Almost exactly ten years later, central bankers believe they are so very close now to the end of the crisis. It doesn’t matter that they have made the same claim before, this time is different they say. Global growth is finally synchronized, and all the policy clocks can strike normal, or what passes for normal, almost all at once. There’s just this small matter of inflation.

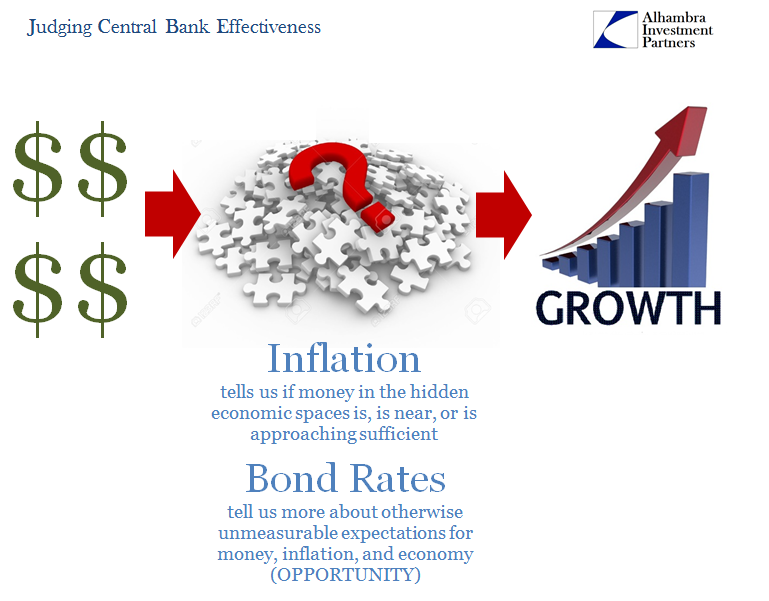

Except that it is not a small problem. It may be for you and me who welcome low levels of consumer price gains, or in the media hoping as always the most optimistic projections come true no matter how much or how convincing the evidence amassed against them (bonds). But for global central banks which have pumped trillions upon trillions into local economies, their officials can’t help but be asked “where is all that money?”

Inflation in the Group of 20 largest economies fell to its lowest level in almost eight years in June, deepening a puzzle confronting central banks as they contemplate removing post-crisis stimulus measures.

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development said Thursday that consumer prices across the G-20—the countries that account for most of the world’s economic activity—were 2% higher than a year earlier. The last time inflation was lower was in October 2009, when it stood at 1.7%, as the world started to emerge from the sharp economic downturn that followed the global financial crisis.

The contrast between then and now highlights the mystery facing central bankers in developed economies as they attempt to raise inflation to their targets, which they have persistently undershot in recent years.

The textbook definition of “tight” monetary conditions is sluggish growth and low to no inflation. If inflation is everywhere a monetary phenomenon, then its absence after so much policy effort is another conundrum. Or is it?

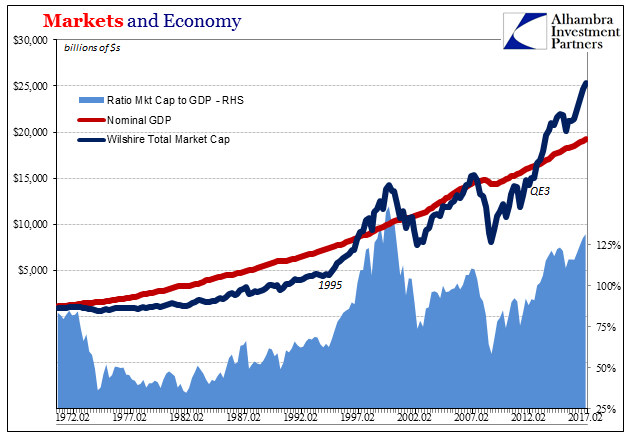

Some Fed critics have unhelpfully asserted that this missing money is in the stock or bond markets. They attribute to money what isn’t money, and hasn’t been since 1929 (I’ll get to this at a later time). Stock or bond investments are savings, and if stock prices are higher it isn’t because of QE but because what stock investors think QE might accomplish down the road (and always down the road, as valuations can attest).

In truth, the money isn’t missing because it was destroyed (and this counts in the same way the federal government declares slower growth a “cut” to whatever program). The Federal Reserve through QE increased the level of bank reserves, but those are only one line item of deposits among a broad menu (previously) available to bank balance sheets. It seems clear to me that most people who ponder the state of money in the world today have never bothered to closely examine a single one (and I include policymakers in that only slight hyperbole).

