The Federal Reserve is ostensibly an independent agency of the government. Already it is beset by a contradiction. How can it be independent if it is otherwise an arm of the federal structure? It’s a problem beyond mere perception that officials have struggled to overcome since its inception.

Between the Banking Act of 1935 that restructured the central bank in the wake of its biggest failure (the very thing it was created to avoid) and 1951, the Fed was a literal rather than figurative part of the Treasury apparatus. It was obliged to, among other things, buy government debt first for WWII so that the federal budget was never at risk over interest rates.

In 1951, FOMC officials sparked a minor controversy by refusing to keep to its UST ceiling, that is to buy all the government bonds in the market required so that yields never rose above the expressed threshold. Treasury eventually backed down, which created this myth that the Fed “won” for a second time its independence.

The issue is degree. Disagreeing with a Treasury policy and acting in defiance of it does not necessarily constitute full political detachment. On the contrary, the central bank and that part of the federal government have maintained a close working relationship for a century apart from one minor episode.

In 2018, it’s not uncommon to hear whispers of further collusion, meaning that perhaps rising interest rates will motivate the Federal Reserve to act on behalf of the government in keeping interest rates low for as long as possible. Some even argue that is why the FOMC has taken its time in normalizing monetary policy, a coordinated effort to keep the budget from being exposed to potentially massive interest costs in the future.

I see no evidence for this, nor does it appear to be, or have been, a constraint on federal spending before now. The independence of the Fed is much more about the basic ties it shares with the rest of the bureaucracy. What they all have in common is a common belief in technocracy.

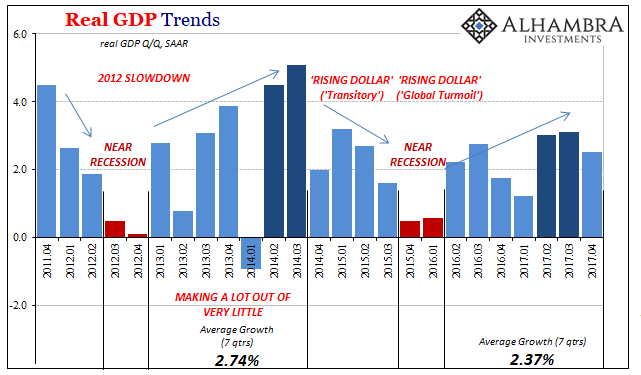

Three years ago, in January 2015, when prospects for economic recovery were far more advanced and even immediate compared to now, policymakers at the central bank took a more reasoned approach to conditions. Yes, everything was looking good and they were happy to express confidence, but they were also careful in suggesting what was missing that perhaps shouldn’t have been. They were cautiously optimistic with maybe a skew to optimism but restrained nonetheless by very real challenges.

