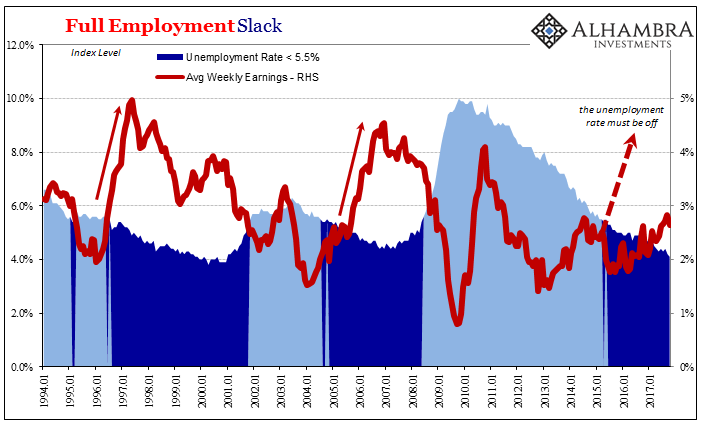

The whole thing really does unravel at the unemployment rate. If it indicates the correct view of the economy, even close to “full employment”, then what follows is fairly typical and orthodox stuff. In the context of what the Fed is doing, short-term rate hikes are leading the longer end of the yield curve toward a more hopeful future (though not necessarily one that is like full recovery).

If the unemployment rate is instead wrong, then: wages aren’t going to accelerate; inflation is in no danger of picking up because significant labor slack remains; meaning that the 15 or 16 (or more) million Americans left out of the official ratio do matter; and therefore after ten years the US and global economy still has much bigger problems than the ridiculous dots. For the Fed, it would be huge, failing on both of its statutory mandates in a very big way.

Given these stakes, it’s no wonder the word “transitory” has been used as much as it has. Janet Yellen has to be right about this one, or it all falls apart. That’s why more and more there are publicly voiced dissents, the latest from influential San Francisco Fed President John Williams who now questions some very basic policy assumptions (though not nearly basic enough for actual answers).

Vice President Stanley Fischer abruptly retired last month, cryptically citing only “personal reasons” for his departure. Perhaps he was upset his name wasn’t forwarded into final consideration for the Fed Chairmanship, or that Yellen maybe wasn’t being taken seriously enough; or perhaps Fischer doesn’t like where the evidence is really taking the Fed, the now non-trivial risk that there could eventually be blowback due to present policymakers’ unraveling worldview.

Fischer has been joined just recently at the exit door by FRBNY President Bill Dudley. Though he moves up his retirement by only six months, it places the Fed in an unusual position of very public churn.

The president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York is set to announce he will retire next year, about six months earlier than scheduled, adding to an unusual wave of turnover among the central bank’s top monetary and regulatory decision makers and ushering in new uncertainty about its policy course.

