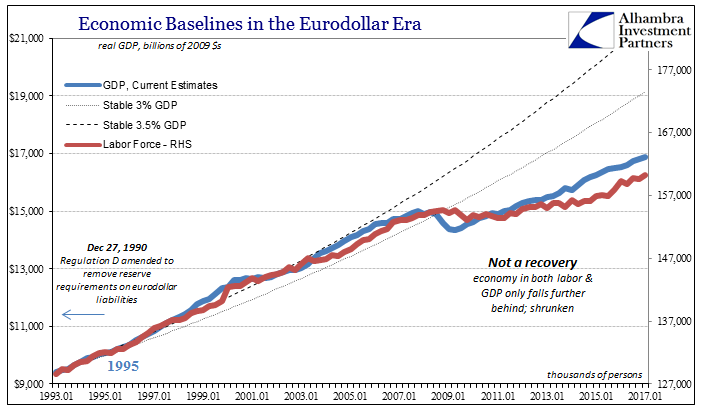

Real GDP in the US was revised up to 1.41% quarter-over-quarter (annual rate), still the fourth of the last six to be less than 1.5%. While economists and policymakers have taken to judging the economy by its downside, that is only because the extent of the global problem is revealed by complete absences of an upside. The occasional decent quarter doesn’t come close to making up for the more plentiful disappointing ones, let alone to still resolve the massive contraction in 2008 and 2009.

To reflect on this reality would be to underscore its historical uniqueness. Instead, policymakers and former officials, like Ben Bernanke, have taken their analysis in the other direction. Back in May on CNN, for example, the previous Federal Reserve Chairman called the economy “the little engine that could”, giving it a better than 50% chance of breaking the record for longest expansion in history.

He does so for very transparent reasons because this “recovery” has already broken records (postwar) for lowest expansion in history; so low, it doesn’t truly qualify as an expansion. The degree of plus signs is far, far more important than the number of consecutive quarters with them.

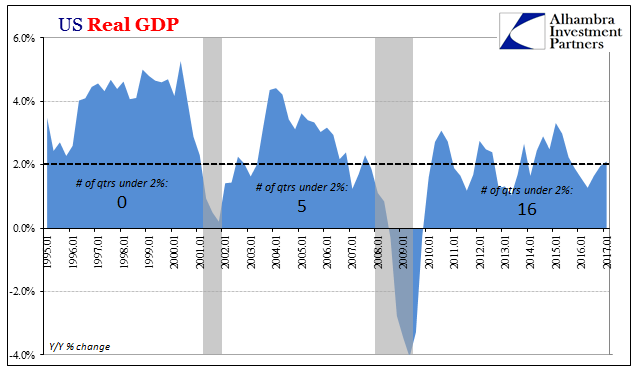

If we measure GDP year-over-year, in the late 1990’s there wasn’t a single non-recession quarter where GDP expansion was less than 2%. In the space between the dot-com recession and the Great “Recession”, there were five, and all of those were clustered at either end of the growth period, either out of the prior cyclical trough or heading into the next. During this nearly record expansion, sixteen, four full years’ worth, have suffered at what used to be considered stall speed.

It is a record of futility that we can only hope goes unmatched in our lifetimes – once “we” figure out how to get out of it, that is. The idea of stall speed used to be related to the business cycle, a low growth level from which the economy was in danger of falling into recession. Here we see its new definition, where the worst case isn’t recession but rather failing to ever achieve anything more than economic purgatory.

Record expansion is a linear idea unfit for these circumstances. Like the unemployment rate, it tells us nothing we can use to analyze either the current state or the likely future trajectory. That’s enormously important right now because there is and has been inordinate confusion about just what is going on.

