Back in September, the FOMC announced that it was in October going to start normalizing its balance sheet. The policy statement issued that day included all the usual qualifications of “solid”, “strengthen”, and “picked up.” The near-term risks to the economy, it was written, “appear roughly balanced.”

Not all was well with the economic situation, however, as the central bank’s policymaking body continues to wrestle with inflation. They might wish for political relief to their dual mandate, but in this case they have no choice but to live with the results – especially since they are largely of their own making. After mentioning economic risks, the statement then throws out there, “but the Committee is monitoring inflation developments closely.”

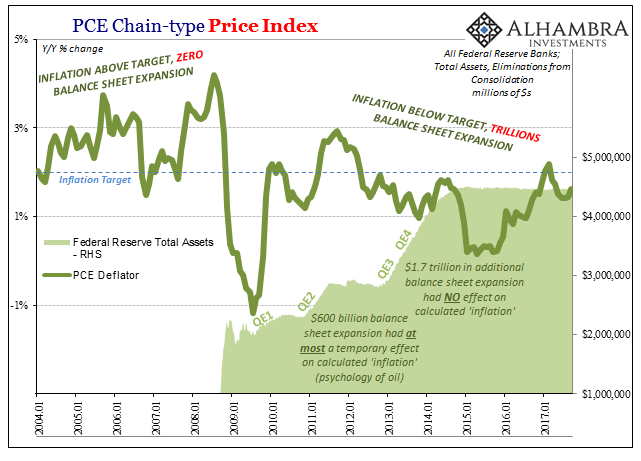

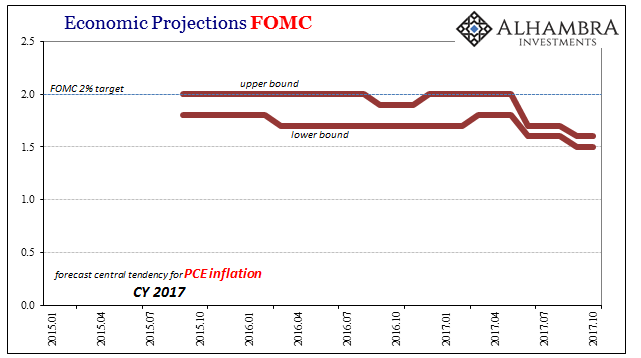

Having missed their definition of price stability, 2% sustained growth for the PCE Deflator, so many times, they can’t just ignore it, nor can they keep suggesting that it is delayed due to “transitory” factors.

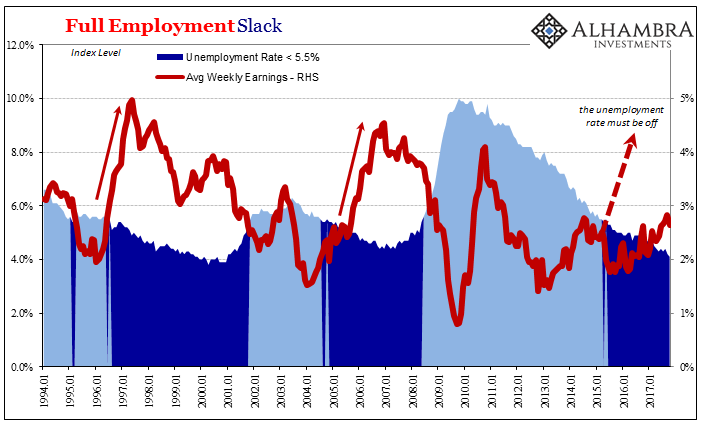

As noted this morning, the Committee has put most if not all of its inflation eggs in the unemployment rate basket. The one thing they are counting on that might otherwise clearly suggest inflation to behave is a low and lower unemployment rate. As labor market slack is used up and exhausted, employers will have to compete for workers, raising wages and pay, leading, the FOMC believes, to 2% sustained consumer inflation at some point.

That magical point, however, never seems to arrive, and worse the data never really suggests it is close.

No matter how low the unemployment rate goes, wage inflation remains clearly absent. There is a growing minority dissent within the FOMC because of this. Enough time has passed at a very low unemployment rate such that if it was going to happen it would have long before October 2017. Therefore, it is only logical to start to question whether or not policymakers know what they are talking about in this matter (and then every other).

