Consistent with the LMCI, the JOLTS data series suggests very little has changed. There are two crossover points between them, where the level of Hires and the Quits Rate (a calculation derived from the JOLTS estimates) are included as two of the 19 factors in the LMCI. Though the latter was revised somewhat higher over the past few months, it was not significant nor was it due to the updates to JOLTS.

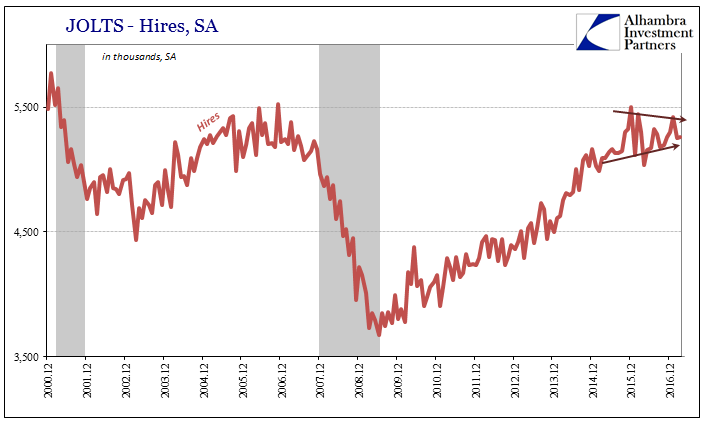

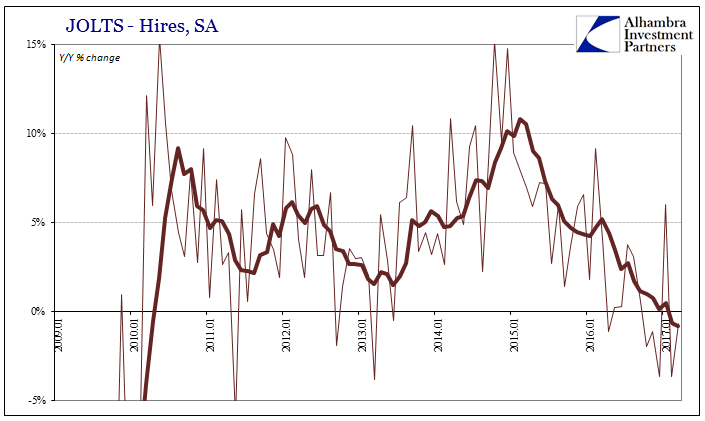

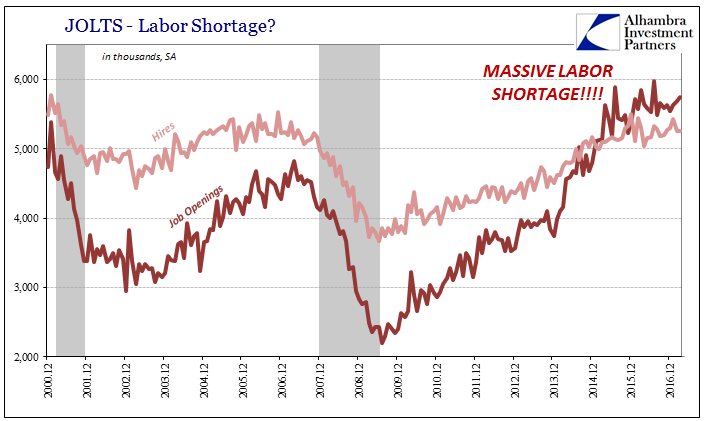

The level of Hires was figured to be 5.26 million in March 2017, just slightly more than the downwardly revised 5.25 million in February. Year-over-year, the pace of hiring activity is slightly less in 2017 than 2016, with small contraction indicated in five out of the last six months. As has consistently been the case, it is the absence of further momentum that stands out, leaving interpretation to define either a “full employment” plateau or something more like a sustained slowdown inside an overall shrunken economy.

