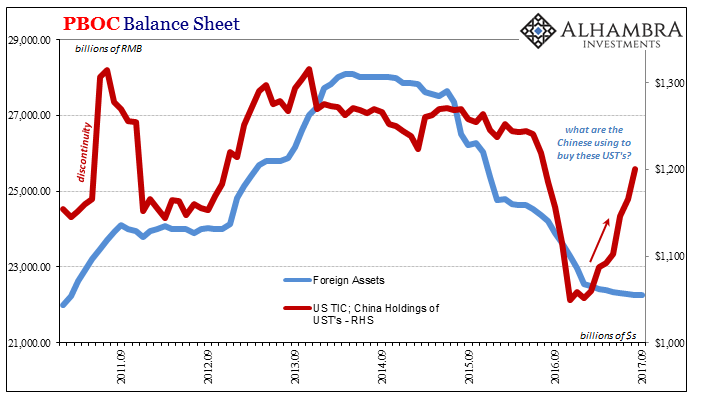

The Chinese have been on a UST buying spree of late, having announced to the world several months into it that they were intent on keeping it going. The idea in publicly endorsing and really highlighting their official activity was as a currency policy – to stabilize CNY against its highly disruptive tendency toward devaluation (which isn’t really devaluation).

How and where the Chinese are obtaining the “dollars” to accomplish this magic trick isn’t immediately clear. They are not, as they should be, coming from the PBOC’s balance sheet (on the asset side).

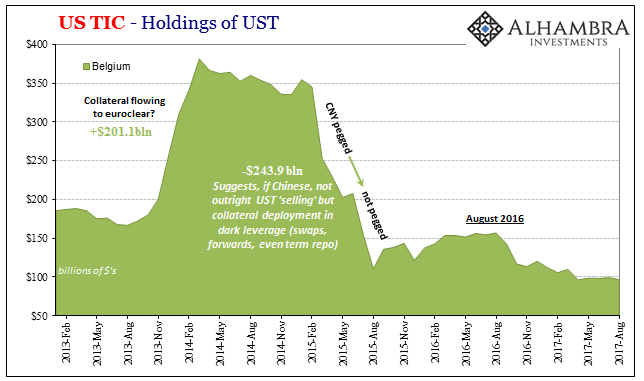

There are, actually, quite a few different ways to obtain US government paper – including borrowing the bonds, as well as via derivative transactions (swaps, forwards, term repos) that don’t show up on accounting statements in the manner they are actually structured (another problem related to footnote dollars).