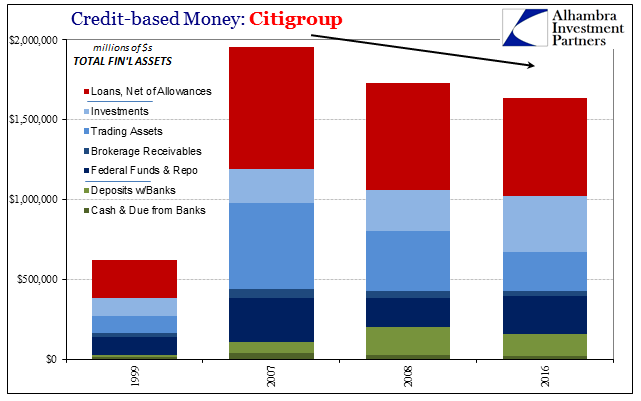

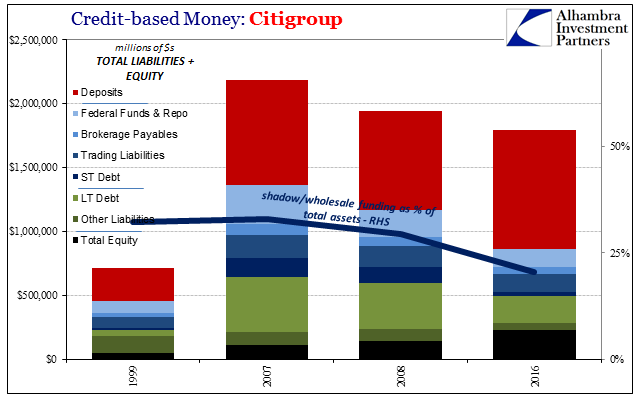

We can start with Citigroup, though any of the major global banks will work. In the eight years from the end of 1999 to the end of 2007, Citi’s balance sheet just about tripled in size. That was partially as a result of mergers, but mostly as monetary expansion in the modern sense. We needn’t go looking for the monetary genesis of the housing bubble, a true money-based asset bubble, for it is right here. That growth included a near constant proportion of wholesale and shadow liabilities, including by 2007 a net sourcing of repo and federal funds (borrowing more in them than lending out to others) as the bank’s total balance sheet swelled to more than $2 trillion.

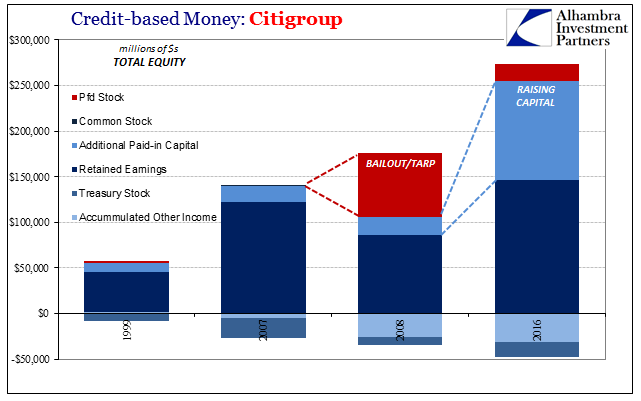

Since that time, however, Citi has undergone a more radical overhaul. The largest bailout in US history should do that to a firm, but it started even before the federal government got involved. Between the end of 2007 and the end of 2008, the level of federal funds and repo on the liability side (sources) had fallen by an enormous $100 billion. Trading liabilities and brokerage payables were cut by a combined $29 billion, while the bank retired and was unable to replace (on favorable terms, anyway) a net $65 billion in LT debt.

In fact, the only way the bank really survived was that bailout including TARP. The nearly $71 billion in preferred stock “investment” was the difference between what appeared to be sufficient capital and what would have been another likely Lehman situation (unlike Bear Stearns, there wouldn’t have been any way to force merge Citi with anyone else except the federal government via nationalization).

That deficiency was further rectified in the years since with almost $90 billion in additional paid-in capital. These are, of course, exactly the kinds of things we would want Citigroup to do after its recklessness (especially prop trading) in the pre-crisis period. If you wish to attribute that to regulations you are more than welcome, though in my view Citi so long as it was going to survive needed no more prodding than the markets in 2008 to become this way.

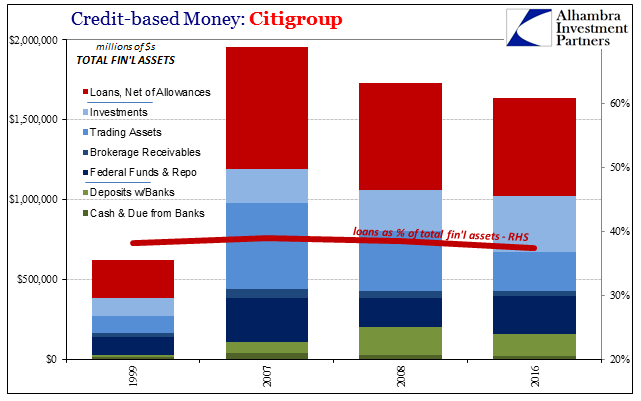

The issue is as always risk/return. Prior, it was widely believed there was little risk so volume exploded in every possible capacity including these shadow forms. But as Citi realized the error and more so the gravity of it, as it becomes more like a bank it has also become less of a wholesale bank. It’s only a problem (and a big one) because the global monetary system remains anchored to wholesale/shadow means. It is the two words that people searching for this missing money always overlook – credit-based, as in credit-based money.