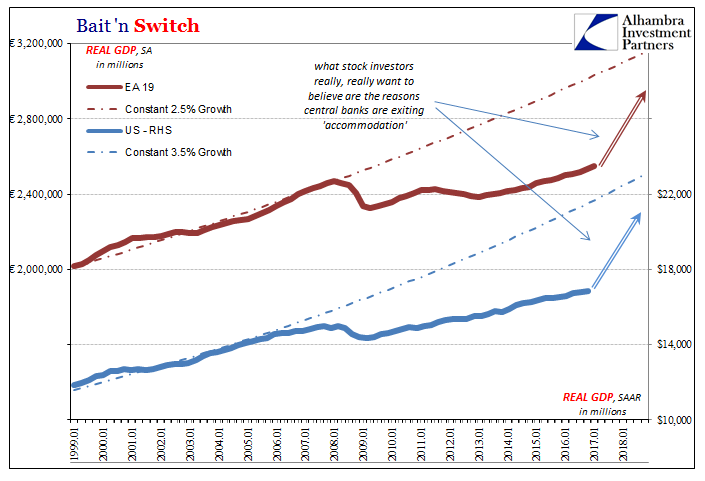

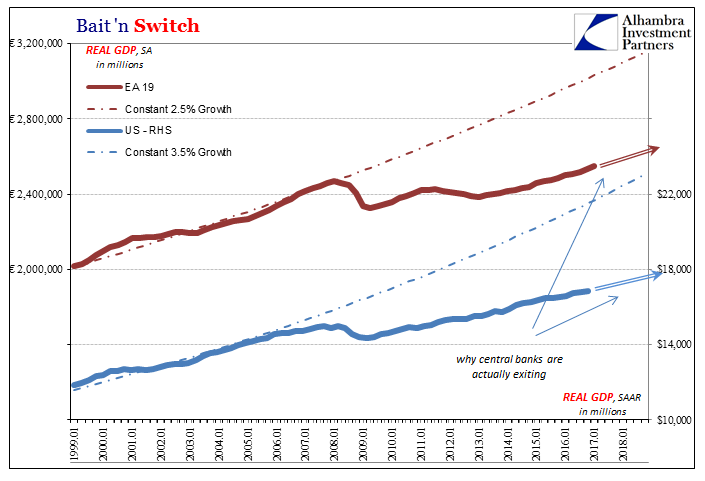

The Fed is “raising rates” while other central banks are suddenly “hawkish”, which many, especially participants in the stock market, are on their own equating with near-future economic acceleration. Yet, there is absolutely no basis for that expectation other than prior historical relationships. In the past, the Fed “raised rates” because there was at least some legitimate measure for growth; today, there is only the word expansion applied linearly to a non-linear problem.

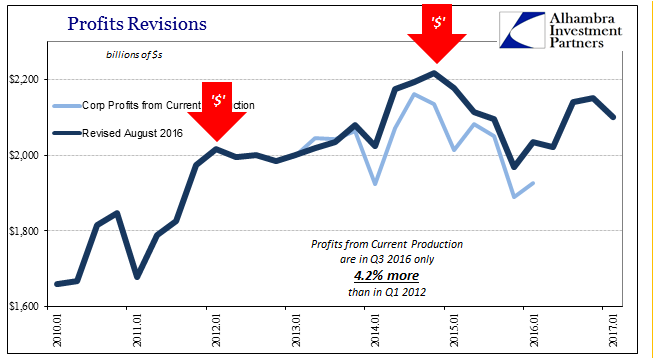

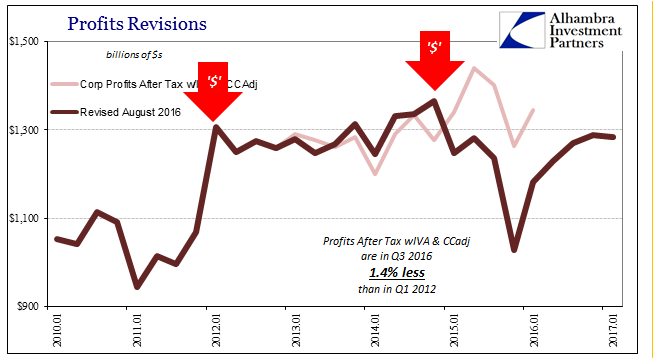

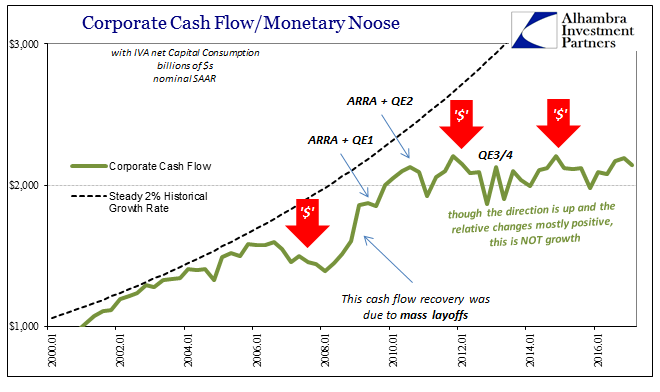

The more immediate manifestation in 2017 is the business climate. Companies aren’t making any more profits and generating additional cash flows. Without gains to the bottom lines of both income and cash flow statements (absent borrowing on the latter), the participation problem will remain and remain hidden by the inappropriate unemployment rate.

