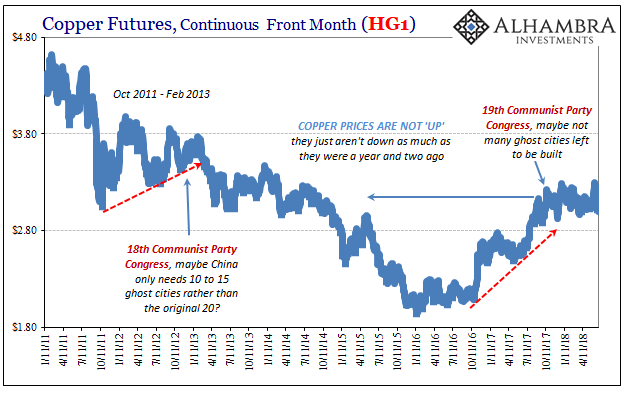

It’s been a wild month for copper. June began normal enough for the metal, with the front month futures price (HG1) still ~$3.05 where it had traded since early March. Then, out of nowhere, the price surged. Starting June 4, in a matter of days HG1 was just less than $3.30. It was the highest price of the year and very close to a multi-year high.

Inflation hysteria was briefly embraced, though never reaching the same levels of enthusiasm as something like this move would have triggered a few months ago. Apparently, all the fuss was about BHP’s labor problems at its Escondida mine in Chile. Rumors of prolonged unrest maybe even a strike temporarily took hold of Dr. Copper, the potential for significant interruption in supply.

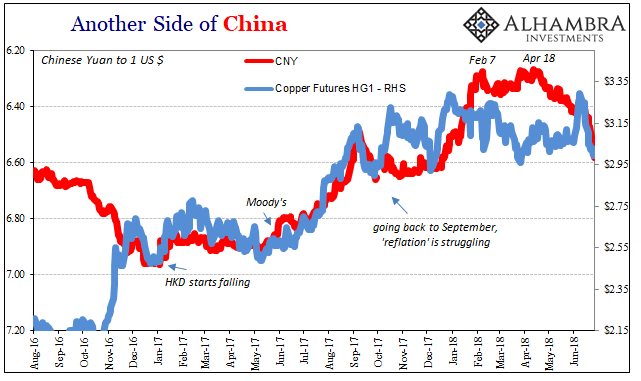

Then, just as quickly, the price surge reversed. Today, copper is lower than when it began the month having sunk underneath $3.00 again for the first time since March 28. If there were Chilean supply problems supporting it on the way up, there are Chinese issues pulling it back down again.

Copper’s price is linked to Chinese factors more than those of any other place on Earth. That makes intuitive sense since China is the place where more stuff gets built. And it’s not strictly an economic relationship, either, for copper is collateral especially in and around Hong Kong ports of entry.

As you can see above, the last HG1 spike wasn’t all that unusual. It hadn’t happened for several months, but since the big move up in September there had been a couple reaching similar proportions. Each time the jump was beaten back. As copper might represent reflation, it’s been tough going for nine months now.

Even as inflation hysteria gripped many places around the world and many markets within them, Dr. Copper has withheld its approval. Like other base commodities, investors were betting on this one metal in 2016 and 2017 as if “globally synchronized growth” might mean something (this time). Unlike some others, however, parts of the copper market seem to have grasped the big message delivered from China in October:

Some are still betting occasionally on an inflation and growth breakout, the happy scenario everyone wants and expects, but since last September there has been a renewed balance of those worrying it’s not any different this time.

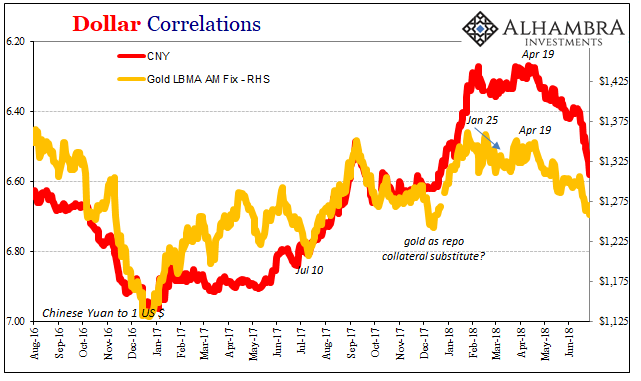

It’s not just copper, of course. A similar sideways trend has developed in gold, too. Another former reflation standout, unlike copper gold has been less buoyant exhibiting more forceful uncertainty of late.

