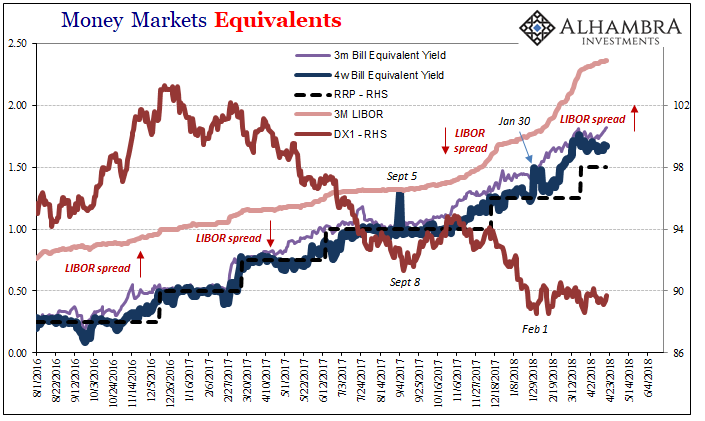

If we are analyzing funding risks of late, which is a perfectly natural thing to do given where things stand, we shouldn’t only focus on the technical aspects. Sure, there is LIBOR-OIS and all that jazz in Hong Kong. But there are other quite simple components to consider, too.

If there is a cycle to these upturns and downturns, each separated by “dollar” events in between, it has become a lot like Groundhog Day. I don’t mean the classic movie starring Bill Murray at his best, rather the actual February holiday. Banks at or near enough the conclusion of each of these episodes tend to turn more optimistic. They are practically programmed to be that way given how Economic forecasts are set at the Federal Reserve and then parroted uncritically all throughout the system.

In other words, they are predisposed to always skew positive. The times when optimism seems most realistic are in the early stages of “reflation.” Like Punxsutawney Phil, they come out of their holes, extend a little bit of risk, and then await the sun’s verdict. They never expect to see their shadow because the Fed always predicts good things; but have become jaded enough (post-2011) not to pull out all the stops.

That’s why “reflation” starts out tantalizing each time but never gets too far into full-blown recovery. Ultimately, the economy never lives up to the hype which means any additional risk put on during “reflation” must be reassessed in light of another disappointment. Banks see their shadows and scurry back into their (balance sheet) holes.

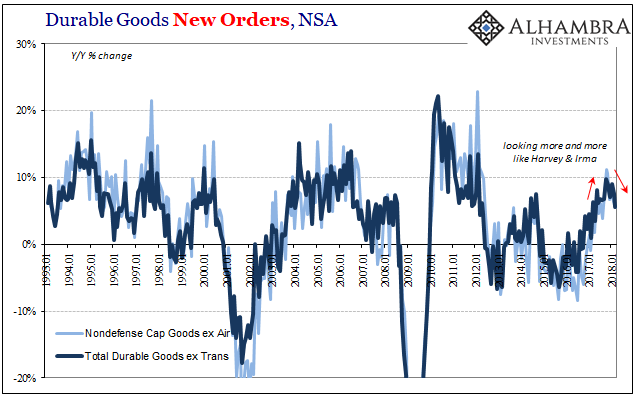

The timing of this latest rerun is instructive. For several months last year, the global economy appeared to be topping out. Then came the big hurricanes Harvey and Irma. The end of 2017 finished with a flurry of big activity, or at least what looked to be acceleration in comparison to the last six years of depressed highs.

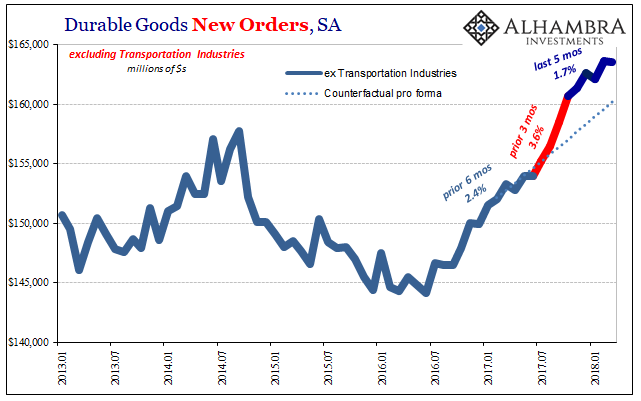

Inevitably, those temporary effects began to disappear toward December and the start of 2018. As economic stats come back down to look too much like last year and other years, the funding groundhog has to accept two unappealing options; that the apparent strength of those months was just a collective tropical-driven aberration; or, even if it was organic acceleration, it is now disappearing all over again. Neither is particularly palatable toward further risk.

Banks counting on “globally synchronized growth” to pan out would quite naturally become increasingly shy for a fourth time.

The latest report for durable goods is not by any means definitive. It does strongly suggest the hurricane view, however. For several months, growth in new orders and shipments for long-lived goods was approaching robust. Year-over-year increases closed in on double digits, which would have been a minimum level to be considered consistent with economic health.

In March 2018, new orders for durable goods (excluding transportation industries) rose by 5.5% over March 2017 (unadjusted). Shipments gained just 5.4%.

The seasonally-adjusted series shows the distortions more clearly. In the six months prior to Harvey’s landfall, new orders increased a lackluster 2.4%. August through October 2017, in just three months orders were up an almost impressive 3.6%. Since, they have gained not even 2%, a rate of growth less than before the storms (as some activity was surely pulled forward).

In short, the economy doesn’t look to be accelerating at all. And if it was at one point last year, it doesn’t appear to be any longer.

In monetary and financial terms, economic growth is opportunity which is the whole reason for taking risk. If it turns out that there is at best no change in economic circumstances in 2018 from 2017 (or even 2016), that is yet another negative factor in terms of setting the marginal direction for general behavior. Add on to that the continued and ongoing imbalances in the world, which “globally synchronized growth” was meant to address, and the circumstances dictate at the very least resumed caution.

Unlike Pennsylvania’s rodent, however, upon the global banking seeing its shadow yet again the global economy isn’t in for just six more weeks of stagnation winter. It means in this context, in all likelihood, yet another cycle where limited upturn shifts back toward “unexpected” downturn. It doesn’t happen overnight, this is a complex process, after all.

The good news, if you choose to see it that way, is how durable goods data is far from conclusive on the subject. Like Bill Murray’s character in the movie, one of these days we could wake up and have it actually be tomorrow. It doesn’t, however, appear that there is much enthusiasm lately to bet that way.

Stay In Touch