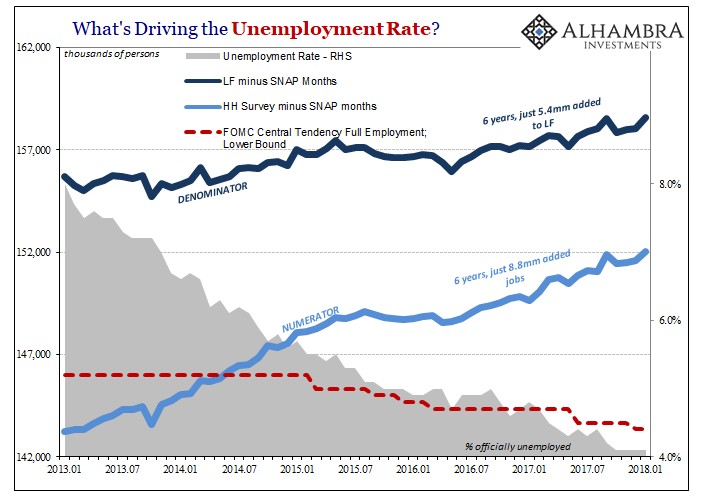

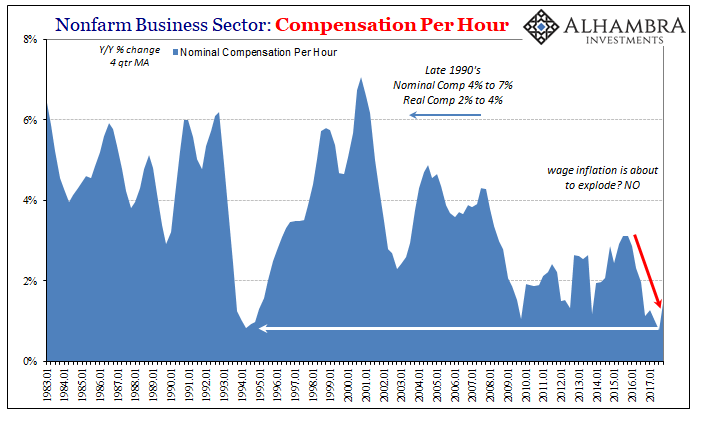

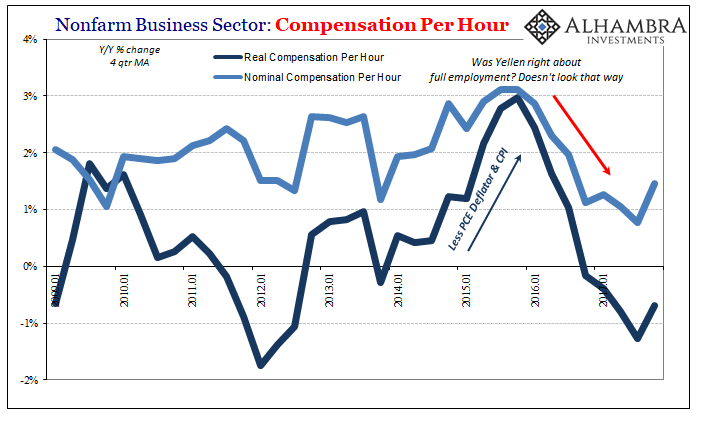

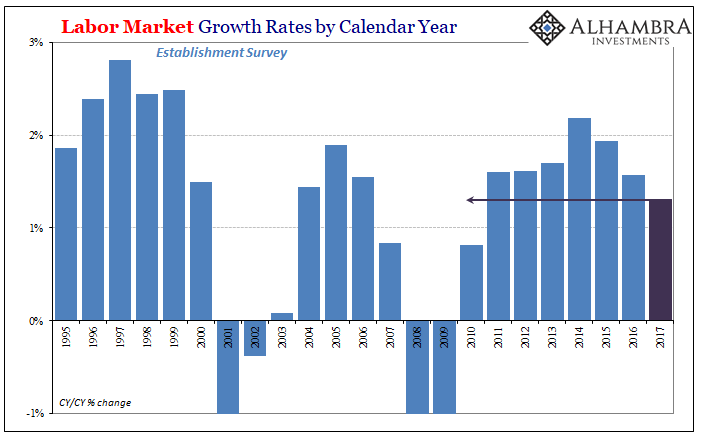

At the top of that list was wages. The unemployment rate by that time had already dropped far and fast. At 5.7%, it was just at the upper bound for what the central bank’s quantitative models suggested for “full employment.” This was for these economists no trivial distinction; full employment is the end of slack and the beginning of an inflationary environment.

Wage-driven inflation, however, doesn’t just appear at that boundary; it begins to show up months or even longer before. By the time the FOMC gathered in January 2015 to discuss monetary policy and the recovery’s evolution, there was still no wage growth in sight. The lack of acceleration, they admitted, would be a huge problem:

…and that tepid nominal wage growth, if continued, could become a significant restraining factor for household spending.

In addition, a few participants suggested that the weakness of nominal wage growth indicated that core and headline inflation could take longer to return to 2 percent than the Committee anticipated. In contrast, a couple of participants suggested that nominal wage growth provides little information about the future behavior of price inflation.

At best, the Committee was confused; at worst, conflicted.

Three years later, wages still have yet to budge. In several key metrics, compensation growth is significantly less today than at that time.

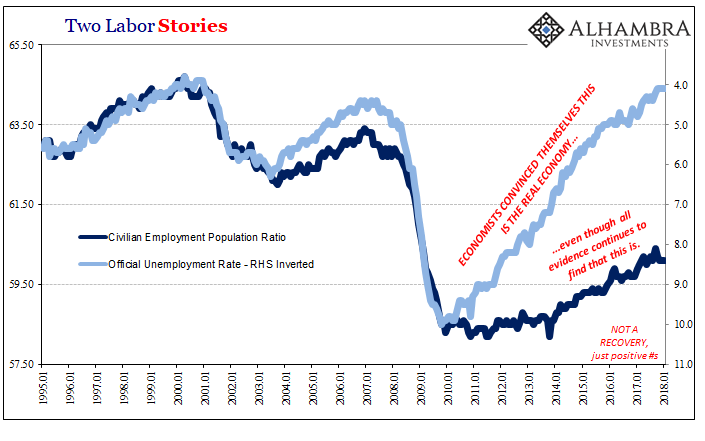

If they were cautiously optimistic about the missing wage growth in early 2015, by early 2018 they were downright skeptical, right? If anything, the FOMC seems even more convinced despite still some quiet objections.