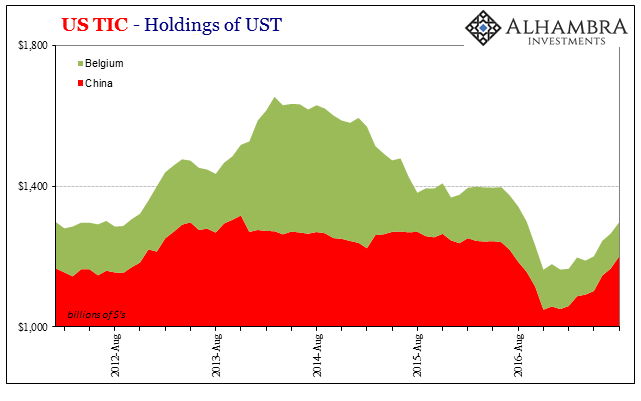

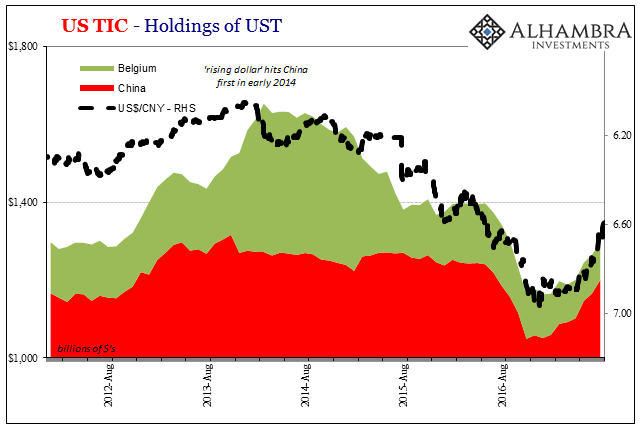

If we include Belgium with China, as we have every reason to suspect since 2013 the one tied directly to the other, the full-scale of the “rising dollar” becomes visible. The Chinese “sold” UST’s out of Belgium starting back in early 2014. The “rising dollar” hit EM’s first (in 2013) and then broadened out through China more heavily before it registered globally.

The sharpest decline in Belgian Chinese UST holdings occurred during those five months in 2015 when CNY was mysteriously and increasingly pegged to the dollar – until it catastrophically blew up in August 2015, proving again that even central banks incur massive costs for what they do. In other words, the Chinese were artificially supporting Chinese banks via “dollars” sourced likely in a heavy proportion of FX at Euroclear in Belgium.

Over the past year, the reduction in Belgian UST holdings has slowed and then stopped, that country reporting over the last five months a largely stable estimate. That might seem the happy ending to the story, a complete and total end to the “rising dollar” and its destructive Asian influences.

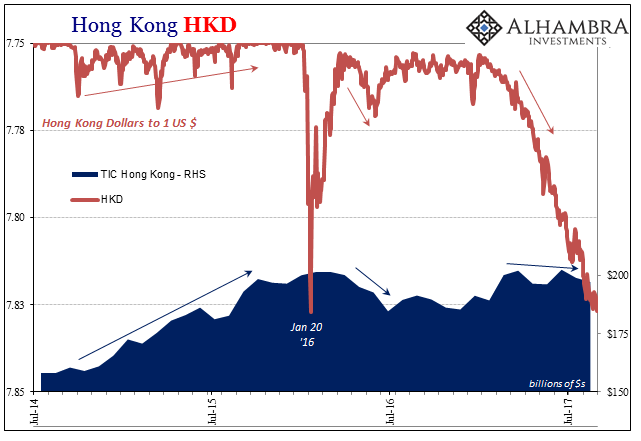

The problem is that China and Hong Kong are just as linked up if not more so than China and Belgium (which may seem strange no matter what). Hong Kong is its own system, with a separate currency as well as a very different monetary regime (currency board rather than central bank) for that currency. And yet:

Starting around September 2015, Hong Kong suddenly obtained a “dollar” problem (at least according to the TIC figures that back up HKD’s increasingly erratic behavior). The timing of it would have been very convenient for mainland China, especially in that big dip (in HK) through the middle of 2016.

Remembering that in non-linear terms lack of growth is contraction, it would actually seem somewhat proportional in the lack of growth in Hong Kong TIC (including outright contraction at several points) and the rise of a more complete monetary mess in HKD.

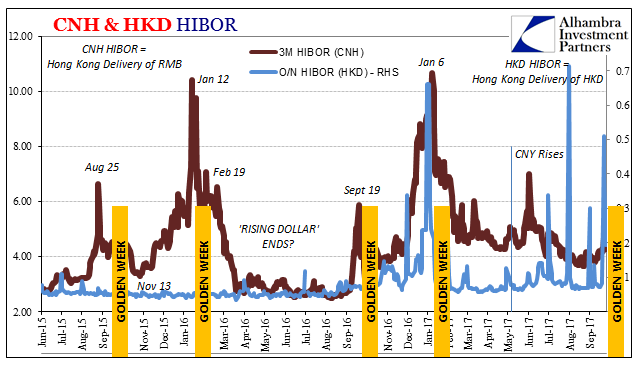

As tempting as it might be to draw the “dollar” line at China plus Belgium, it seems as if a broad survey of all China’s dollars must include Hong Kong within it. The TIC figures add more to what I wrote at the start of China’s Golden Week re: China & Hong Kong’s “location transformation”:

In other words, someone is very likely “supplying dollars” (borrowing them in repo?) through Hong Kong as one way to help alleviate China’s broader “dollar” problem. Since that by definition hurts RMB liquidity given China’s monetary pyramid, it really wasn’t surprising to see the PBOC announce an RRR cut for next year.

