In the US our economic data for a few months at least will be on shaky ground due to the lingering economic impacts of severe hurricanes. In China, the potential for irregularity is perhaps as great, though it has nothing to do with the weather. In a little over a week, Communist Party officials will gather for their 19th Party Congress.

The temptation may exist to deliver a somewhat better economic picture than has been the case. The government spent a whole lot in resources betting on if not straight economic growth by now than at least a plausible path to it. So far in 2017, China’s economy, as the global economy, has not come close to living up to expectations.

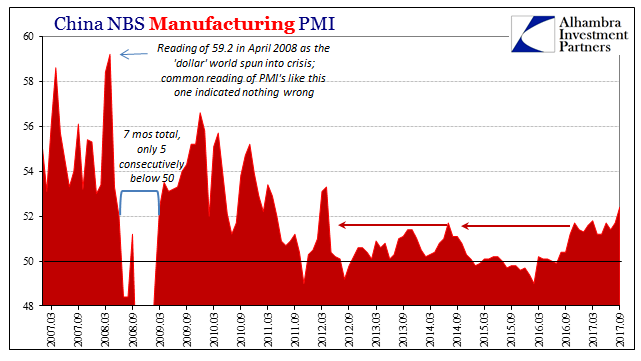

To that end, just before the Golden Week celebrations commenced to start October, China’s National Bureau of Statistics suggested that China’s core manufacturing sector speeded up to a what amounted to a 5-year high. The official PMI rose for September 2017 to 52.4. That was the first index value above 52 since two months above 53 in 2012.

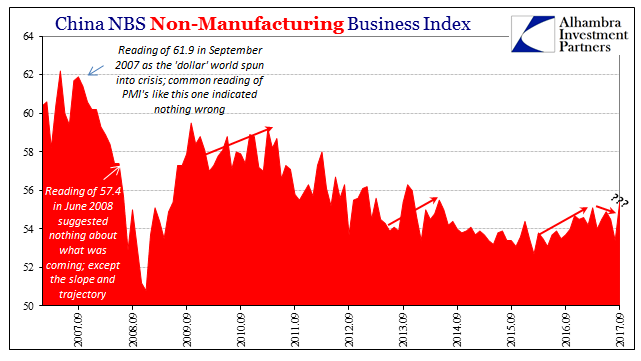

Not only that, the official non-manufacturing PMI also rose. After disappointing for five months, falling from 55.1 in March to 53.4 in August, this measure of mostly service sector activity jumped two full points to 55.4 in September. It was the highest level since May 2014.

The earlier trend in both PMI’s was far more consistent with other data in China as well as outside of it. There is clear but lethargic improvement in 2016 that at various points (depending upon the specific account in question) in 2017 either slowed remarkably or, as the non-manufacturing PMI, died off completely. It is a pattern we see replicated all over the world.

Given the possibility of political influence, it made sense to wait for corroboration before giving any interpretation of these results. It was very different for opening of the 18th Party Congress in November 2012, when China’s economy at that moment was believed to be capable of returning to pre-crisis growth. Though weakness was suggested as early as the “dollar” problems the previous summer, it was widely felt that any slowing would be temporary and easily overcome with the usual textbook “stimulus” (both monetary as well as fiscal).

While there were some concerns then, this time this is every reason to figure a paradigm shift. Pre-crisis growth is never coming back, at least not under the current global arrangement. Therefore, it makes some twisted sense to put as best a face on it as possible, particularly where General Secretary Xi Jinping’s reforms are still, we believe, a driving goal.

Going into the 19th with a “stable” economy perhaps appearing to be on the rise, best PMI’s in years, would be a vastly different construct than the one I think is more realistic as described by the familiar 2017 disappointment (and the risks those less positive circumstances immediately propose).

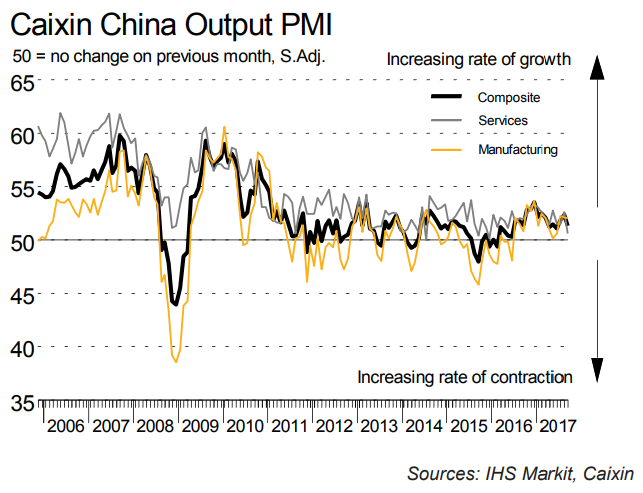

The possible corroboration of the official PMI’s would have come from Caixin. The private surveys for both manufacturing and the service sector had they shown even the same direction if not quite to the same degree would have lent credibility to the positive direction found in the official versions. But they didn’t.

Both PMI’s fell in September, the one for non-manufacturing dropping to a level not seen since December 2015. It was among the lowest/weakest readings in the whole series, and it doesn’t suggest anything good about China’s economic “rebalancing.”

The composite PMI compiled privately by IHS Markit and Caixin therefore resembles instead everything else in the global economy – growth and some improvement in the back half of 2016 and then a very disappointing 2017, perhaps increasingly so as indicated in far too many places.

These contradictions could, of course, be resolved favorably in the coming months. It may be that the official PMI’s are ahead of the private competing measures, and Caixin’s surveys will eventually show much better results in the months ahead.

While that is certainly possible, there is another divide to consider between them. The private PMI’s tend to capture more of the smaller and medium-sized firms, suggesting that the majority of China’s manufacturing and service sector is struggling to a greater degree than the larger firms more represented by the official calculations. That has been, after all, where most if not all “stimulus” has (or had) been directed, to the state-owned behemoths in fiscal spending as well as the credit resources to carry it out.

Data on a monthly basis is noisy by nature. I have to suspect that is truly the case for the official PMI’s for September.

Stay In Touch