Ever since Robert Solow and Paul Samuelson wrote of an exploitable Phillips Curve in 1960, economists have had dreams of being able to precisely control the economy through the exchange of inflation and unemployment. The original paper, the one sold to, and bought by, the Kennedy Administration, theorized it was possible to sort of “purchase” very low unemployment by allowing slightly higher inflation. It was a disaster.

The Phillips Curve and really this kind of demand side economics lost favor in the 1970’s for the obvious reasons of the Great Inflation. But it never really died out. Even today, the Phillips Curve remains an integral part of monetary policy and orthodox Economics. It doesn’t lead policymakers toward an active management approach like it once did, but it does inform them, they believe, for when they might need to act in a certain way.

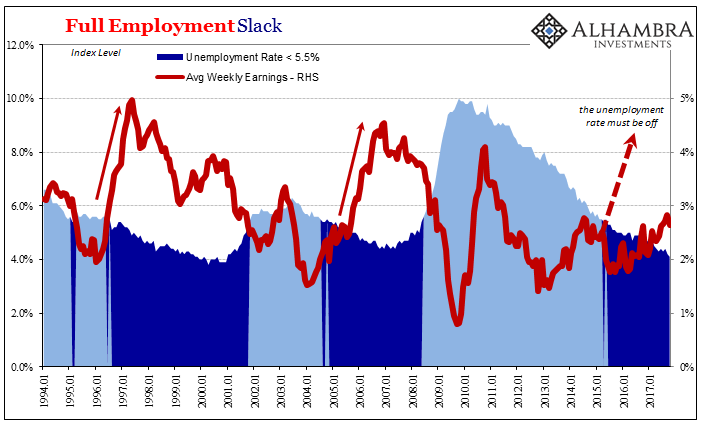

The meat of the issue is the idea of cost-push inflation, that when unemployment falls low enough so as to reduce or even eliminate labor market slack the resulting increased competition for increasingly scarce workers will lead to rising wages; basic economics of supply and demand. Those wages gains will be passed on to consumers as higher prices, which those consumers can afford being paid more per unit of labor output.

For central bankers then, the point at which that starts to happen is their signal for normalization on either side. Wages that start to accelerate after a cyclical trough tell policymakers their job is done, and done well (actual full employment). You can see why they might be keen on finding the smallest signs of wage pressures.

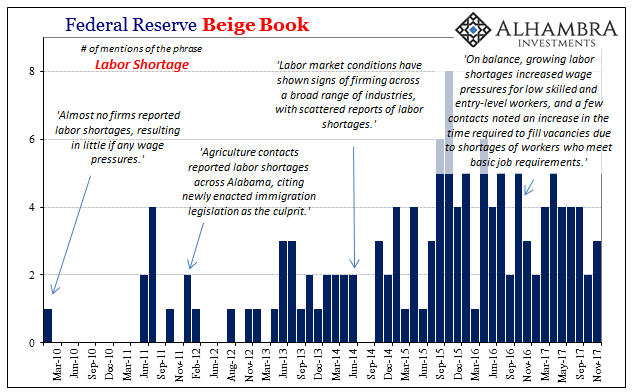

Because that kind of healthy action has remained almost completely absent in the labor market statistics this time, especially as the unemployment rate has fallen to now extremely low levels, monetary officials have had to use anecdotal evidence to suggest that this is all happening anyway in at least the initial stages. It has typically taken the form of stories about “labor shortages” that if they were real would lead to the kinds of wage gains and thus successful monetary policy execution they are all desperately seeking.

In short, if the labor shortages reported are emblematic of the whole then there is every reason to suspect that though wages and incomes aren’t now accelerating they will at some point in the near future. In strict policy terms, that means act now before things really get out of hand even though the data dependent FOMC doesn’t have that particular data in hand right now.

While that is possible, so is the other side; rather than being representative of the full labor market, policymakers have cherry picked certain stories and isolated cases to suit their certain, and obvious, bias.

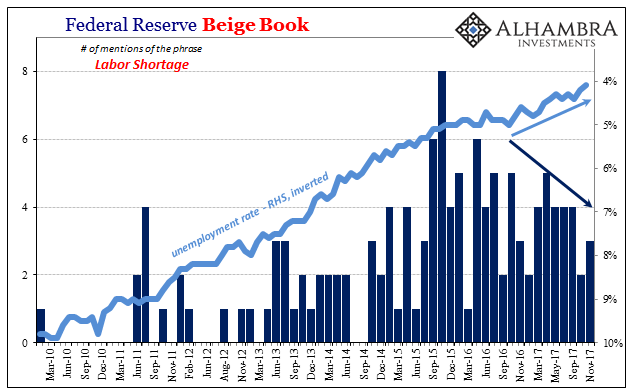

Ground Zero for this conflict is surely the Federal Reserve’s Beige Book. The whole point of the compendium is for anecdotes about the economy drawn from local contacts across the whole country. That made sense for earlier times when statistics were infrequent and not so encompassing. Today it’s an exercise in fantasy, but an important one nonetheless in this important inflation context.

