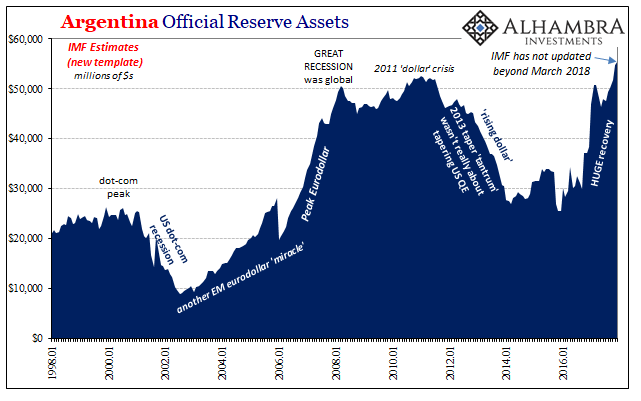

It’s amazing how in a world of supposedly separate, closed economies they all seem to congregate anyway toward the same events. In early 2000, the US dot-com bubble ran into its own contradictions, the rationalizations holding it together no longer so tempting to what was for years insatiable investor appetite. Not even a year later, a mild recession began.

What was a slight contraction in the US, however, produced massive swings in economic fortunes elsewhere around the world. In Argentina, for example, the country had remained in serious disarray but afloat nonetheless for years. By the end of the year 2000, coincidentally, the situation had changed beyond the country’s ability to influence.

In came the IMF. In December of that year, Argentina was provided what the organization itself characterizes as “exceptional access.” As the situation continued to deteriorate, by May 2001 an internal review still held out chances for success. In September, their rescue was augmented even though the Argentinian government wasn’t in compliance with many (perhaps any) of the original terms.

By December 2001, at the end of the US recession and just a year after its first involvement, despite so much bailout dollars already spent the IMF pulled the plug and left country to its ultimate fate.

Fifteen years later, Argentina was back. A new government had been elected promising to do all the things required to erase the faults of that past. The nation became a darling for global markets in 2016, its government officials having transformed themselves into the world’s best and most successful bond salesmen perhaps ever.

This is a key distinction, as a I wrote a little more than a month ago at the start of negotiations over what has now become another IMF bailout.

Argentina was perhaps the biggest success story of “reflation.” Left for dead in global markets as the hammer of the “rising dollar” pounded down on everyone, the country elected new leadership and began taking the right steps toward modern economic integration. That’s the story, anyway.

What really happened was a bit different. The country that had been funding itself at the mercy of global eurodollar banks switched to funding itself at the mercy of global eurobonds. Good choice in 2016. 2018? Bit of a different story.

Bit of an understatement, too. Under immense “dollar” pressure for reasons nobody seems to be able to explain, the IMF this week agreed to hand Argentina the largest single bailout in history. An unthinkable $50 billion has been committed, with supposedly $15 billion made available immediately.

Why?

They acted as they were supposed to, having rebuilt their reserves as the orthodox textbook requires through their bond sales of the past two years. The more reserves you have, the textbook says, the more insurance you have gained against just this sort of dire situation. Or maybe not.

Argentina doesn’t mean anything, they say. It’s just the same ol’, same ol’. These are idiosyncratic problems unique to this one country. The place is always a mess, and when it’s not that just means a temporary reprieve before the next storm hits (still, just two years from door wide open to bailout?) Which so happens to be now.

But things are a little more difficult next door in Brazil. That place is on the brink of perhaps some truly nasty stuff, much of which sounds quite similar to Argentina’s plight (lots of reserves but a currency crisis anyway). That, too, we are led to believe is just Brazil being Brazil. Maybe its just something in the water in the southern portions of South America?

Then you get to other places around the world and again they are struggling monetarily. Turkey. Indonesia. Names you might expect to be on some sort of watchlist. India?

You might then start to get the impression that all these places have something in common, a malady that can’t just be dismissed as isolated circumstances. That’s why Urjit Patel’s writing in the Financial Times this past Sunday was so profound. Finally, one of them on the inside, the head of a major central bank, is stating very clearly that the world has a dollar problem.