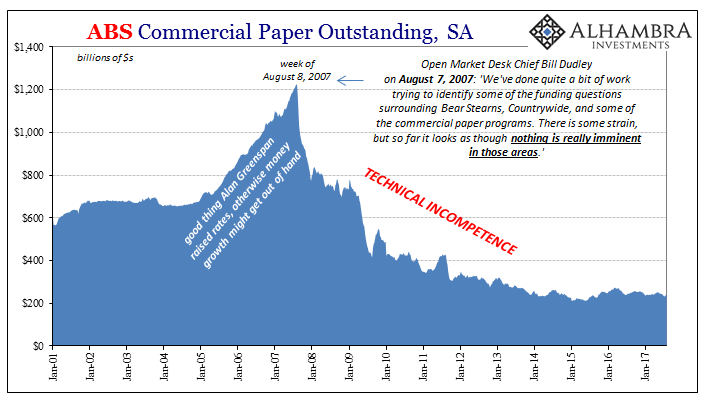

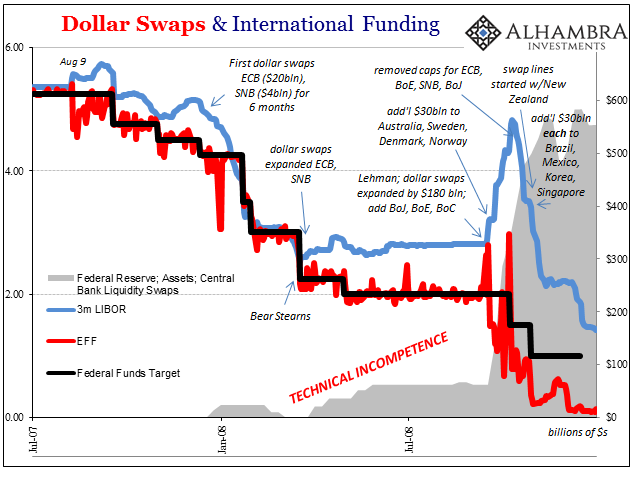

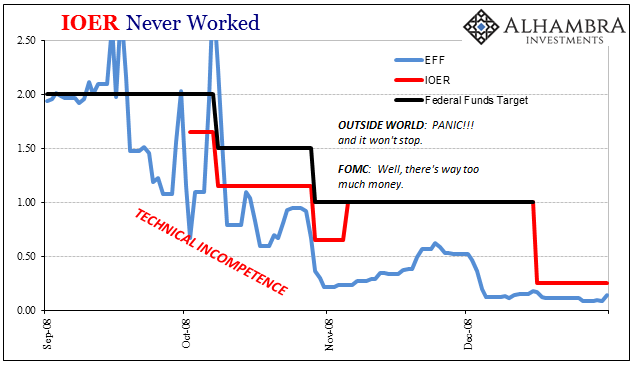

People are increasingly uncertain about the Fed’s course because the Fed is increasingly uncertain that it knows what it is doing. Bill Dudley, as I have recounted more times than should ever have been necessary for a man of his position, is front and center in those crosshairs. The words technical incompetence fall on his resume more than anyone else’s apart from Ben Bernanke and Janet Yellen.

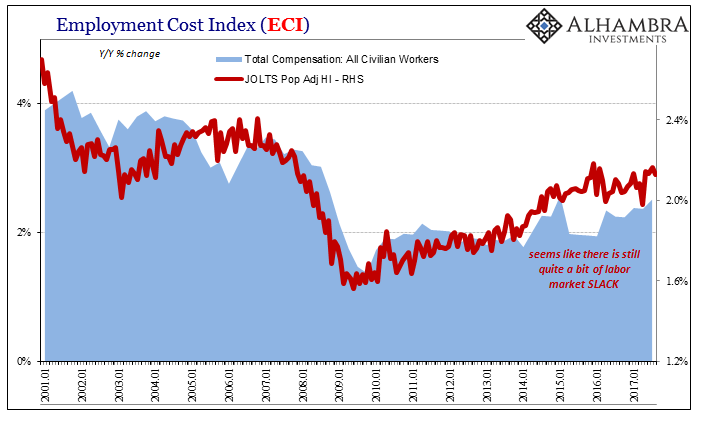

Incoming data on the labor market, wages, and inflation are all still non-conforming. It can’t be this way this far into 2017 and lead to anything other than great questions about what is going on, and what the US central bank actually knows about the economy in a real sense outside of statistical models that fail time and again.

