When the minutes of the March 2018 FOMC meeting were released on April 11, St. Louis Fed President James Bullard, a non-voting alternate member, immediately objected to one statement contained with them. According to Bullard’s version, the notation that “all participants” agreed further rate hikes were necessary was incorrect. He was and remains opposed to that contention and we are to presume Bullard voiced his protest at the meeting.

The St. Louis branch chief is among the more vocal and dovish of senior leadership. Most people recall his outlandish appearance on October 16, 2014, when everything seemed to be going wrong – including a sharp selloff in stocks accompanying that so very notable UST buying panic.

We have to make sure that inflation expectations remain near our target. And for that reason, I think a reasonable response by the Fed in this situation would be to … pause on the taper at this juncture, and wait until we see how the data shakes out in December [2014].

Many complained, or complimented, Bullard’s attempted restart of the Greenspan put at what seemed a crucial juncture for the markets. That wasn’t his purpose, or at least I don’t think it was (I can’t speak directly for him). There is far too much emphasis on share prices both inside and outside the Fed.

His “dovish” concerns were improperly couched in monetary policy, suspend taper, but ultimately his view was the correct one – the only member who was even close to getting 2015 right. Unlike what Yellen and the rest were so easily willing to overlook, dramatic market upheaval wasn’t a good sign. QE wasn’t the issue, rather it was the economic outlook particularly in looming deflationary tendencies that demanded policymakers reassess the situation.

Continuing QE wouldn’t have made any difference, but the FOMC might’ve saved itself from a lot of further embarrassment and lost credibility during 2015 – especially its first “rate hike” in a decade undertaken during near recession conditions, a downturn from which the global economy has yet to recover from.

Bullard is therefore made into an uber-dove when in fact he is nothing more than a documented skeptic. He just isn’t unconventional in his opposition. When he made those comments back in October 2014 people only paid attention to stock angle when they should’ve understood that his view was one of serious economic doubt which the rest of the mainstream never fails to turn optimistic. Dovish or hawkish is merely the frame of reference where for those rationalizing the current awful economy it can only be good; dovish = the Fed will keep “accommodating”; hawkish = the economy must be turning awesome. We can’t lose!

The current inflation debate, such that there is one given recent hysteria on the topic, falls along these same lines. Bullard is again called dovish when again he is nothing more than cynical. Given what happened to the March minutes, maybe it isn’t surprising how doubts are always downplayed. The FOMC is not data dependent, they are future dependent meaning econometric models that always forecast only the best scenarios.

The day Mr. Bullard objected to the official record, Boston Fed President Eric Rosengren was using it for the opposite purposes.

Boston Fed President Eric Rosengren said Friday that his own economic forecast and the forecasts of his colleagues on the Fed’s policy committee are “quite positive” – citing fairly strong economic growth, job creation, falling unemployment, and inflation rising close to the Federal Reserve’s 2 percent target.

“…and the forecasts of his colleagues.” All of them are “quite positive?”

Bullard’s case comes down to the academic pursuit of the neutral interest rate. Whether or not one actually exists in the real world, or whether it is nothing more than another tool with which to measure monetary policy’s effectiveness (or ineffectiveness) in an ever-changing economic world, a great deal of evidence is on Bullard’s side particularly with regard to inflation. In his view, the Fed has already met the neutral rate and therefore given economic conditions any further rate hikes may be unwarranted.

Take his argument out of the academic context, all he is saying, like he was in October 2014, is that the economy is awful and not getting any better, not really. The FOMC is, like always, projecting forward based on the same assumptions that have led them astray time and again for more than a decade.