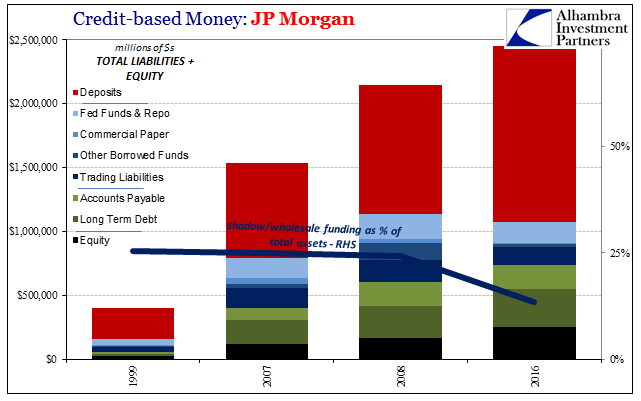

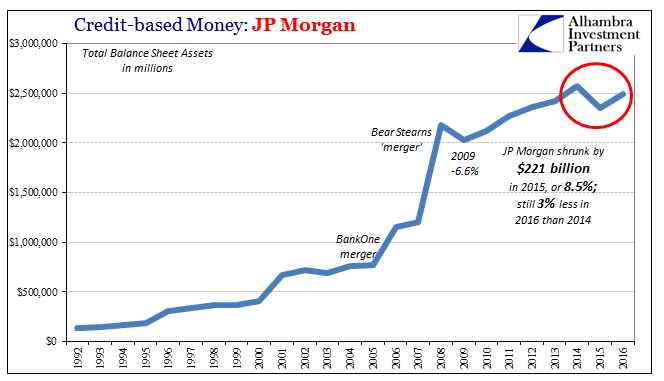

Again, the money isn’t missing it just disappeared as a result of the eurodollar system’s inherent contradictions related to risk. Even in banks that have nominally at least still grown after the crisis exhibit the same behavior as well as a much reduced appetite (dramatically slower and more uneven upward trajectory).

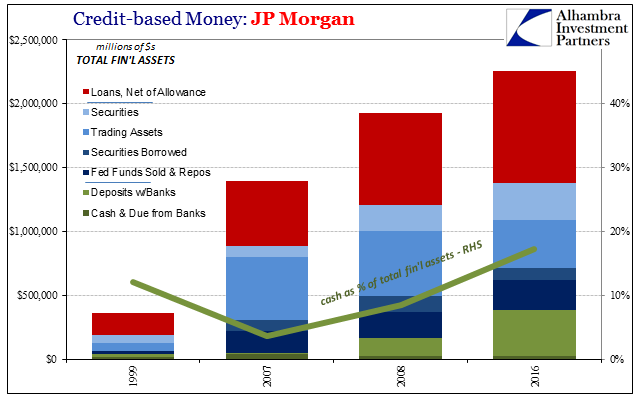

JP Morgan, for one, has obtained far more deposit liabilities (the byproducts of the QE’s) proportionally while holding a lot of them in excess cash (Deposits w/Banks, that bank being FRBNY) over and above pre-crisis levels. At the same time, its wholesale/shadow exposures have been significantly reduced (particularly its derivative books). And like Citi, it has increased its capital base, though mostly through retained earnings rather than stock floatation.

If you are being kind, you can claim that the QE’s added to liabilities (in deposits) as a monetary plus, but it was more than offset by the wholesale monetary minuses. That might propose simply doing more QE until hitting the “right” magical number where the addition of the former is greater than the subtraction of the latter, but Ben Bernanke already tried that.

The banking system merely stayed always ahead on the downside. More than that, however, the trend in assets is instructive here. As I examined yesterday, there is much more to the asset side than reliable liquidity (which QE bank reserves were never going to be as a static channel of liquidity). Balance sheet construction in all its dimensions was disturbed, permanently. It seems clear at least to me that even if the Fed had been able to figure the right quantity of reserves and make them somehow dynamic like wholesale methods, it still wouldn’t have been enough because these other parts are now absent or uncertain.

Liquidity is only one part of the equation, the mathematical result being smaller capacities.

The eurodollar was built instead on faster and bigger, and the global economy that it made requires all that, too. Smaller and safer while a commendable goal for banks just isn’t compatible with the eurodollar system that still remains. It is a drag on growth, and therefore inflation and cannot conform no matter how hard central bankers might try; and now just hope it all fixed itself as if nothing more than a product of enough time. But for two words, credit-based, they are missing what is otherwise right in front of them.

Stay In Touch