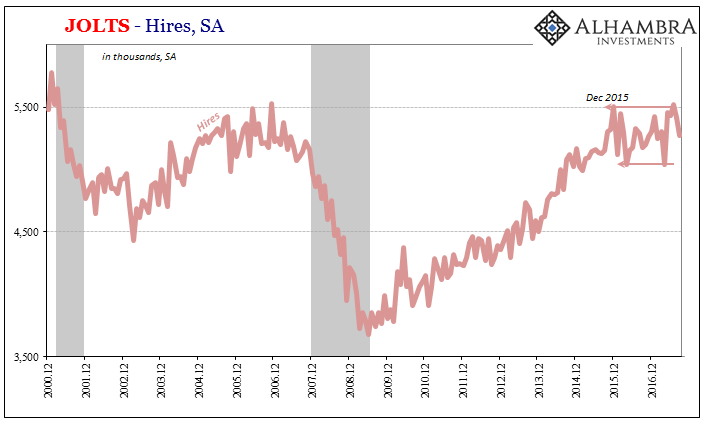

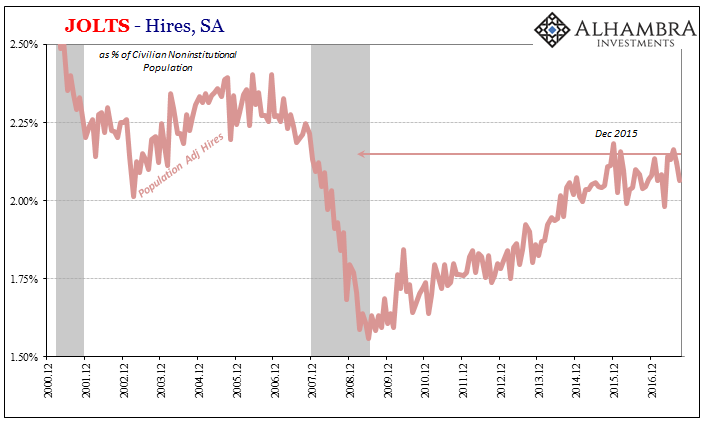

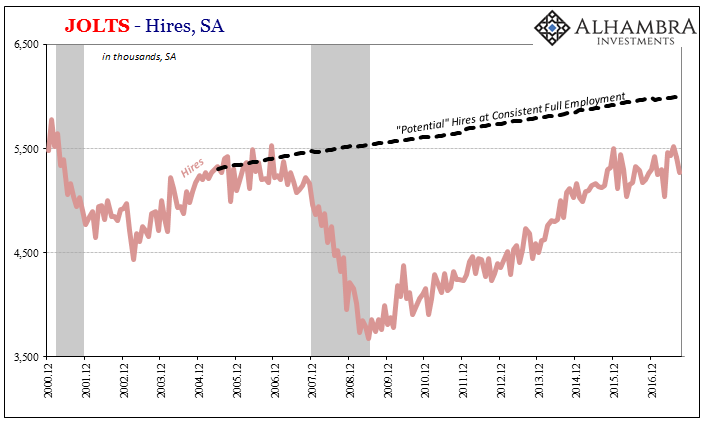

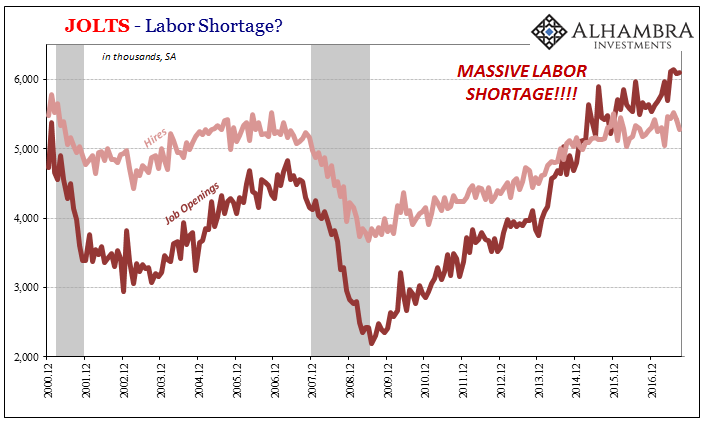

The BLS estimates in its latest JOLTS report that the rate of hiring activity in September 2017 (a level certainly impacted by hurricanes) declined to 5.27 million. Rather than focus on that specific monthly number, the estimate remains well inside a range established back at the end of 2015.

That view is consistent with the more widely followed Establishment Survey payroll reports, which have shown a slowing rather than an accelerating labor market that would be more in line with the unemployment rate.

More than that, adjusting the Hires level by population growth gives a sense of possible remaining labor market “slack.” The current level is about equal to the peak period in the last “cycle” from 2005-06, but in between the pool of potential labor has expanded by about 26 million since then.

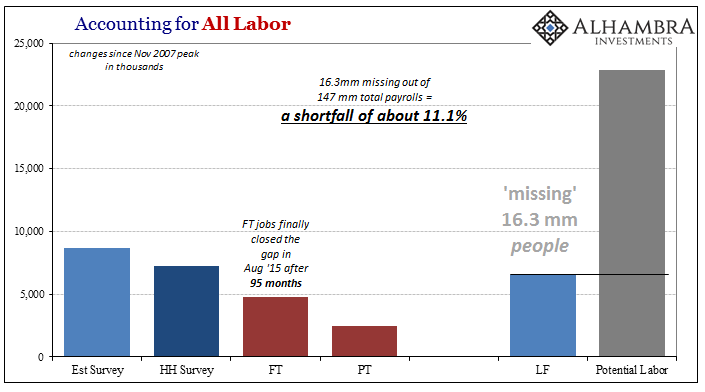

This alternate calculation suggests that the US economy at a consistent full employment would have experienced about 6 million Hires in September rather than 5.37 million. Interestingly enough, that’s about a 12.2% shortfall, which is pretty close to the same one (in percentage terms) we calculate for our estimate of how many Americans are potentially missing from the denominator of the unemployment rate.

