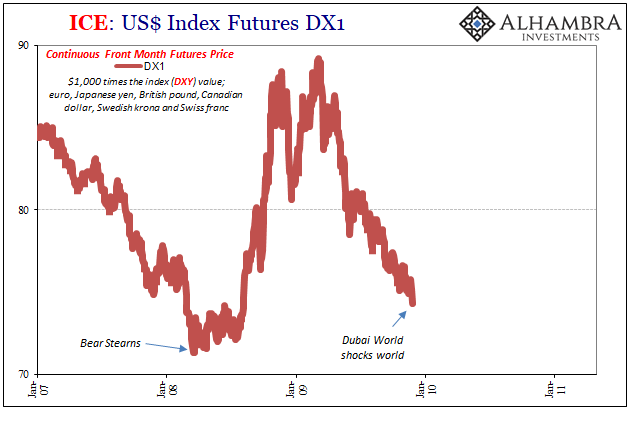

On November 29, 2009, the government of Dubai shocked the world with a statement acknowledging trouble with its debt load. Dubai World, a government-owned conglomerate that was the conduit for the country’s oil-fueled debt extravaganza that had literally transformed the nation, asked for a “stand still” from creditors in order to extend maturities until May 30, 2010.

It came while the financial system was still in a state of shock, where uncertainty was actually the best case. The global economy was starting to look like it had found its bottom after the ravages of a worldwide “recession”, but with so much still in question further problems that might develop were given unusual scrutiny. That was true especially of what otherwise might have been small issues.

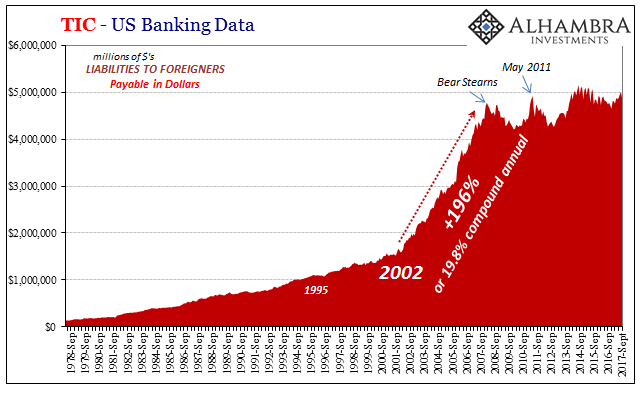

Dubai, though a major oil hub, had they run into similar problems a few years earlier would barely have made a dent in the financial system’s consciousness. The operating paradigm before the middle of 2007 was risk at all costs, largely because it was viewed there weren’t any real costs (over time).

