At every discipline human beings have ever conceived, a fresh face or new look is almost always welcome whenever it reaches the inevitable sticking point or true rough patch. We have a word for such people in the 21st century, as an entire industry of consultants has sprung up to provide just such an outside perspective to organizations or endeavors facing grave difficulties. It’s so simple, yet often incredibly hard made so by more than anything institutional inertia.

Even the government will look to these people (not all of them are cronies, though it’s really impossible to tell just how many might be). Those on the inside often have interests that prevent them from seeing anything other than those interests. The whole problem then becomes inexorably linked to something like a determined status quo, at least until the issue becomes big enough to break through the ideological bubble.

“When crisis strikes consultants are called. Consultants thrive on chaos,” says Tom Rodenhauser, managing director at Kennedy Consulting Research & Advisory, which tracks the industry. “When a municipality is facing huge budget issues, and they can’t solve the problem themselves, they’ll call in consultants and make the tough choices that either politically or practically elected officials can’t make.”

Why can’t Economics ever seem to change to fit the actual circumstances? Noted earlier, Economists keep beating their dead horse of interest rates have nowhere to go but up even as the market for yet another year vehemently disagrees (yield curve shape more than anything else heading into 2018). The implications of that disagreement are extraordinarily profound.

The answer to the above question is awfully simple. In trying to figure out what’s wrong, Economists turn to – Economists. It has evolved into this weirdly insular process whereby there is nothing other than a positive feedback loop from which the discipline just will not be able to escape. Any system caught in such a self-reinforcing mess requires heavy outside influence to get out of it, which is often where the consulting business comes in.

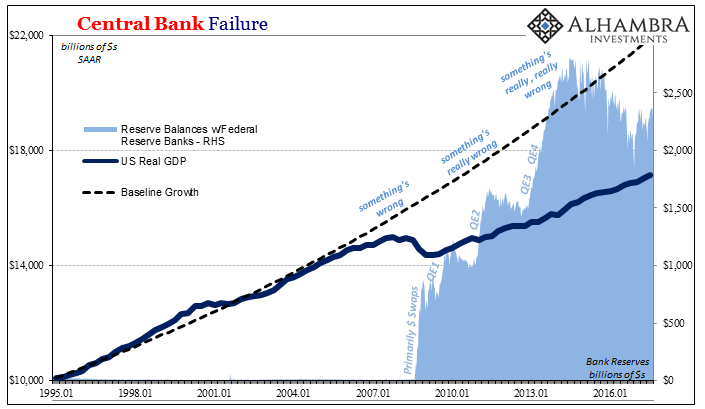

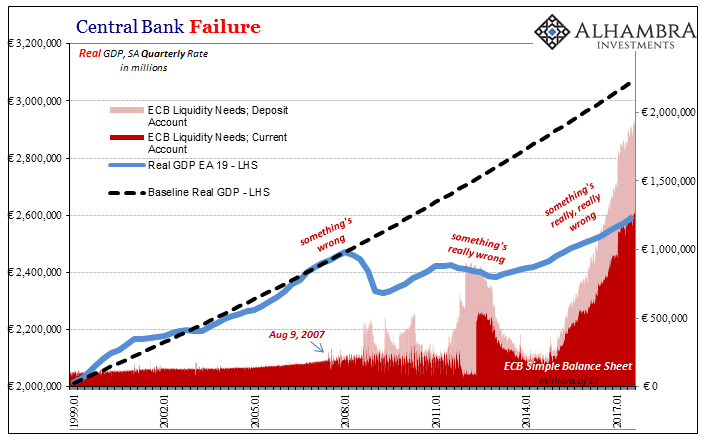

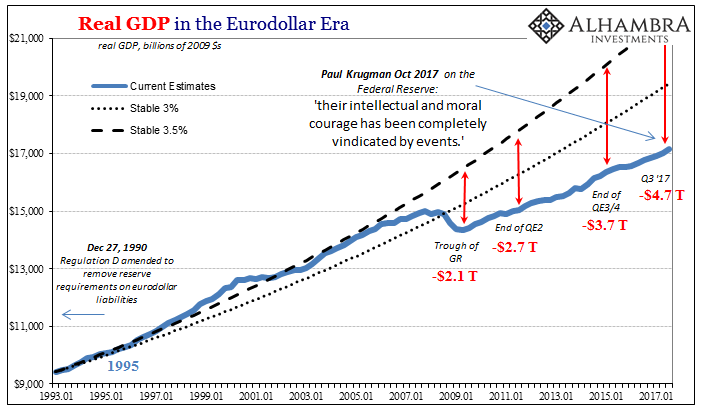

Economics, however, refuses anything but its own people. They know that “something” isn’t quite right (and they call it different things, like a zero or negative R*, secular stagnation, but all arriving eventually at the same point of a global economy without a recovery even after ten years of their best experimentations) but in trying to parse what it might be they look only to each other to offer slightly different versions of the same thought process. All the same foundation premises remain constant, with never any serious challenge to them.

On January 8, for example, the Brookings Institute will hold an event (thanks T Tateo), a sort of a debate about whether the Federal Reserve should think about altering its 2% inflation target. The reason they might pursue a change in strategy is obvious, meaning their failure (for five and a half years, and counting) to meet their current one.