The fact that gold has been almost steadily lower since around April 19 cannot be ignored. It’s the same dates for transition from EM currency concern to burgeoning EM currency crisis.

A lot of gold’s participation in something like that has historically been tied to collateral. Gold is a global collateral that serves as an emergency substitute of sorts. It is one part of the modern system in which the negative funding pressures via collateral develop into the traditional views on sagging gold prices – deflation.

NOTE: For a detailed discussion on the how’s and why’s of gold as collateral, you can go here for an appearance I made on MacroVoices in March. As usual, their terrific host Erik Townsend was careful to make me explain each part of the process rather than just allow my usual style of glossing over details. It isn’t required for what follows here, but it may help answer any questions that surely linger.

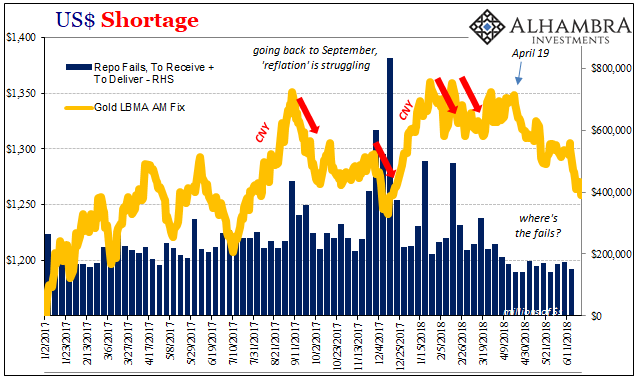

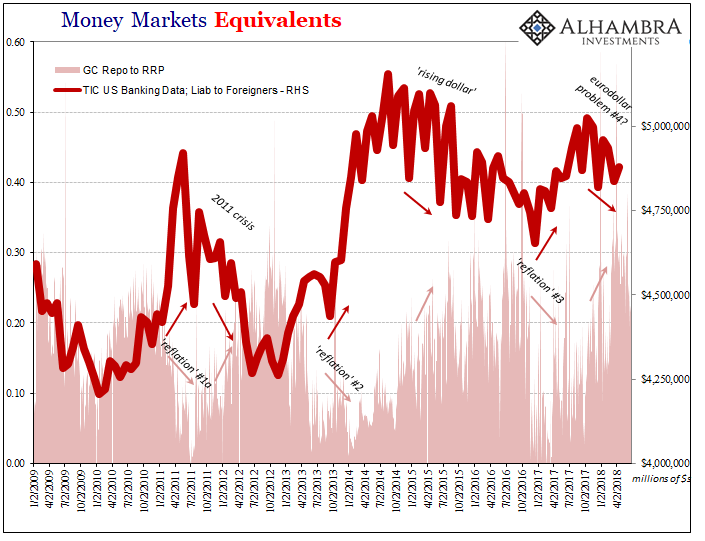

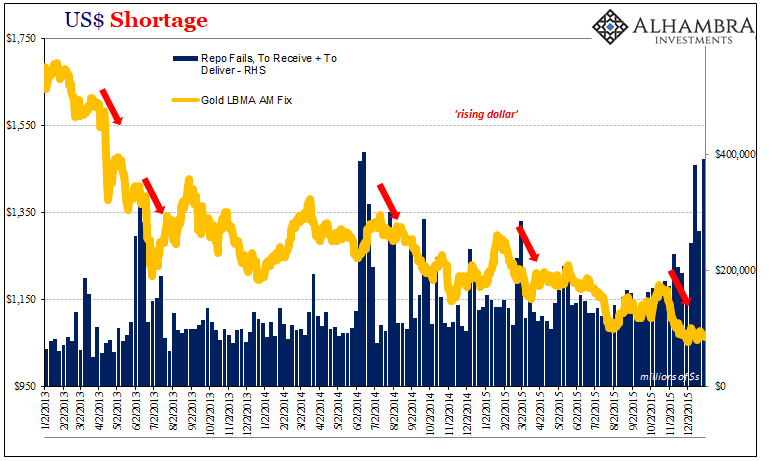

As you can see above, however, there isn’t an indication of collateral problems this time around. Despite all the deflationary impressions left across the eurodollar world, including, as noted yesterday, in repo rates and federal funds of all things, repo collateral hasn’t been too much of an issue. It may seem a glaring omission, demanding some kind of answer especially in the context of where things may be heading.