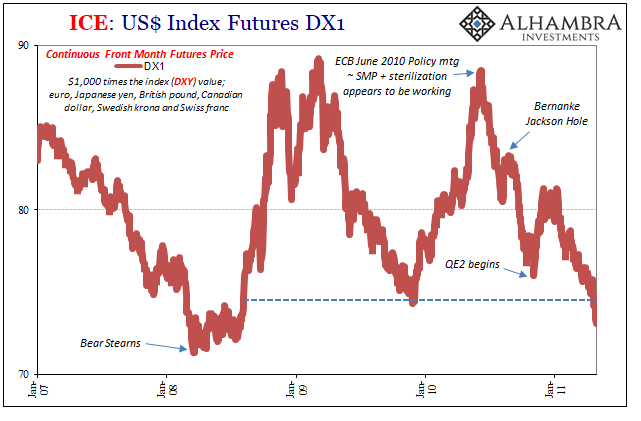

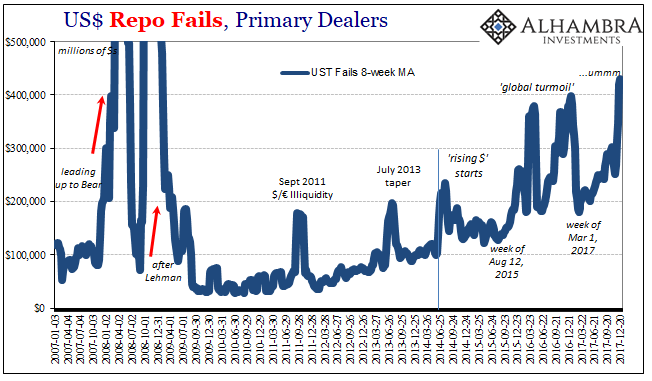

While there was much to be rethought after August 9, 2007, the day the funding system changed, the full paradigm shift probably didn’t really start to take root until the failure of Bear Stearns in March 2008. From that point on, the potential cost of risk was displayed for everyone to see; and it was much more than trivial.

As noted last week, for authorities, particularly monetary officials, Bear was treated as the end, the final act of a small mortgage crisis largely contained by the Federal Reserve’s belated but good work. In many ways it has proved to be the end, just not at all in the manner anyone had expected.

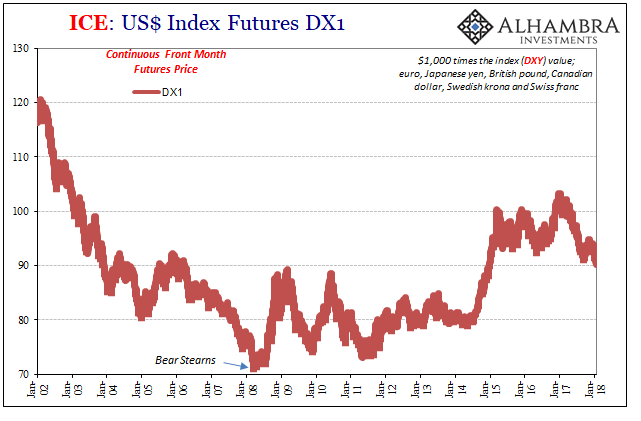

Take the “weak dollar” that had prevailed previous to the failure. It had become the wink and nod de facto policy of the Bush administration, complicit with the Federal Reserve and its ultra-low interest rate policy to push the exchange value of the dollar lower in order to stimulate American growth and economy despite its strong dollar official commitment.

Wrong.

Bear did prove to be the long-term end of the weak dollar, but for very different reasons starting with the “weak dollar” itself. If we instead view the period before March 2008 as one having an abundance, even over-abundance, of dollar (really “dollar”) supply, then the reverse in a rising dollar would be constrained supply occasionally to the point of general, broad liquidity issues. Maybe even a global “dollar” run or two.

That’s why Dubai’s news was so profound. A lot of what passes for a panic or run is emotion, which is why economists decided in the thirties to take money (gold) out of the public’s hands so that the system would never, they believed, be at risk for a repeat. But by the end of 2009, it had become clear that in this case it was interbank markets, and thus profession banks staffed (to the rafters) with professional economists and mathematicians, where all the emotions had run wild. It was bank panic of only banks panicking.

From March 2009 to that point, it had appeared more and more as if it all might have been over. Market prices were returning to normal, or at least heading in the right direction more forcefully. Even the dollar was falling, a signal everyone thought meant what everyone thought was the governing dynamic. In other words, the return of the falling dollar seemed to act out where the Panic of 2008 was just a temporary interruption. With the crisis moving toward successful conclusion, the global economy could get on with recovery which for conventional wisdom meant going right on with life as if it was 2006 again.