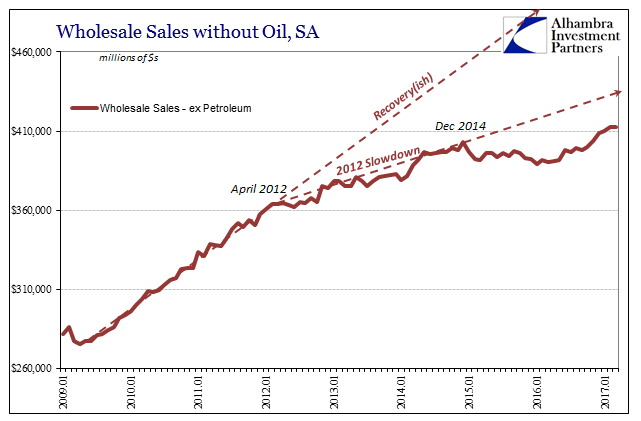

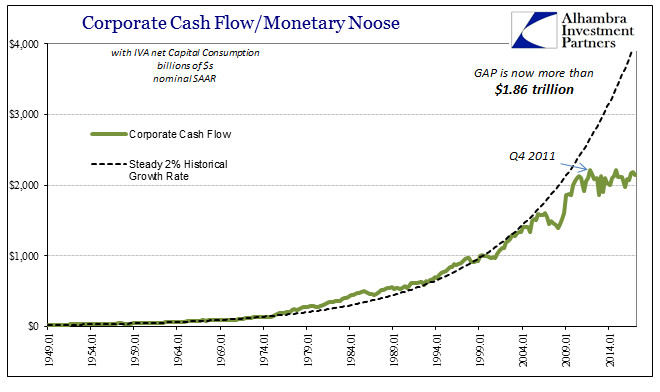

Revisions to Q1 2017 GDP included slight downward revisions to Corporate Profits from Current Production as well as Corporate Net Cash Flow. The bigger problem in those statistics as well as the rest in that category is that there has been no growth whatsoever in them going all the way back to 2012. It is not coincidence that the 2012 slowdown coincides with what was for Corporate America the end of any achievable recovery.

Orthodox treatment gives us only a binary option for framing analysis; either recession or expansion. What we find instead is neither, and worse. It is clearly not recession, though it does come in the form or repeated (2012, 2015-16) near-recession, and nowhere near the reasonable definition of expansion. And it is the time component that makes it the worst case. Claiming this economy is nearing the longest on record is a woeful account; add the word “reduction” instead of “expansion” and the description finally fits the true 2017 atmosphere.

What is missing here is opportunity.

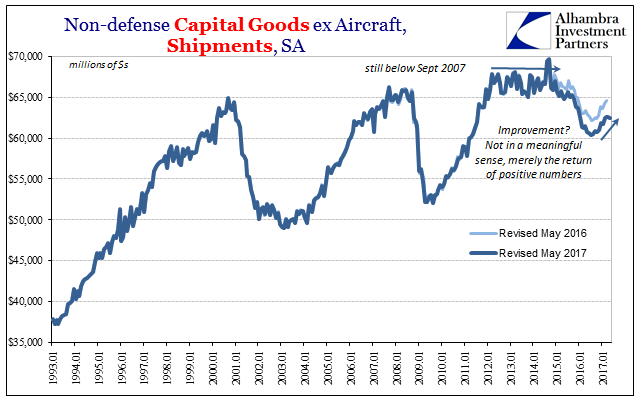

Another factor that may be contributing to a slowdown in longer-run output growth is a decline in the rate of investment. As is typical in a downturn, movements in investment were important to the cyclical swings in the economy during the Great Recession. And, as would be expected given the depth of the downturn, investment declines were especially large in this episode. However, in the United States, and in many other countries as well, the growth rate of the capital stock has yet to bounce back appreciably–despite historically low interest rates, access to borrowing for most firms, and ample profits and cash–causing concerns over the long-run prospects for the recovery of investment.

That was Federal Reserve Vice Chairman Stanley Fischer in 2014 trying to explain why economists’ predictions for expansion always produced instead apologies. In his formulation, the digression toward the end of the quote, he gets only two (mostly) correct by the data you see above: historically low rates and access to borrowing for most firms (arguable for smaller firms, but that’s for another day). The data presented above refutes the other two parts, profits and cash.

What do you do as a corporate business where profits aren’t growing and cash flow from operations is stuck languishing? Do you invest further in operations, where return on capital is so suppressed? You take whatever cash, including proceeds from debt, and instead invest where it will pay off the best, especially in a stock market (improperly) buoyed by belief in so much monetary “stimulus.” It is ultimately self-defeating if undertaken for long enough, which is what we observe in all the data above.

It gives new meaning again to near “record expansion.” Despite four QE’s and seven years of ZIRP, American (and global) businesses never foresaw opportunity so as to create the basis for recovery in productive investment. That was especially true by the crucial standards of liquidity preferences, the constant interruption of monetary crises that officials maintained even while they were happening were impossible. Janet Yellen just this week did it again. Better to just buy back shares than to trust Bernanke or Yellen to get the monetary equation right.

Stay In Touch