The repo market is not the only place where collateral is common practice in size. Many types of derivatives transactions are secured by the same kinds of collateral as in repo. Depending upon the type of security or contract, including in the FX space, counterparties are sometimes required to post collateral upfront and then collateral is exchanged as the security/contract is marked to market throughout its life.

As such, you might imagine a case, or several cases, where “unexpected” market movements could create a sizable collateral call. In more severe instances, it could even be where you were on the receiving end of collateral postings (a positive market value which required your counterparty to post mostly UST’s) but the market then moves so far and fast against your position that not only do you have to return collateral already posted to you, you now have to post collateral to that counterparty.

This isn’t as ridiculous as it may sound, even in the practices of market and money dealers. The textbook says that dealers in particular run matched book operations, therefore reducing the risk of large negative imbalances arising, but reality is often (always) very different.

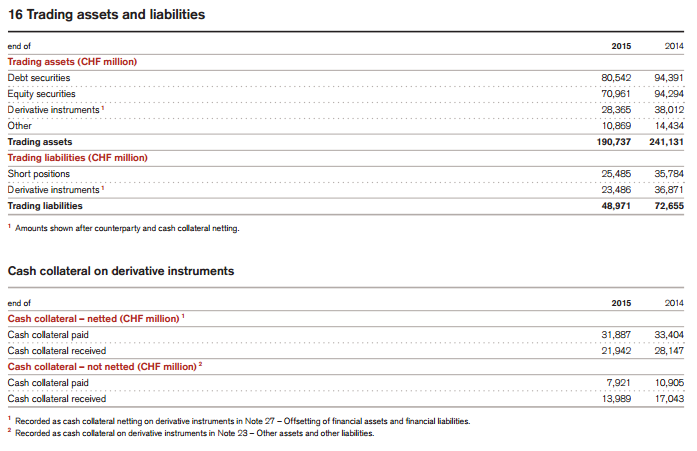

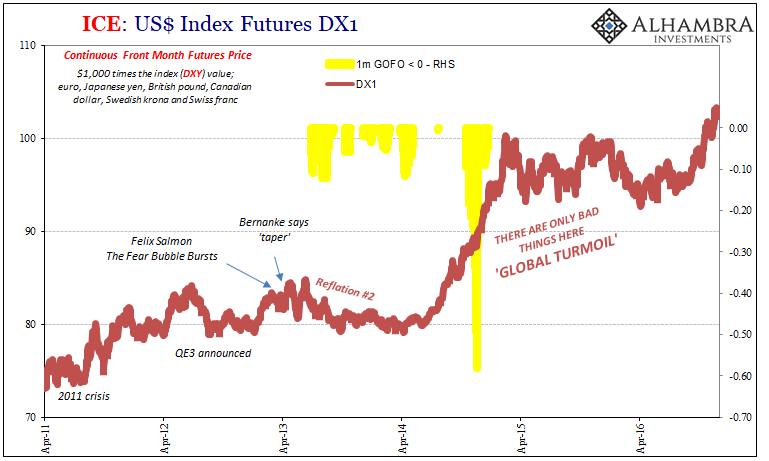

I wrote before about one specific example, Credit Suisse, and that particular bank’s experience during 2015 – the worst of the “rising dollar.”

In 2014, CS received CHF 45.2 billion in collateral (both netted and not) against collateral paid of CHF 44.3 billion. The events of 2015 shifted that position to CHF 35.9 billion in collateral received against CHF 39.8 in collateral paid.

The difference, essentially a CHF 5 billion collateral call, was in contrast to prior years where reported derivatives collateral was more balanced and even. In 2013, the bank reported CHF 32.23 billion in collateral paid against CHF 32.16 billion in collateral received. So while CHF 5 billion does not seem a monstrous burden to a bank (though seriously shrinking) with total assets of CHF 821 billion, it is a significant change with regard to that method of funding since additional collateral paid out to counterparties typically becomes encumbered. On its liability side, CS shows only CHF 46.6 billion in central bank “funds” purchased and repo, meaning a CHF 5 billion drain in potential collateral is a relative hardship, stamping further urgency beyond just further risk in the derivatives book.

Credit Suisse throughout 2015 was shrinking – fast. It seemed as if there was some great urgency behind the bank’s exit primarily from its FICC global eurodollar practices. We can’t know for sure, but we can reasonably speculate that this collateral difference, and any funding difficulties that may have arisen relating to it, were a big part of that decision (liquidity risk).