While that is all very good, and I really mean that, we are then asked to believe that this one, as opposed to the three others before, is because of this:

Well, that plus this:

Sorry, it just doesn’t fly. I can easily understand why their orthodox eyes are cast suspiciously in the Fed’s direction. That’s all they know. The complete nature of the eurodollar system is quite literally a foreign concept in every sense of the term. They know better than Federal Reserve officials the outlines of the global dollar system, but that doesn’t necessarily mean they have any idea dollars versus “dollars.”

It is very easy to think, well, the FOMC is tightening therefore things are tight. But even that suggests why this line of thinking is so misplaced.

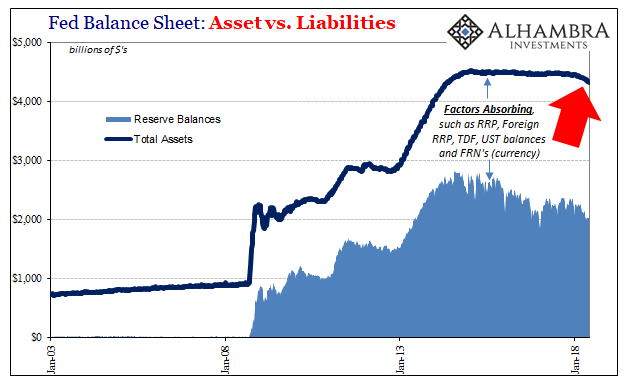

US monetary officials are indeed altering their policy stance in two dimensions. They are raising the federal funds rate at the same time they are deliberately shrinking the overall size of the central bank’s balance sheet. Why are they doing this?

Quite simply, the FOMC believes the US economy is doing well to quite well, and is as likely to be doing better in the future as any other condition. They are by action confirming the American portion of “globally synchronized growth.”

If that narrative is valid, however, inside the US as well as outside, then it still might be reasonable for a place like Argentina to get into trouble despite rising global economic fortunes. But everyone else at the same time, too?

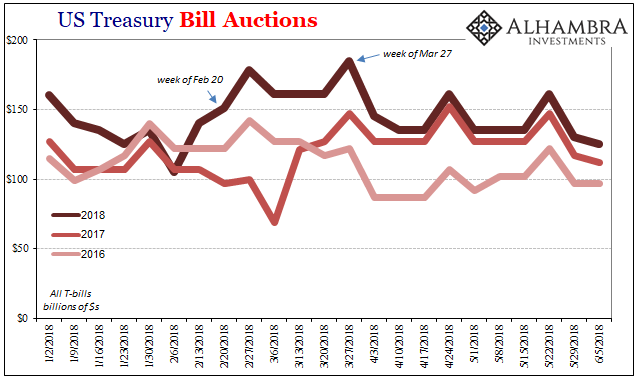

A healthy global economy would propose to the banking system a palpable air of risk-taking. Growth is opportunity in financial and money dealing behavior as part of the necessary components to economy. The safety of UST’s even at slightly higher nominal rates, pales in comparison to what might be let across the whole world if it is finally rebounding from its decade-long slumber.

None of those things are happening. Indeed, in many places the opposite. Quite the opposite.

The focus on the Fed’s balance sheet is little more than the mainstream trying to make sense of what’s really happening but doing so still anchored to the hugely incomplete vantage point of the traditional, orthodox textbook. That goes for other central bankers, too.

It’s an improvement, at least, from 2014-16 where most of the mainstream labored very hard to ignore the worldwide “dollar” retreat, or at most attempted to recast the monetary reduction as a good thing (King Dollar means the US economy is going to soar!) There’s still a lot of that going on today, but more and more we are being confronted with not just dollar funding misbehavior but its offshore center(s).

Since the Fed is projecting tightening, unlike the “rising dollar” period or 2011, it’s now OK to admit rather than disguise clear tightening. For the first time in the crisis era, monetary policy intent and longstanding “dollar” reality are finally aligned rather than lined up against each other. But correlation so doesn’t mean causation.

Stay In Touch