During their discussion of labor market conditions, participants expressed a range of views about recent wage developments. While some participants heard more reports of wage pressures from their business contacts over the intermeeting period, participants generally noted few signs of a broad-based pickup in wage growth in available data… That said, a number of participants judged that the continued tightening in labor markets was likely to translate into faster wage increases at some point.

At some point? This is data dependence; three years later and at some point it will change? That plus, of course, the staple of irrational hope, this constant supply of anecdotal labor shortages. These continue no matter that “participants generally noted few signs of a broad-based pickup in wage growth.” That’s actually putting it charitably; there are, in fact, no signs of a pickup and quite a few key series pointing, again, in the other direction.

What’s happening here? It seems somewhat of a mystery as to how the Fed could have taken a more reasoned approach in 2015 when things were then so much better (looking behind, as always) compared to now when the economy is by every measure substantially worse.

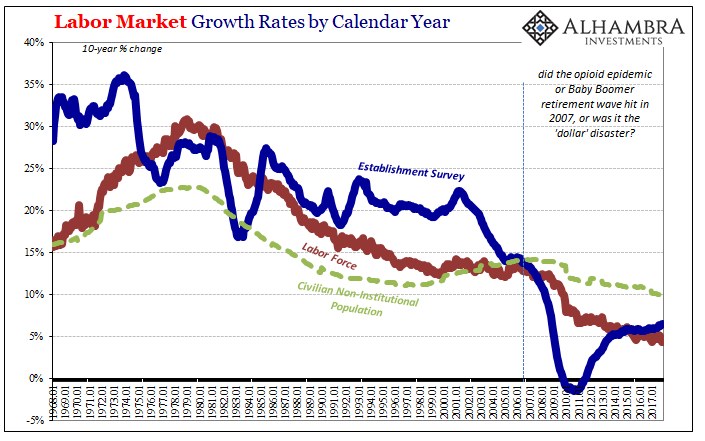

The difference between 2015 and 2018 was 2016. The political landscape evolved in such a way that what occurred was perceived as a threat to the way things are done – as it should have been. The election of Donald Trump as well as the British decision on Brexit (along with similar results from several other less notable if still important hustings) showed that dissatisfaction had built up long enough that it was finally breaking out. Lashing out at the Establishment, whatever that may be at any one time, continued voting along these lines risks eventually a full and comprehensive house cleaning.

It is here, I believe, that the Fed’s independence is called directly into question. Rather than remain true to the scientific pursuit of economics, and ultimately the well-being of all those who are expressing their grave, and quite legitimate (as the wage debate clearly shows), economic dissatisfaction, the central bank has in many ways circled the wagons with the rest of the bureaucracy.

It hasn’t been a direct assault on the populists who are gaining ground as the face of voter angst, instead it has been this parallel attempt to discredit their very legitimacy. In the case of the Fed, as well as all the other central banks (except, ironically, the PBOC), they continue to contribute the BS you see quoted above. The economy is awesome, they claim, and you’ll see (at some point).

Independence is not with whatever part of the government you choose to work, or to which specific functionary you might eventually report to, or whose ass you have to kiss to get the job in the first place, it is being true to the republican (small “r”) ideal of working on behalf of the people. Americans are being screwed by Economists who care more about staying on top of political influence than actually allowing full recovery to happen. Data dependence.

The technocracy is given full internal commitment and external endorsement above all else. After what happened in 2016 when people finally started to voice their limit, that has meant more confidence and declarative stances even if what they contain is utter nonsense, total rationalization.

The global economy didn’t just forget how to grow in 2008. But that’s what we’re being told to believe. Never mind the big panic and all that huge fuss over money and banks, Baby Boomers are retiring and middle America is drugged out and lazy. And despite all that, in the end, it’s not really all that bad anyway. Wages and inflation, even a friggin’ full-blown boom, that’s all set to begin. At some point.

Stay In Touch