The Beige Book does not tell us what the economy is doing; it instead indicates what the Fed thinks the economy is doing.

Fed officials today still refer to the Beige Book quite often in their discussions, though from a truly objective point of view it isn’t at all clear why they should. It is notorious for getting things wrong, and often very wrong. Perhaps that is because any anecdotal report filtered through the bureaucratic apparatus in any official setting will become by nature an echo chamber. The various Fed presidents will do what is perfectly corrosive, which means they will select stories or conversations they have had that best reflect their own beliefs and biases. If the Fed presidents are all wrong, as they have been, the Beige Book will necessarily follow, not lead.

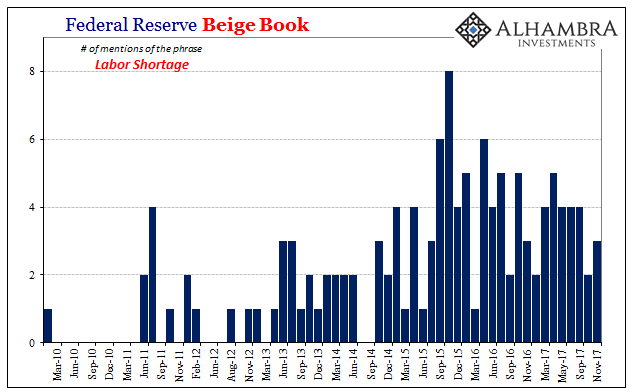

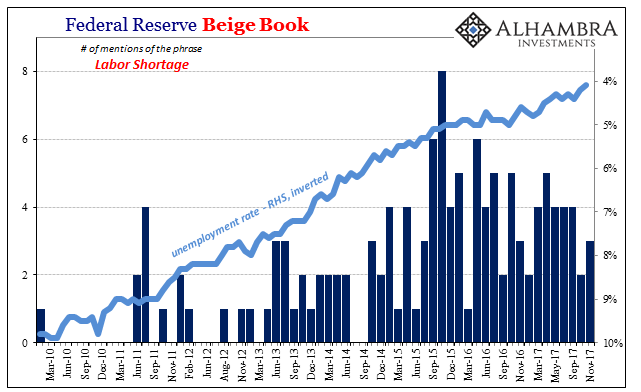

The labor market case proves that to be true. The phrase “labor shortage” was first mentioned all the way back in January 2010, not because it was happening somewhere but because at that awful time it wasn’t evident anywhere. The incidences of using the words in each Beige Book have clearly followed a pattern which on the surface seems quite consistent with the track of the unemployment rate.

As it has gone lower, the frequency with which the phrase has been deployed has increased. That’s also true of the context in which it appears, starting with early 2010 referencing no “labor shortage” to later Beige Book editions that deploy clearly escalating rhetoric in using it.

But is that really tied to the unemployment rate?

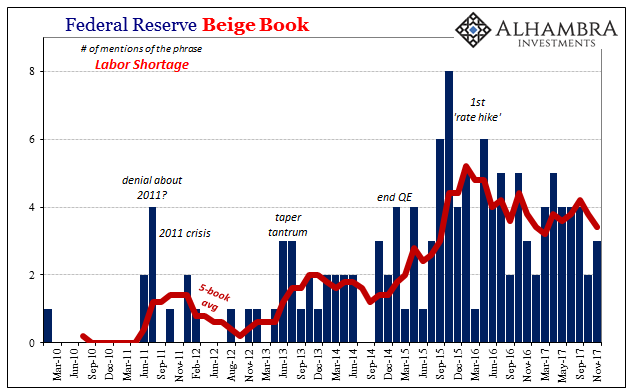

If we instead calibrate the “labor shortage” use in each Beige Book by key monetary policy events, another very different possibility unfolds. It seems far more likely that references to a possible shortage are a product of pressure rather than thoughtful, considered analysis derived from useful information. The frequency rises perhaps to justify the actions eventually taken by the FOMC as its members attempt to convince themselves and each other these actions are proper given the lack of broad data confirmation (not data dependent, present tense, but projected future data dependent).

