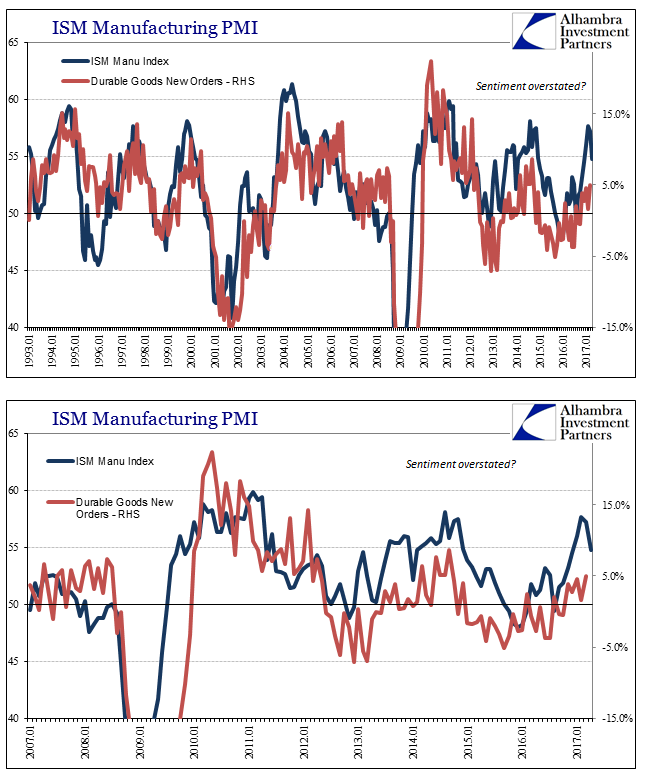

On this side of the Pacific, manufacturing sentiment fell back, too, only here there was far more enthusiasm to the point of euphoria. It was, as has been the case for the last six years, unbacked by anything other than inappropriate extrapolations. Like China, US conditions particularly in manufacturing are better this year, but that also means next to nothing here as there.

The ISM Manufacturing PMI surged to 57.7 in February, by far the highest level in years. Again, the repetition of sentiment cycles is very clear, only in the US it has deviated from underlying data to a much higher, more noticeable degree. It would suggest US manufacturers are overly optimistic whereas Chinese manufacturers appear more realistic by comparison.

The gap between sentiment and reality, as Q1 GDP demonstrated well, has closed somewhat more in the latest monthly report. The ISM index fell for a second month, down sharply in April 2017 by 2.4 points to 54.8. The new orders subindex fell 6 points, if from a high level in March.

By no means is this conclusive, but the combined picture of global manufacturing sentiment, anyway, is of a limited rebound that is all-too-familiar for the global economy. So far, it is an almost perfect copy of the 2013-14 period, where small improvements were then, too, blurred upward into big things that had no chance of happening. Maybe in China they have made peace with this economic condition overall, but over here there is an almost hazy cyclical disbelief to it. As I wrote Friday:

For most of us, this just cannot be; it cannot be possible that there is so little growth and opportunity after ten years of none. Even if predicated on just randomness alone, blind dumb luck, the economy should start to correct at some point. It just doesn’t seem believable that in the 21st century depression of this magnitude and length could happen.

And so the longer it goes on, people seem to believe the greater the chance that something just has to go right. It is a happy [and] comforting thought, aided in emotional manipulation by the constant mainstream optimism. In that belief, every minor uptick is extrapolated far beyond its true significance as that thing that will surely restore positive balance and order.

The mainstream reviews these PMI’s in comparison to last year and sees the upward trend and little else so as to be comforted by nothing more than the direction. It is more rational analysis that compares all these PMI’s to 2014 and appreciates the blatant similarities as testament to ongoing, chronic disorder. As Economists used to say, we see here nothing but continuing “headwinds.” The 2012 slowdown enters its sixth year on an upswing, but that does not indicate all that much as the overall condition has not been erased despite considerable (global) effort.

Stay In Touch