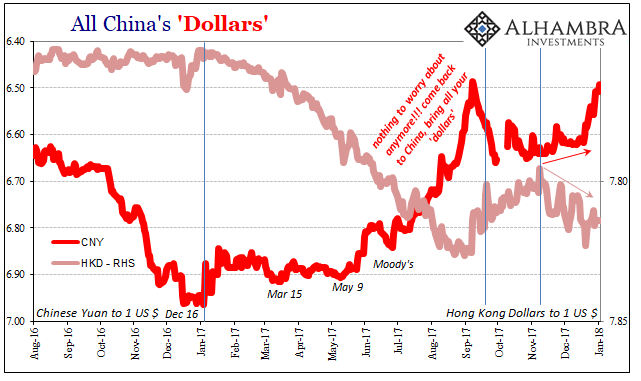

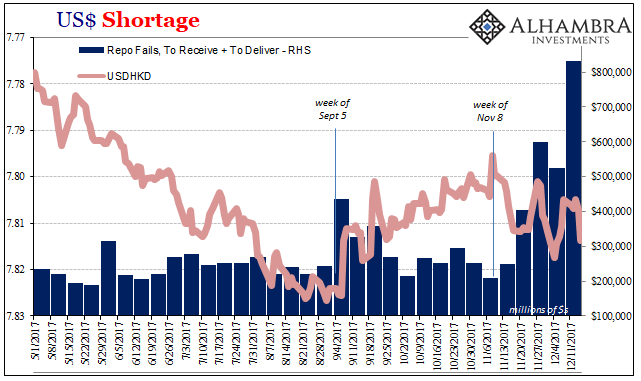

While the Western world was off for Christmas and New Year’s, the Chinese appeared to have taken advantage of what was a pretty clear buildup of “dollars” in Hong Kong. Going back to early November, HKD had resumed its downward trend indicative of (strained) funding moving again in that direction (if it was more normal funding, HKD wouldn’t move let alone as much as it has). China’s currency, however, was curiously restrained during that time.

No more. Since the middle of last week, CNY has been sharply higher. All those “dollar” balances that were surely sitting in Hong Kong perhaps just waiting for year-end were moved almost all at once.

Why the rush?

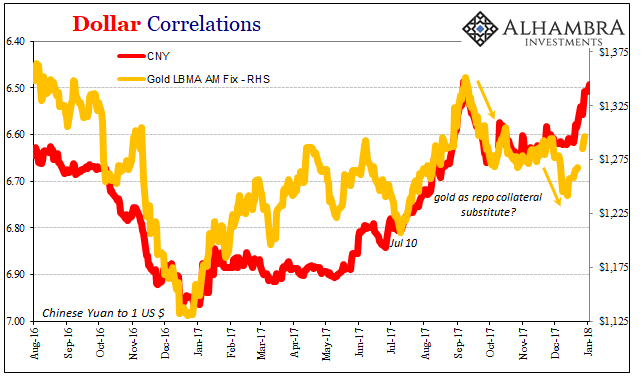

Maybe there were some government concerns for those end-of-year activities in eurodollar markets that were clearly pushed askew by what’s going on over there across the Pacific. I’m not aware of any official deadlines or regulatory requirements that would have condensed the “dollar” flow into such a tight calendar space. It looks instead to have been related to market conditions, particularly since CNY wasn’t the only big mover during that time.

Gold, which fell off another (“dollar”) cliff in early December almost surely as a collateral substitute to UST repo, regained those losses in just those same four trading days (including today) coincident to CNY’s sharp climb.

While there is no official reason for the hurry in obtaining what was being stored in Hong Kong, unofficially there is always hinted official pressure for getting each and every calendar year off on the right foot. It’s not just China’s looming New Year Golden Week, January is always prioritized (technocratic Communism) in how things work for the Chinese.

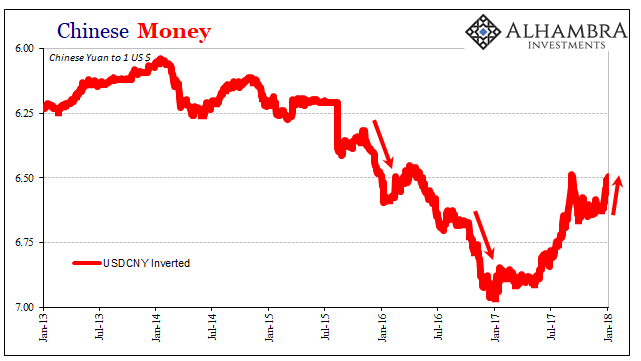

They tend to front load almost everything, and given what CNY has done each of the past two Decembers there was no interest in even the slightest hint at repeating them. It’s the usual signature of China’s official sector including the PBOC – overdo it just to make sure.

The urgency is not just financial or monetary perhaps more so economic. Despite mainstream rhetoric, China’s economy refuses to accelerate in a manner more aligned with how it is described. That sets up a dangerous dichotomy between expectations and reality (assuming that economic participants listen and pay close attention to the narrative).