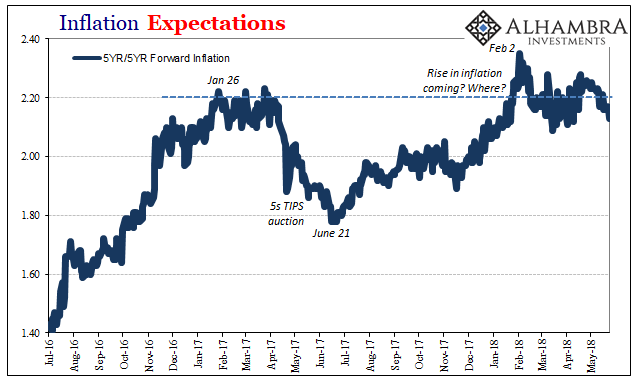

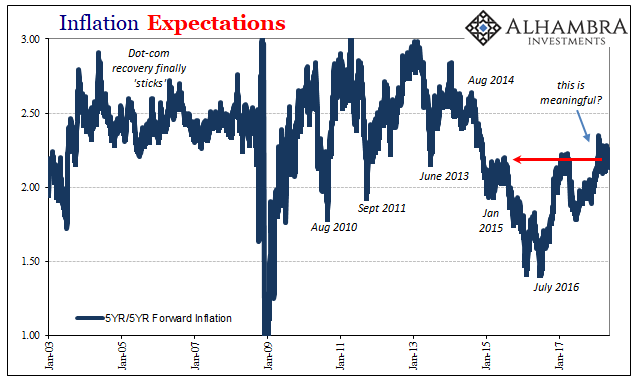

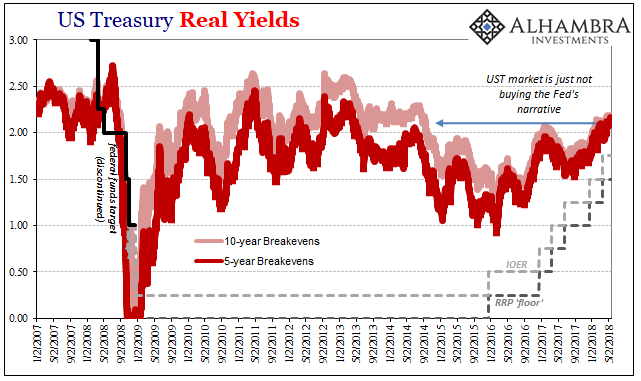

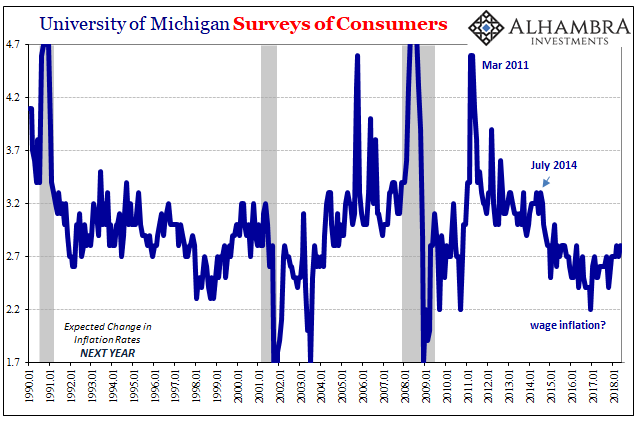

Unlike all the hawkish attention garnered by those like Rosengren, the markets and various surveys all agree with the “dovish” Bullard. Inflation expectations, for example, are up from the lows set in 2016 – but those were very low lows. Expectations aren’t up, they just aren’t down as far as they were. Importantly, they are all still down, they haven’t yet gone back to where they were in August 2014 let alone indicate something like a massive inflationary wave blown up by a hurricane of labor shortages driving the unrelenting winds of wage gains.

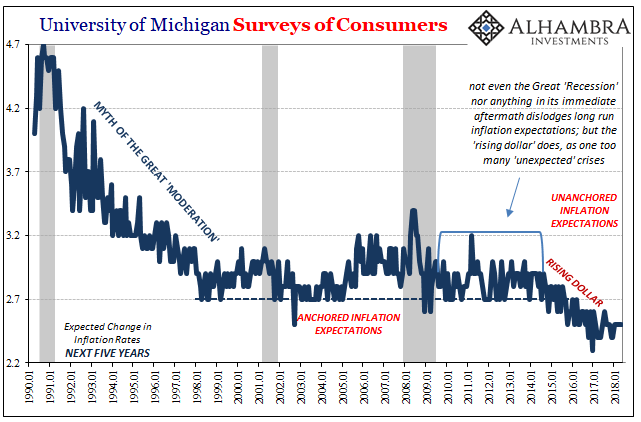

Consumer surveys aren’t buying the hysteria, either. The University of Michigan’s Surveys of Consumers continue to show even more pessimism about this economic variable than market-based views. Compared to August 2014, UofM’s surveys suggest practically no rebound at all. Expectations are currently closer to what were record lows (5-year) in 2016 than the tame expectations in 2014, and therefore nowhere near signaling a drastic breakout consistent with all the prior hysteria.

Again, it’s not dovish vs. hawkish; it is skeptics vs. fairy tales. Someday, and this day will come, the fairy tale will finally prove true. The economy will recover at some point. There just isn’t any indication that day is close at hand. On the contrary, what we find is the ugly possibility that there might be a great deal more pain to come before that can ever happen.

Stay In Touch