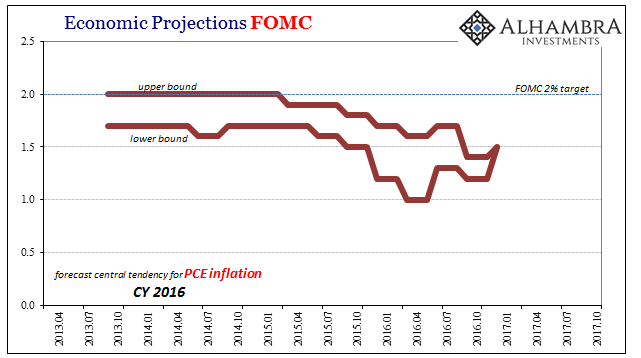

As it turns out, the Fed’s mathematical models, the real policymaking stuff at the central bank, aren’t so sure, either. You wouldn’t know it by the often confident rhetoric that members so often speak in public, but the math keeps turning toward doubt, too.

The statistical models before the “rising dollar” were uniformly sure in 2% inflation by 2016. They still are now, only the exact year at which this will happen keeps getting pushed further into the future. Up until mid-year this year, 2017 was supposed to be the one that found 2%; now it’s next year.

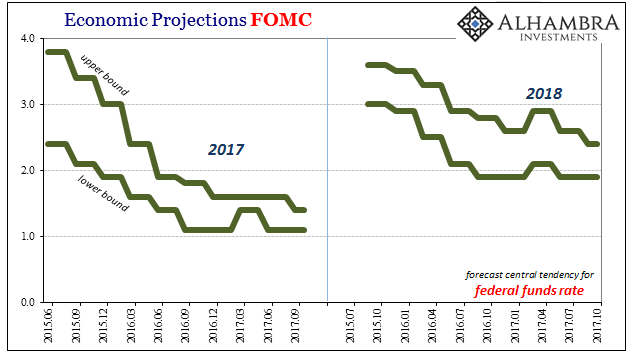

Because of this constant delay, the models keep reducing the trajectory for the expected federal funds rate.

In the middle of 2015, just before the full “rising dollar” really hit, the statistics were suggesting something almost like normal for this year – federal funds perhaps as high as 3.8%. Without any immediate signs of inflation risks, those projections have had to come down further at nearly every update. As of the September data run, the Fed’s regressions see only 1.9% to perhaps 2.4% federal funds next year.

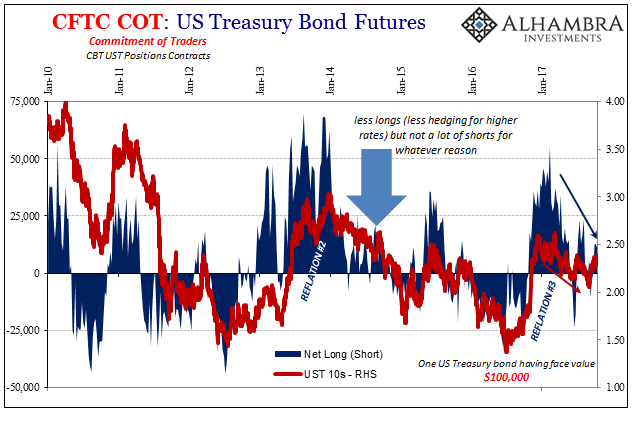

The projected path of inflation as well as money market rates (those that follow federal funds references, anyway) are two components of bond yields. While economists take a Fisherian, formulaic approach to interest rate decomposition, there is no reason to be so formal about it. In very general terms, we are told over and over that interest rates have nowhere to go but up and yet not even the Fed’s models, which are the very basis for nearly all the confidence about such things, are so sure.