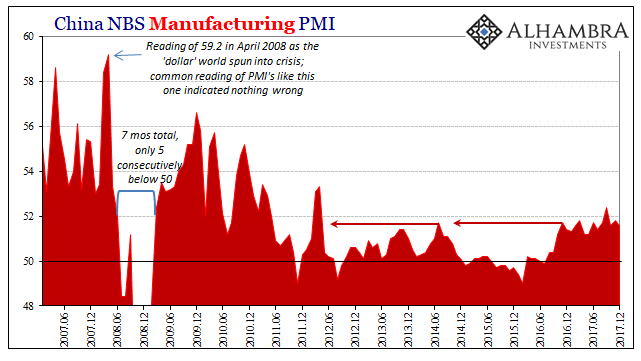

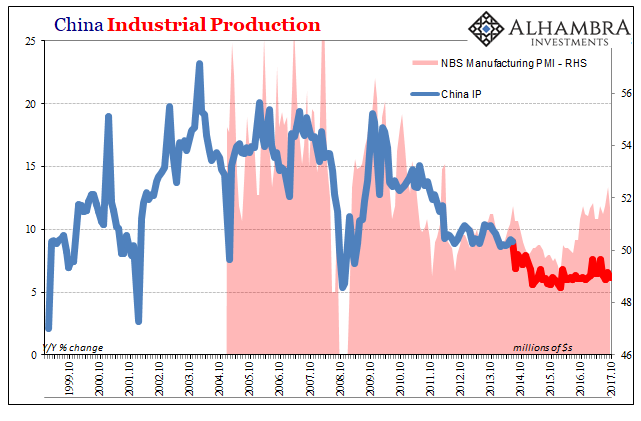

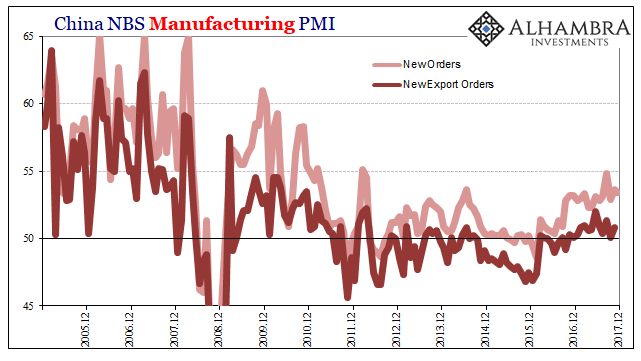

China’s official PMI’s, for example, register an unmistakable plateau in that country’s rebound from the global 2015-16 downturn. Try as they did in fiscal spending (FAI) and all sorts of monetary experimentation (aimed at CNY more and more exclusively as the year lingered on), by midyear whatever momentum there might have been from 2016’s “reflation” was exhausted.

Further, like sentiment (soft) data here in the US as well as in Europe that plateau is significantly better than the one described by more direct (hard) data. This near-universal discrepancy suggests that very danger of more unrealistic economic expectations even though those expectations aren’t all that positive in context.

This applies across industrial sectors in China, including for the export piece where sentiment about “global growth” synchronized or not remains subdued. From the (soft) Chinese perspective, economic agents may be feeling better for whatever reason but it isn’t manifested in the current economy. Hope for the future isn’t nothing, of course, but after enough time waiting for nothing other than disappointment it can end up as a more severe negative factor.

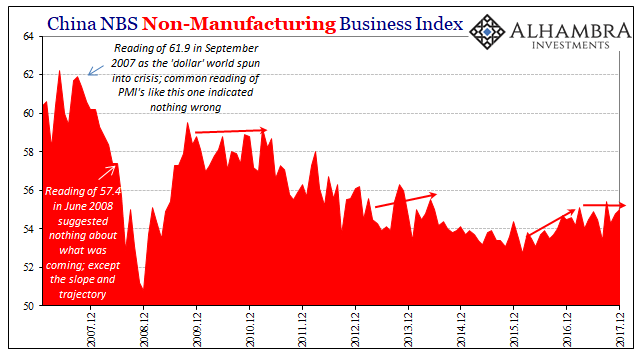

This is true not just of China’s manufacturing segment, but also in its services economy. The consumer base is being counted on to pick up the awesome slack from China Inc.’s formerly robust baseline. The level of the NBS’s non-manufacturing PMI, however, isn’t even back to where it was in 2013-14 before the last downturn.

In other words, if there is some great anxiety as to making sure CNY doesn’t falter right now or anytime soon, the best-case view described by the PMI’s appears to suggest why. Chinese officials in that sense are surely utilizing the Western orthodox textbook in playing for time. The game is aimed at confidence, to assure these very economic agents they won’t have to worry about sudden and devastating (“dollar”) currency disruptions anymore.

The Economics textbook all these central banks share, though, doesn’t include a chapter on credibility failure in large part because it doesn’t have one about eurodollars, either. The Chinese are at least aware of the credit-based nature of the “dollar”, but given their position what good is that knowledge in the face of determined Western ignorance?

The best they might hope for is something like random good luck; that with a stable CNY, artificial or not, the alleviation of currency risk will be enough to push China’s economy out of persistent (and politically dangerous) doldrums.

The problem with that approach is that it assumes the current “dollar” baseline of “reflation” will remain applicable going forward. The bigger problem is that even the “reflation” monetary baseline is for the global economy as a whole an ongoing drag or anchor. Therefore, whatever Chinese officials might hope for this “synchronized global growth” to contribute amplified by a stable currency regime is now through all of 2017 way behind.

I think that explains the rush.

Stay In Touch