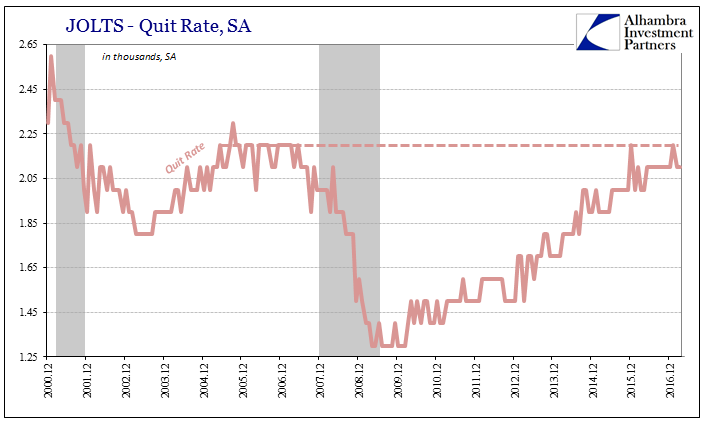

The Quits Rate largely indicates the same plateau. After reaching 2.0 for the first time in September 2014, it has largely moved sideways with only an occasional higher reading ever since. It has on two occasions, the last being January 2017, registered a rate of 2.2, equivalent to about where the labor market was during the prior business cycle peak.

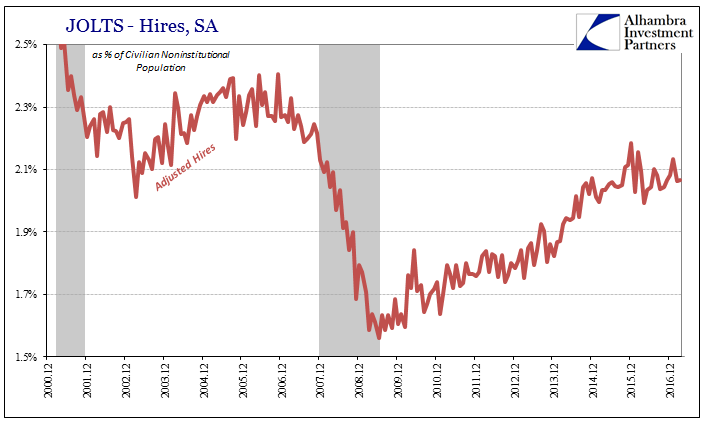

Both Hires as well as Quit Rate therefore suggest that according to this view of the labor market there remains some diminished capacity when compared to the pre-crisis era. That possibility becomes clear when adjusting the rate of Hires by population growth, presenting yet again the participation problem. If you believe opioids and Baby Boomers are holding back the labor market, then you also believe this is not an appropriate or useful modification.

But a great deal of the justification for that belief rests on more dubious evidence. Primarily, the contention is based on estimates of labor demand, and really only one data set that of JOLTS Job Openings. In 2014, those exploded higher while the rate of Hires increased more modestly. The difference between them, then, is proclaimed to be a product of “skills mismatch”, the polite version of the lazy, drug addicted, or retired American worker now widely theorized throughout Economics and the mainstream.

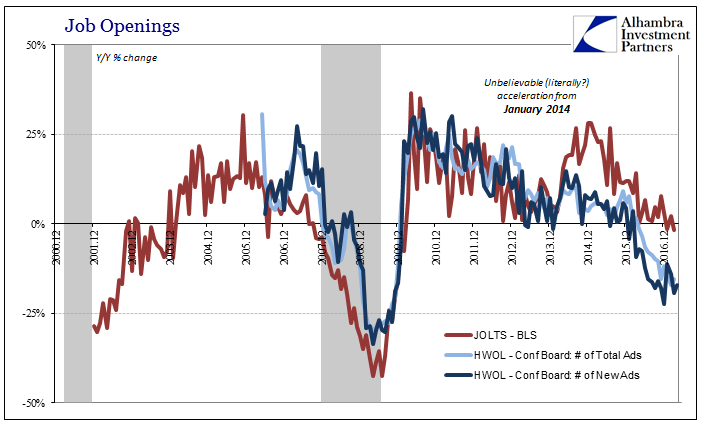

Yet, the Federal Reserve, whose members are some of the most prominent expounders of the muddy labor force theory, didn’t include Job Openings in its LMCI alternate measure. This is a curious omission given these circumstances, especially since alternate means of labor demand were used in it. There are two surveys from the NFIB included (Jobs Hard to Fill; Hiring Plans) but also a “composite help wanted index” derived from Conference Board data habituated by further “author calculations.”