These would together cover to some degree China’s banks on both ends, “dollars” as well as RMB. What about HKD? It appears to be (part of) the cost of doing all this, one that Chinese authorities might be counting on Hong Kong’s sterling reputation to more easily absorb (at least relative to the shakiness of CNY’s). Those costs are not only one-time, however. Unless this works, they will be added to the bill coming due at the worst possible moment (in other words, just like all the previous attempts).

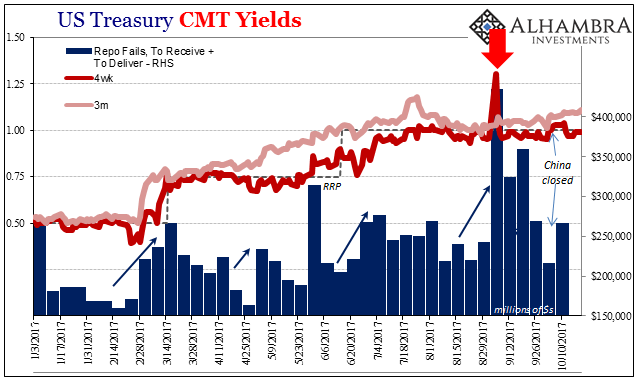

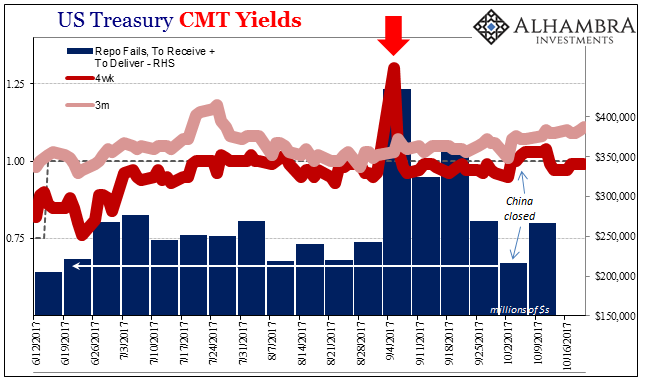

And there is one more piece of evidence to consider, provided separately by FRBNY and its tally of repo fails in UST collateral. China was closed the week of October 4, and Hong Kong (HKD) only partly so during that week. Repo fails that had surged in response to everything that changed the week of September 6, dropped to the lowest level in months without Chinese banks and China’s central bank doing business.

Once China re-opened for the week of October 11, repo fails rose back up to a similar level as the week before the holiday. T-bill rates moved in perfect sympathy with repo fails, the 4-week equivalent yield trading below 100 bps and the RRP “floor” until China was closed, rising above the floor during the Golden Week, and the dropping back below again the following week (as repo fails rebounded again).

It doesn’t suggest that Chinese “dollar” activities are the sole problem in US$ repo, but it does successfully test the marginal influence of those activities on that part of the eurodollar funding market. From there we can reasonably assume other methods and transactions in US$ funding pressures originating from that increasingly convoluted mix on the other side of the Pacific.

None of this is dispositive, nor should it be taken that way. It does add more depth to the “reflation” story and its possible end as redistribution matters a whole lot when the system may be rebounding but not really rebounding. In other words, from the Chinese perspective it may have made a lot of sense to try a covert CNY boost since they had done it (partially) via Hong Kong before. And since the eurodollar system was not really coming back much on its own, the only way to get CNY to do what it did was through hidden, artificial means.

With CNY showing lately a tendency toward devaluation again, and repo fails much higher than they might otherwise be, though the TIC data is several months behind it does perform a somewhat valuable service in helping piece together what may have been happening out in the global dollar shadows (footnotes). From there, we can (hopefully) at least attempt a better explanation of what may be happening now.

Stay In Touch