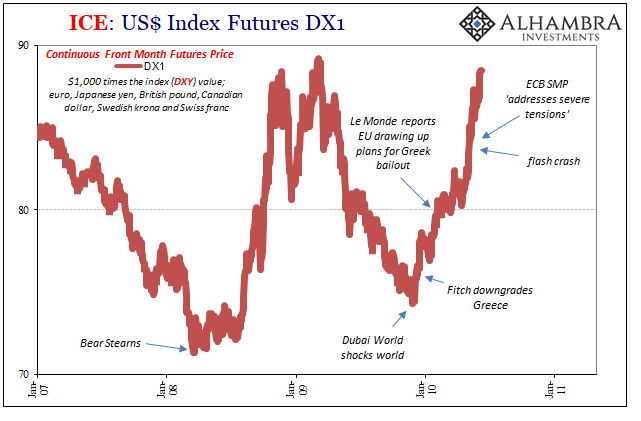

Of course, the world was forced to react to more than Dubai World. Just days after that, news came of increasing difficulties associated with Greece. Once more, another small country threatened to do far more damage than one small country should ever be able to accomplish. Because so much came out of these small starts, it was a warning that the system was still raw and remained in a highly precarious state closer to lingering dysfunction than full recovery.

The falling dollar, even as in late 2009 it had appeared all but certain to drop out below the low set at Bear, suddenly, sharply reversed course. The dollar screamed higher once more, and it was totally unexpected.

Along the way, over the next few months in early 2010, “we” found out that there was a lot more going on than just rumors of maybe some possible problems in far flung, outlier locations. It dawned on some that there was a nontrivial chance the Great “Recession” was perhaps much more than a harsh but transitory intrusion. It may have revealed deep, structural cracks right down to the economy’s (monetary) foundation.

By early May 2010, US stock markets were shocked by a “flash crash” that in the mainstream appeared to have come out of nowhere. But it wasn’t out of nowhere at all, it was a symptom of systemic illiquidity punctuating an escalation, or acute downside variation in that trend. It was so severe that it forced the ECB barely a year after what was hoped to have been the end or bottom to start buying (and sterilizing those purchases) several OECD sovereign issues – those bonds believed to be “risk free.”

At its June 2010 regular policy meeting, the European Central Bank suggested that the SMP, by then not even a month old, was working. What followed has become an all-too-familiar pattern, one that efficient markets would have noted in advance. These inefficient markets, operating instead with under a huge degree of uncertainty (not the least of which was due to the fact that it appeared authorities had no idea what they were doing, and, worse, that they might not have any idea what was actually going on, both possibilities than ran directly against what everyone in this business is taught from the first day of Econ 101 – don’t fight the Fed!), was still predisposed to give monetary policy the benefit of the doubt.

For the dollar in late 2010, particularly after QE2 in the US, everything headed back toward “normal.” Falling once more, the dollar index (DXY) even dropped below the prior low set back at the end of November 2009, by that point already a year and a half distant. As is always the case with such comparisons, it was trumpeted and heralded as a significant milestone. Everyone loves to hear about a multi-year breakout because it seems like it should be significant, substantial, and meaningful. Multi-year.

And there was a great deal behind the move, too, beyond simple policy expectations. Outwardly, there was a lot going right on the surface. Inflation expectations were rising, as was inflation. Commodity prices especially crude oil were up sharply in recovery, forcing some like the ECB to worry more about overheating than lingering weakness (they “raised rates”, believe it or not, twice in 2011). Economists were certain that better days were just ahead after a small and transitory interruption that by 2012 would have been forgotten as another footnote in the burgeoning chronicles of monetary policy genius.

It didn’t quite work out that way, of course, largely because it is assumed that the dollar is the thing. It isn’t. The dollar is moved by the eurodollar, the stuff that goes on hidden in the deep recesses of the shadows. Nothing goes in a straight line. Throughout both of those falling dollar periods (2009, 2010-11), and even as the dollar kept falling in late 2007 and early 2008, it was pricing “normal” when in the shadows there lurked anything but.

Eventually those that start out as obscured shadow problems become unobscured, forced to the surface by whatever, even the seemingly small events or changes that in a healthy system otherwise would have left no imprint at all. It’s only at those times when the eurodollar becomes the dollar again, the sudden shock of its unanticipated, never expected rise.