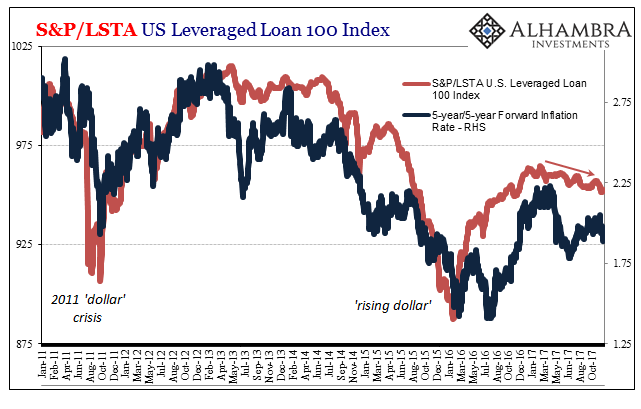

I doubt very much it is coincidence that the term “labor shortage” was used most heavily in September and October 2015 – the very months that most outside observers were convinced the Fed would have had to begin its “exit” by “raising rates.” It was also those same months where “global turmoil” of the “rising dollar” began to strike heavily at the US and global economy, setting them up for what really was an embarrassing opening move.

The Fed finally did act in December 2015, not because the economy was improving (it was doing the opposite) or because wages were accelerating. What this anecdotal study of anecdotes really suggests is that the policymaking body talked itself into acting because they still want to believe the unemployment rate version of the economy, the one where the Phillips Curve continues to be a valid theoretical foundation for monetary policy.

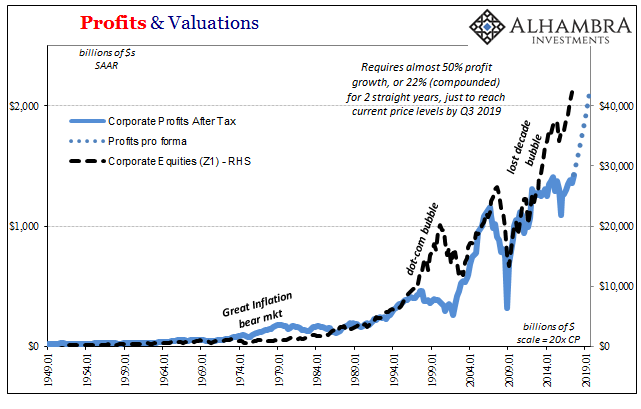

Again, we know why they want to think this way, because if it turns out to be the correct view at some always unknown future date they are totally off the hook – it would mean it really was opioids, a low R*, or something that monetary policy just could never address.

What may be even more important now is the trend after that first “rate hike.” If you believed labor shortages were becoming more frequent in the middle of 2015 with an unemployment rate ready to dip below 5%, what must you believe in the middle of 2017 with it getting set for less than 4%? Anecdotally, that would suggest the labor market is on fire, with wages pulling something more like a 1970’s Great Inflation cost-push extravaganza.

Yet, of course, the statistics instead show that is nowhere near the case. If you are sure about what the labor market is doing in 2015 based in some good part on Beige Book stories but two years later it still hasn’t shown up in the numbers, it would make sense to go from LABOR SHORTAGES!! to labor shortages? In other words, even the Beige Book, a mirror unto the Fed’s internal thoughts, describes a policy body in increasing conflict with itself for reasons that sink right down to its philosophical core.

If the Fed is notably more doubtful on wage dynamics, thus inflation, thus economy, why are so many people in the mainstream so sure that interest rates have nowhere to go but up, and that, relatedly, the economy is about to go booming again? If the Beige Book is a window into how the Federal Reserve thinks, the mainstream use of it is a window into rationalizations – “we” believe what the Fed now doubts because that is what we always wanted to believe from the very beginning, so it doesn’t matter doubts or no doubts.

The latest Beige Book published today featured just 3 instances of “labor shortage.” That’s up from 2 recorded in October’s edition, but appreciably less than the prior five. It seems far more reasonable, regardless how you might treat my anecdotal study of anecdotes, that the reason for the decrease is because there never were any labor shortages apart from individual cases due to idiosyncratic factors. That’s simply because the economy isn’t what the unemployment rate says it is, or has been, and that some subset of policymakers is increasingly uncomfortable being so certain all these markets have it all wrong.

The Beige Book is another instance of Japanification denial, but one that is progressing rather than entrenching.

Stay In Touch