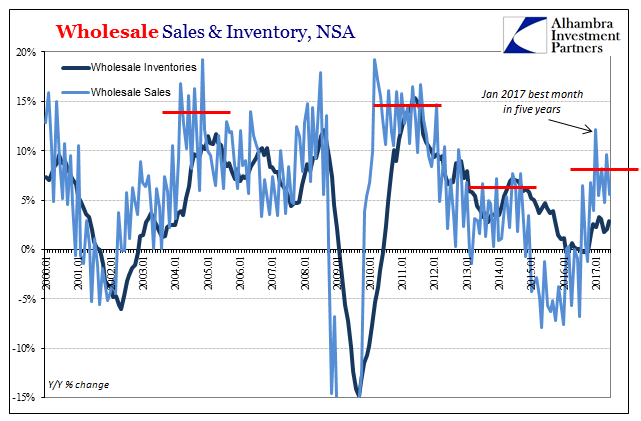

Last week the Commerce Department reported wholesale sales in June 2017 had risen by 5.6% year-over-year (unadjusted). Having increased by nearly 10% in May, and by the most in five years in January, 5.6% was instead the same kind of 2014 disappointment that is becoming far too common. These growth figures include petroleum sales on the wholesale level, meaning that like inflation rates oil price base effects have more to do with the outlier high estimates than any economic momentum.

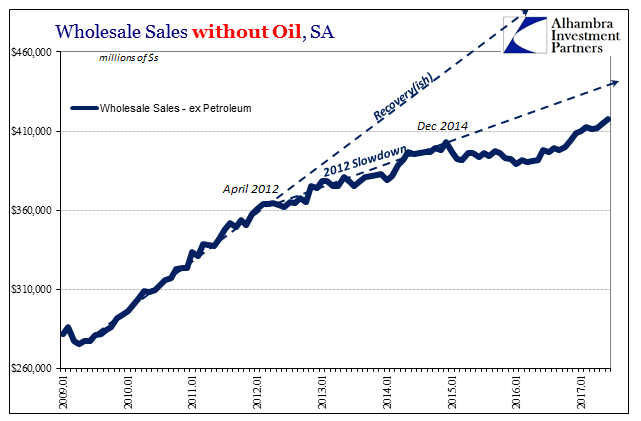

It is, in fact, the lack of sales momentum that is prominent. Inventories had never actually been drawn down by all that much despite recession-like contraction on the sales side. Even wholesale sales apart from oil were negative for some extended time.

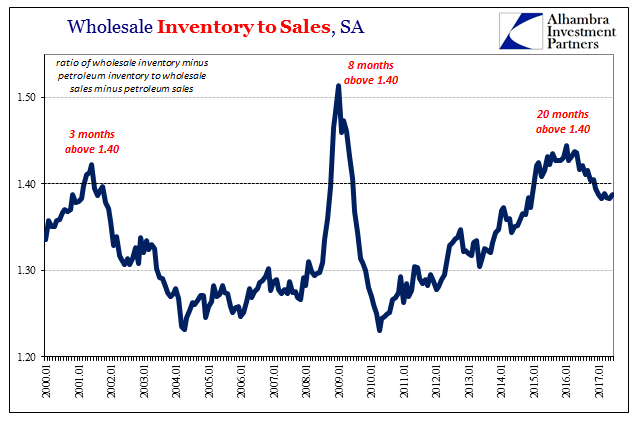

It may have been that businesses were expecting the mainstream narrative to come to fruition; that “transitory” factors would, given enough time, yield to the unemployment rate, or at least the economy it supposedly represents. Whatever the case, in 2017 inventories are rising again if only gradually at the moment.

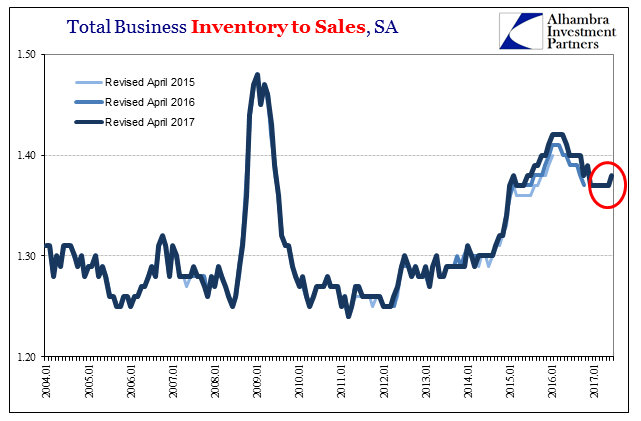

The combination of lackluster sales plus even slightly increasing inventory is the opposite of necessary rebalancing. Inventory levels compared to sales have stopped improving and in many cases are rising again.

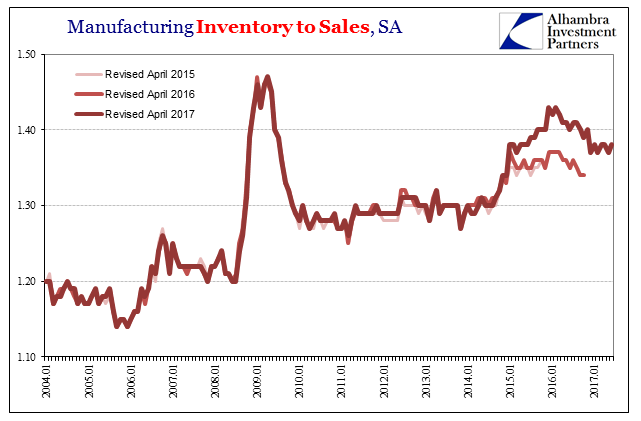

In the manufacturing segment, for example, the inventory-to-sales ratio jumped to a high of 1.42 during the near-recession in February 2016. That was up sharply from 1.30 at the outset of the “rising dollar” in August 2014, a level that had prevailed for nearly all of the “recovery” period 2011 to that time.