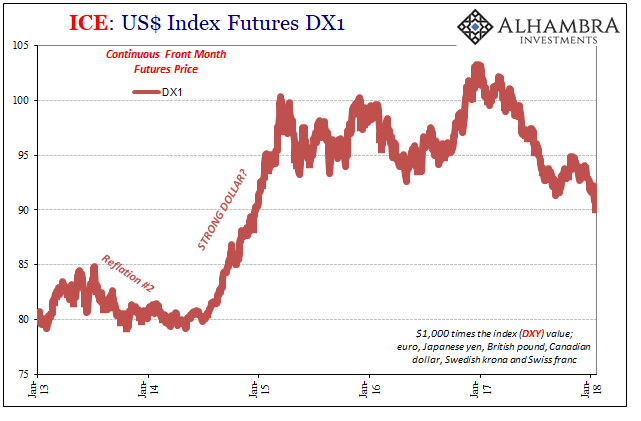

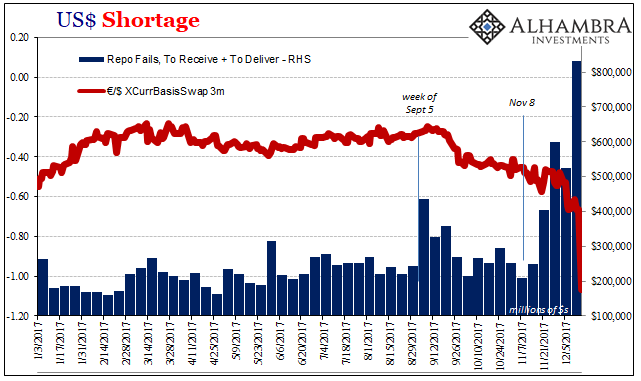

Since the start of 2017, the dollar has been falling again. Inflation expectations are on the rise, slightly, as are inflation rates (compared to consumer prices during the 2015-16 downturn). Commodities are up, including WTI. Economists are all over the internet once more talking about a boom and how better days are just around the corner. Normalcy at last.

With DXY breaking down to 90, the lowest level in years, people are asking, “is the market finally buying it?” I think it depends on which market you are talking about, those often distracted by the light or those sunk deep in the shadows.

That doesn’t mean that DXY and other dollar indices won’t keep falling; they very well might break new multi-year lows just as Treasury yields at the long end break multi-year highs. In both cases, these prices/indications/rates/yields are being moved by what is seen with only some occasional reference to what isn’t (more so in UST’s than DXY). It’s the stuff that isn’t that gains my attention not because it could push the dollar index up tomorrow in a hard reverse, but because it suggests the chances of another “rising dollar” shortage or squeeze are far higher than trivial – those times when suddenly ignoring the shadows becomes impossible any longer.

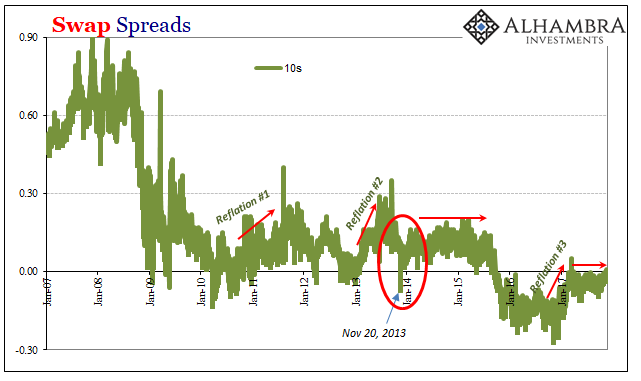

And we won’t know what small, seemingly nondescript thing does the trick. What turned it all around in the middle of 2014? It could be anything, even the stock market (blow off top?).

In broad terms, nothing has really changed except these intermittent periods where in the media all the experts are convinced that something has. Behind it all, in the background of the shadows, the system remains the same, stuck largely in the same shape as back when just about ten years ago Bear Stearns shocked the world by failing under a falling dollar.

Stay In Touch