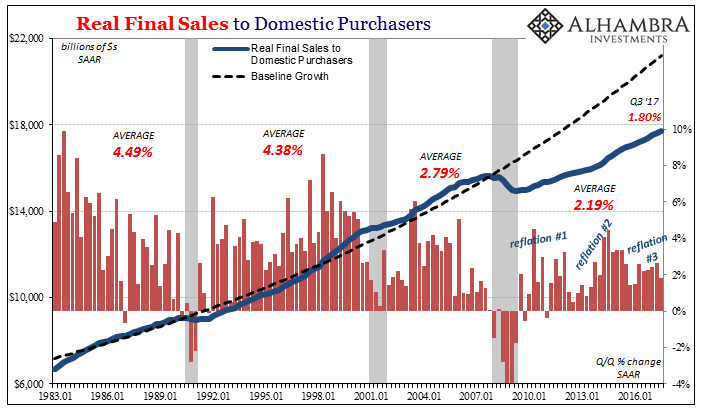

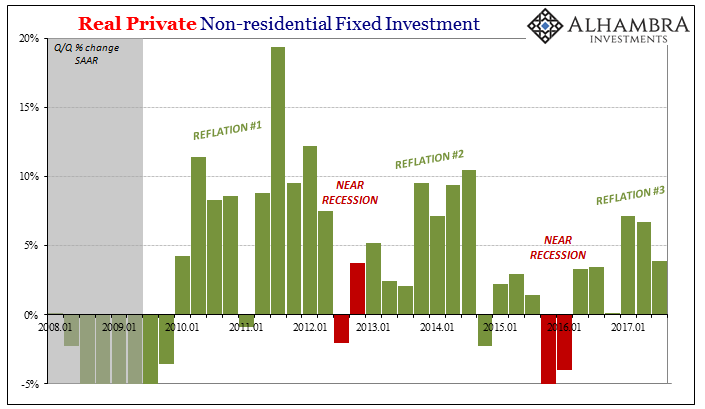

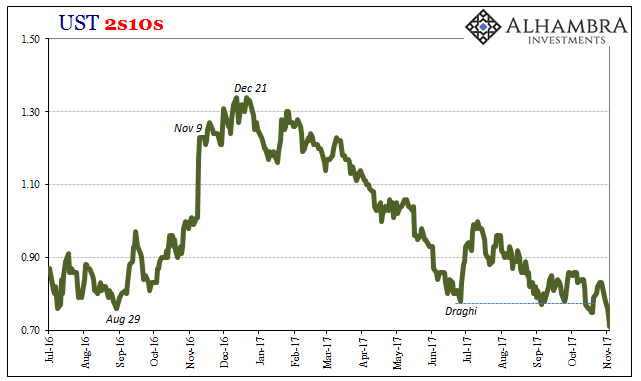

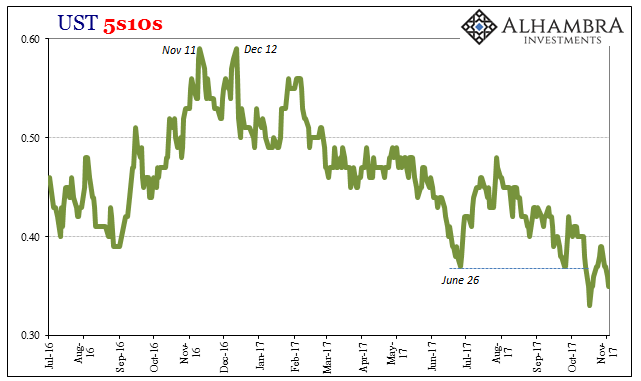

That’s a position that the market has taken a long time ago especially after Reflation #2 fizzled in 2014. In other words, the Fed’s math has taken several additional years to become more closely aligned with the Treasury market view about near and long-term economic risks. Official language aside, those cannot be “roughly balanced” else everything you see above would have been drawn much differently

And yet the myths persist (from Bloomberg):

Donald Trump’s choice to lead the Federal Reserve would take the helm after a year in which the central bank’s credibility has shot up in the bond market’s eyes. Under the guidance of Janet Yellen, policy makers have stayed true to their forecasts for gradual tightening in 2017, and traders are bracing for more of the same.

The idea that policymakers have any credibility is, as shown above, demonstrably false. It (likely intentionally) ignores the forecasts from years past because they are so laughably off base. The only thing that can be said true is that the Fed started this year thinking three to four “rate hikes” and so long as they do another one in December they remain consistent with that approach. So what?

It is nothing, nothing, like what was supposed to be happening now. The FOMC’s models just two years ago were mapping out some ten to sixteen “rate hikes” by now; that’s almost completely opposite getting five done, at most, in two years.