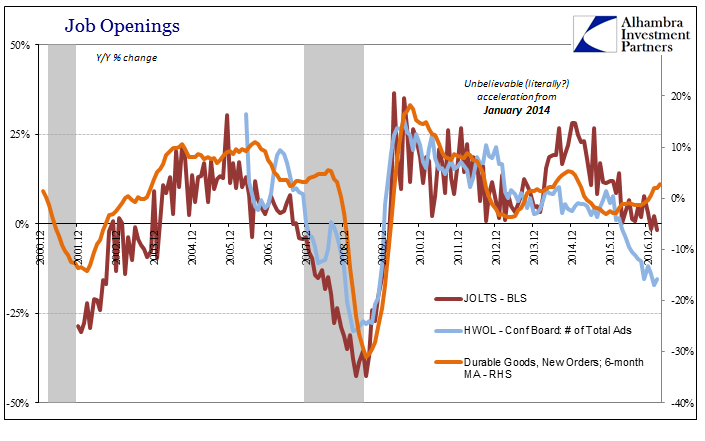

I have presented the Conference Board’s HWOL series for Job Openings before, and they show a much different trend for labor demand than does JOLTS. They both agree that whatever level of Job Openings across the US economy, it has cooled in recent years. What we don’t know is from what level, a pertinent question given the plateau in Hires as well as the Quit Rate.

The Conference Board claims that there may be problems with the methodology of its index due to changes in online employment ad conditions related to Craigslist. Even if that is the case, it doesn’t erase the vast, significant difference in trajectory of labor demand during 2014 that is at the heart of this issue.

Most other economic accounts produce a far more reserved “improvement” in 2014, more consistent with the 2012 slowdown economy globally. It suggests that Job Openings as estimated by the BLS in JOLTS inexplicably surged when nothing else did – including other estimates for Job Openings that actually were included, in part, within the Federal Reserve’s alternate labor measure. For 2017, the JOLTS version suggests that Job Openings are up somewhat, while the HWOL series claims they are not.

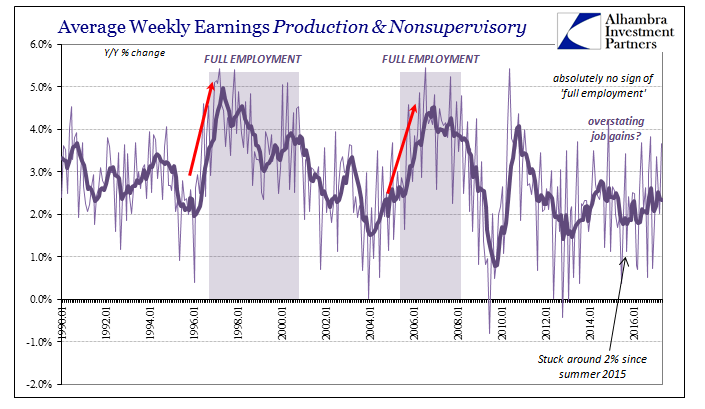

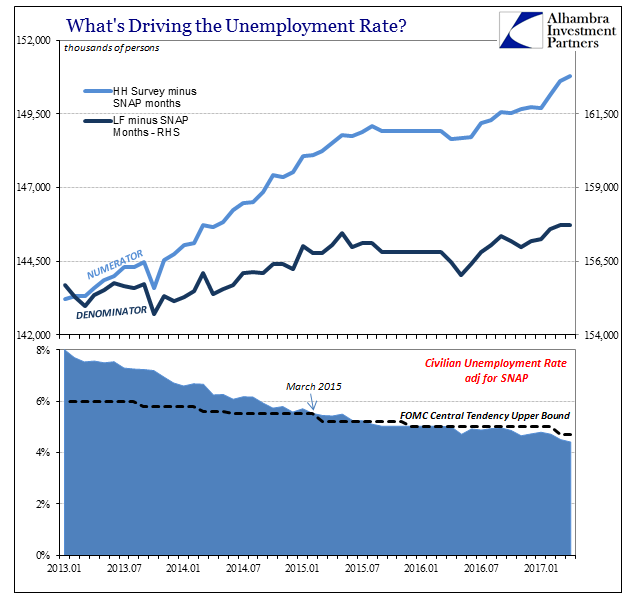

As has been the case throughout, the level of wage growth gives us the likely answer. If there is a plateau (or worse) in the labor market, it takes place not at or even near full employment but considerably short of it (slack). Once again the Fed’s very estimates point in that direction, where, as noted last Friday, their modeled view of the central tendency for full employment has followed the calculated unemployment rate lower – all because wage growth, therefore inflation remains just that elusive.

It further asserts a rational basis for the absence of economic momentum here as well as other places (like China) reliant on US consumers for the marginal direction of the economy. No labor, no income, no growth. A slowdown taking further part of a shrunken economy would be perfectly consistent with one that struggles with weak and uneven growth conditions. It is nothing like one that has been running at full employment for several years already.

Stay In Touch