Together, these tell us of an economy that shrunk and never came back.

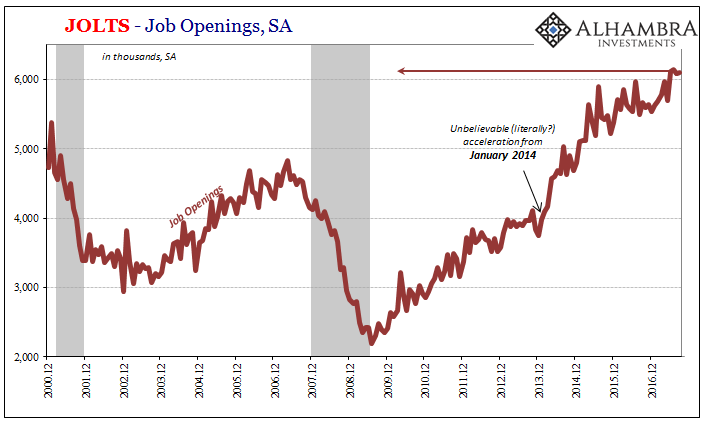

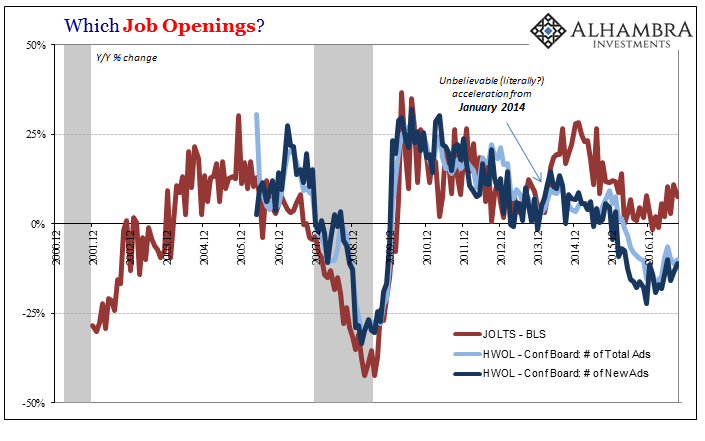

On the other side of the JOLTS data is Job Openings, which projects a completely different view of the labor market. Like the unemployment rate, it suggests that the US economy has to be running up against a labor shortage, maybe even a dramatic one.

But there is, as noted before, conflicting views on this element of demand for labor. The Conference Board’s index of Help Wanted On-Line (HWOL) ads, for example, is nowhere near what the BLS version of what is supposed to be the same thing is displaying.

More than that, however, there is just no indication that the labor market is tight or even tightening to the point of significance. The remaining slack still indicated by population-adjusted HI as well as the full account of missing labor is consistent with what we find all throughout the wage and broader compensation data. The unemployment rate, as Job Openings, has been at an extreme for two years which is plenty of time for wage pressures to have long ago manifested.

It has been, in fact, too much time such that it now more and more discredits its view of slack, wages, inflation, and therefore what has been going on in the economy going back to the beginning. If I were a Fed official sticking to the “transitory” explanation for this long, I would be very uncomfortable, too.

Unless all of this changes real soon (a likelihood that decreases every additional month further from when it should have back in 2015), those 16.3 million missing have to be accepted as part of the ongoing problem. And in incorporating them (correctly) that means everything in the policy response going back to 2007 has to be thrown out and rethought. It would indicate Bernanke wasn’t courageous at all, instead thoroughly incompetent.

An influx of new FOMC members might reach similar conclusions, or at least for the first time be open to considering them, though not just about Bernanke and/or Yellen’s tenures but also those of any remaining members who failed to register anything but the official stance/view. At FOUR POINT ONE, how much margin for error is left before some very uncomfortable questions lead toward blame? The economy right now remains on its small(er) upturn, making this a less urgent task, but what happens if (when) the next downturn comes along?

Stay In Touch