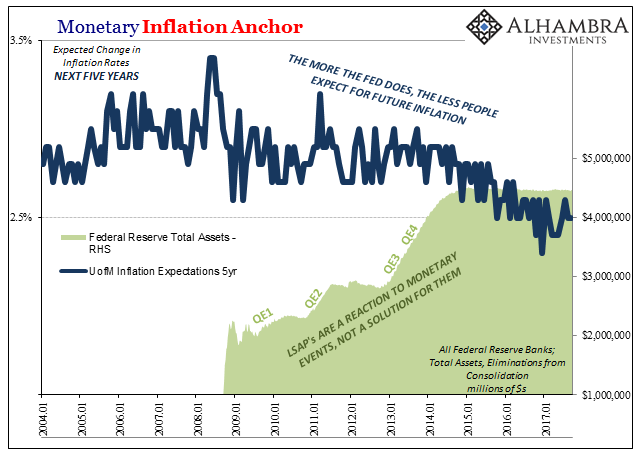

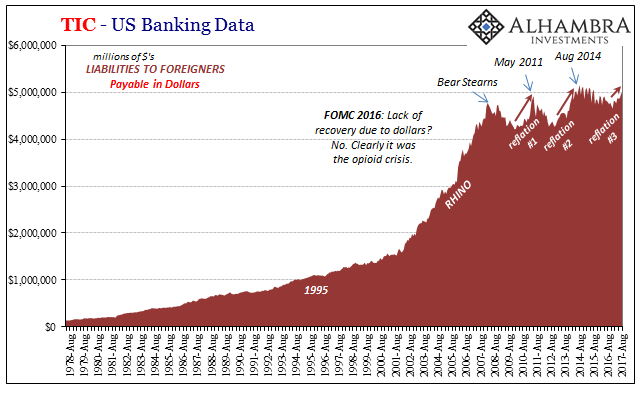

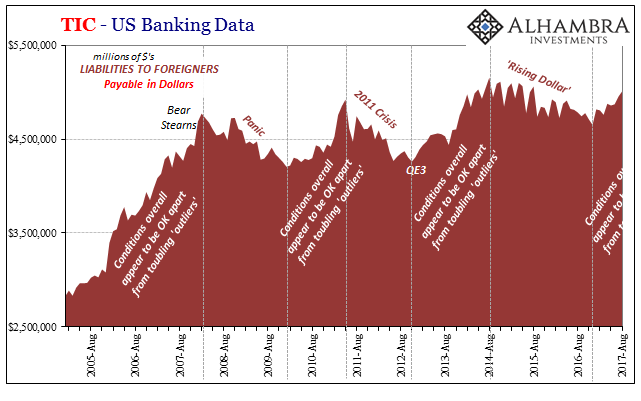

What really matters is why there is such a large difference, and inflation is playing the central role in that enormously consequential disparity. The Fed can’t figure out why inflation won’t behave, and since inflation is always a monetary phenomenon the bond market suspects the answer they haven’t allowed themselves to consider.

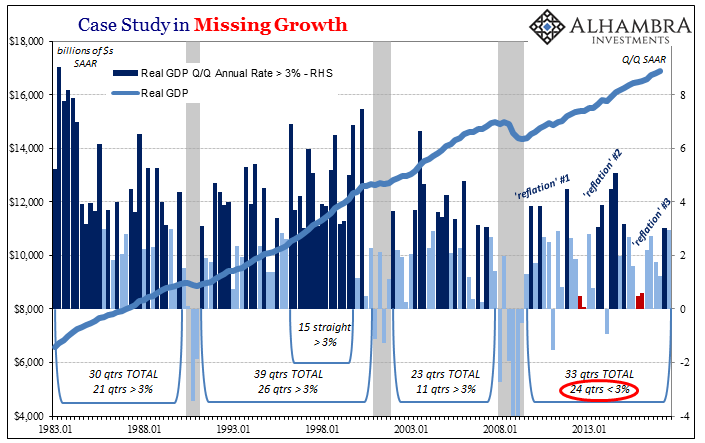

It was tight money (“dollars”) that shrunk the economy starting ten years, creating all that labor market slack, and it has been continued “tight” money that keeps economic growth to such a minimum (through uneven and shallow advances alternating with uneven and shallow downturns) slack cannot disappear sufficiently to drive wage inflation and then consumer inflation (assuming the economy actually works that way).

The interest rate fallacy is being reluctantly but relentlessly driven into even the econometric center of the US central bank. The yield curve collapses only that much more because the bond market is ahead of, not behind, the Fed.

Stay In Touch