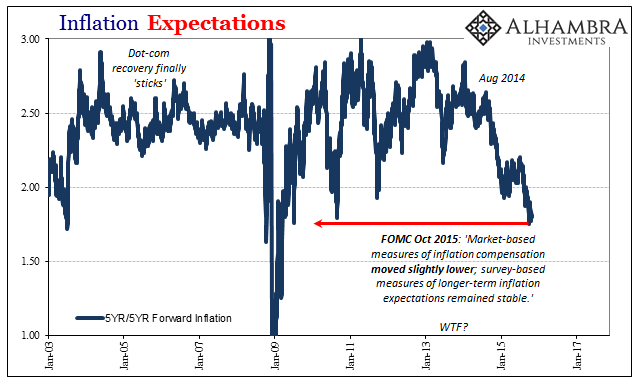

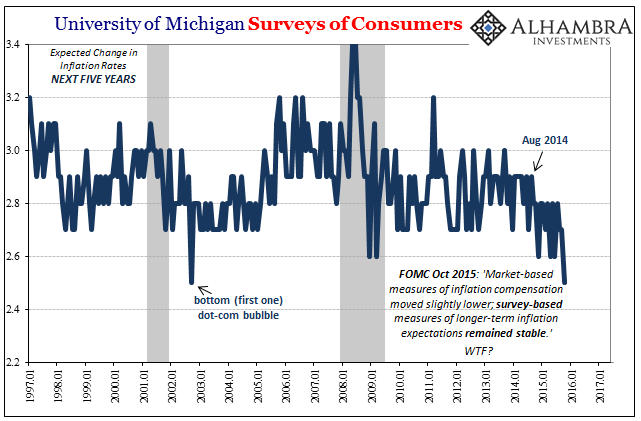

Rather than lower it as maybe you might expect given the prolonged (the appropriate antonym of transitory) undershoot of calculated consumer price indices, these Economists will argue (some of them) that monetary policy should shoot for an even higher number. The basis for that position is inflation expectations, or really a clear drop in them, that for years official policy denied had ever happened.

To counter what is really market expectations (as well as consumer surveys) no longer so attached to central bank policies, more Economists are starting to believe that central banks should do even more; the same things, of course, like promises to do whatever monetary policy “stimulus”, only now with a higher target attached.

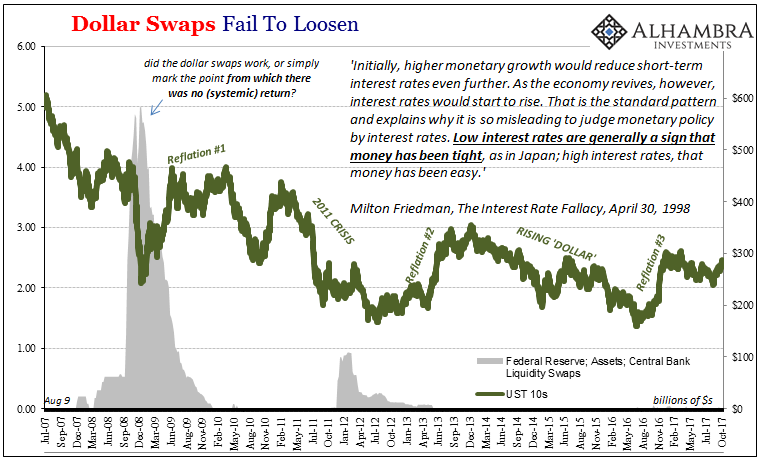

This magic number theory never really gets off the ground, however, because no Economist ever really examined the full range of possibilities as to why the current target hasn’t been met. The simplest, most direct explanation for lack of inflation follow through is, of course, the effective monetary condition itself. Milton Friedman proved long ago that persistently low interest rates are a product of “tight” money not central bank “accommodation.”

But Economists are prevented from acknowledging established reality because they are wed to QE and monetary policy in each and every operation and format. For them, there is no possible monetary explanation for the problem, which means so long as they only discuss among themselves they will never, ever figure it out. The active preclusion of outside voices in the official discussion and the attendant enforcement of the rigid ideological bubble it leads to is just as much to blame as eurodollar banks only shrinking their money dealing activities, indeed their whole collective balance sheet. The latter could have been, and still can be, handled if only the former wasn’t the case.

And just who has the Brookings “debate” scheduled for its line up? Five Economics professors from the usual major universities, three Senior Fellows from mainstream think tanks (including Brookings), two current Federal Reserve officials (both branch Presidents), one former (Bernanke, of course), and another central banker retired from the Bank of Canada. Differing views? Not on matters of actual importance. Thinking outside the box? They can only ever be the box.

Out of the whole roster for that highly if academically distinguished group, there is only one who works at a global money center (eurodollar) bank. Deutsche Bank’s Peter Hooper is slated to talk about monetary policy, which might seem a welcome unfamiliar voice if only he wasn’t that firm’s Chief Economist.

Nothing has changed because for the time being nothing can. I used to believe that Japanification was all about zombie banks and asset bubbles because that was how it has been told (funny how almost all global banks over the last ten years now appear and act very much like zombies). Looking more closely, however, what you find is that the real problem was always Economists who use nothing but Economics and the Economic opinions of other Economists to try to decipher what’s really wrong; always, always failing to do so because the issue is Economics itself.

As now the US and global economy follows along in Japan’s unfortunate path, what is again the common denominator?

Stay In Touch