Despite positive sales again, the ratio improved only to 1.37 by January 2017, and remains stuck at that level (with it rising slightly to 1.38 in June). Thus, for the first time this year, the ratio of inventories to sales for Total Business increased. The behavior of that ratio has mirrored that for the manufacturing part of the supply chain. There was a rapid rise in 2015 into early 2016 and the downturn, but only a small improvement thereafter.

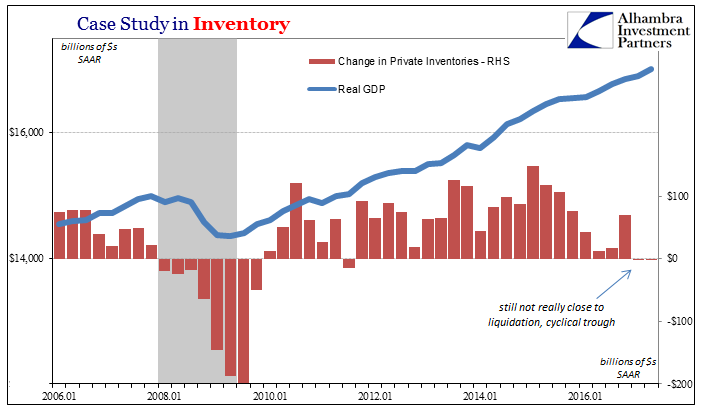

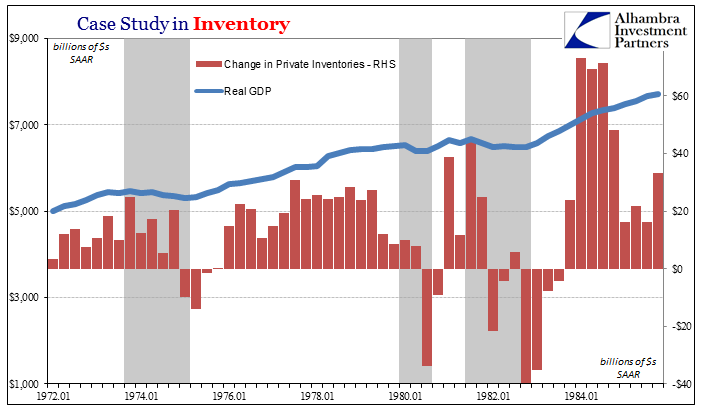

Even a brief historical investigation into business cycles proves that inventory plays a decisive role in their end. Every recession in the post-war period concludes with a dramatic inventory liquidation that brings about restocking and therefore the often intense and positive cyclical recovery forces.

The downturn related to the “rising dollar” may not be an official recession, but it was close. And while the current economy has operated for a full decade outside of the business cycle definitions and processes, that doesn’t mean cyclical processes are excluded or absent. The lack of economic momentum this year as an upturn is missing quite a lot, including robust restocking and the production gains that would accompany it.

So long as inventory remains elevated compared to sales, the economic risks will be/remain all to the downside. Even given the tremendous shift in sentiment from early 2016 to late 2016 that wasn’t enough by itself to trigger tangible and meaningful increases in production. What might happen, then, if sentiment shifts again back toward more pessimism? What might happen if that shifting sentiment is due to, or just accompanied by, greater liquidity constraints?

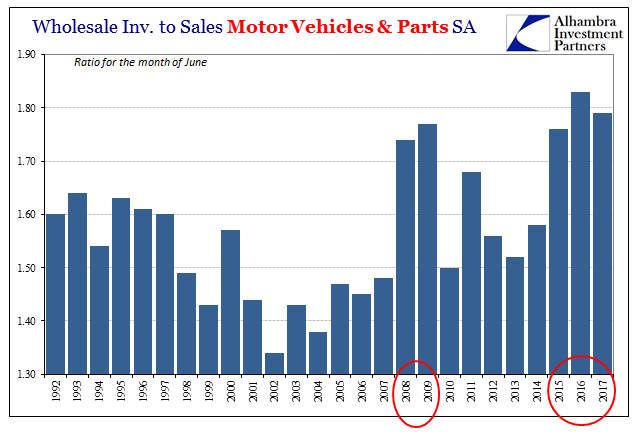

The auto sector has become the more extreme part of the imbalance, but by no means is it the only industry gripped by this paralysis. The Sword of Damocles still hovers, meaning that either robust growth must appear, just as it was expected in 2014, or inventory liquidation will take place in its stead. This was the constant state across all of the past three years, and yet here it still remains stuck between these extreme expectations.

This paralysis has to be attributable to the unemployment rate and mainstream commentary surrounding it. Firms are clearly reluctant to give up and undertake the necessary drastic steps befitting these actual circumstances. They are likely so because the unemployment rate suggests to them robust growth any time now.

But at the same time they are also bound to acknowledge reality. In other words, though “full employment” could apply to tomorrow it doesn’t apply to today, and surely didn’t yesterday. The tension between that economy and the one that “should be” coming (but increasingly appears as if it won’t) likely answers this inventory stasis, and a good part of the stagnant economy that continues without badly needed momentum.

Stay In Touch