But how could we know, or at least develop realistic and practical suspicion, that Credit Suisse’s problems were endemic?

It requires a broad survey of “dollar” related activities, gold being one important item in that investigation. Even if repo fails don’t specifically tie to gold price smackdowns across an entire focus period, we can still presume FX collateral through other means.

This was one of the major themes of my appearance on that specific MacroVoices episode. We can infer from gold (and related data) broader collateral conditions than those that only apply specifically to US$ repo (fails).

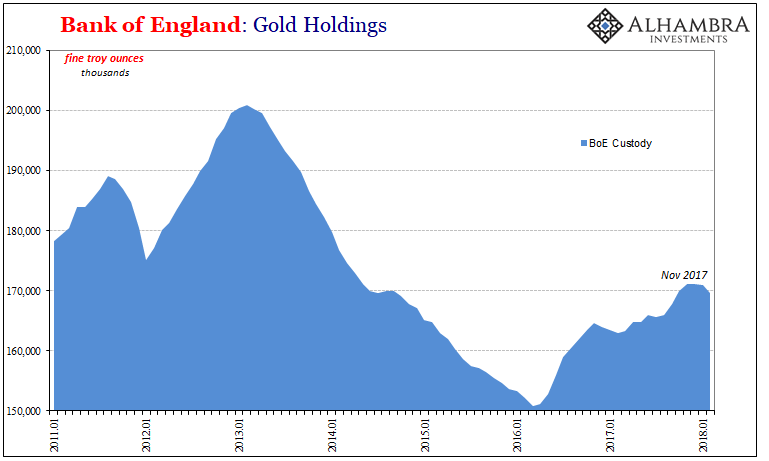

In 2011, the Bank of England began reporting the physical stock of gold it holds in its custody. London remains the world’s premiere gold market and the BoE a long history of being near the center of it.

It is important to understand that the BoE’s reported holdings are not all its own. Nor are they exclusively physical metal on behalf of other central banks. Commercial banks from around the world also store theirs in amongst bullion belonging to those others.

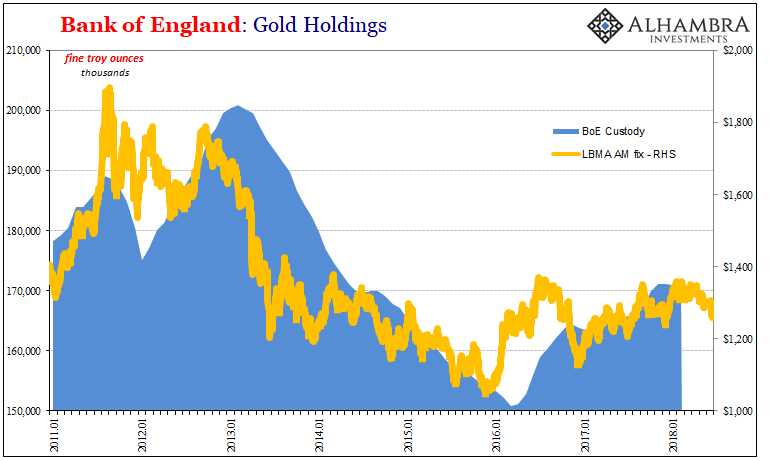

What you might notice just from BoE’s reports is the general outline of gold price behavior especially since the big drop in 2013. There is pretty good direct relationship between gold in BoE’s possession and in which direction (with a lag), and how far, gold prices might go.

If gold is disappearing from the BoE’s reported holdings, we can infer that the metal is being used for collateral substitutions along the lines as I described them to Erik Townsend (and pictured them in the chartbook accompanying the interview). It works out as deflationary in funding and liquidity as well as gold’s price.

The opposite has held true, too, meaning that as gold in 2016 suddenly flowed back into BoE custody the price has generally risen along with it – reflation.

Since November 2017, BoE holdings have declined again. It’s not yet a substantial amount, but after several months it more and more represents a possible trend change. Factoring a lag to September, it corresponds to gold’s (and copper’s) price struggles.

Unfortunately, the data is published several months in arrears, meaning that the report for February 2018 is the latest figure on hand.

Since repo fails were still happening at that point, we are left making a bit of a leap about what may be going on April 18 forward as repo fails fade out of the illiquidity/collateral/gold picture. Thus, we are left waiting for the BoE to confirm in the months ahead what we suspect about the months already behind as well as anything else that might develop in between – including gold prices registering a new multi-month low today.

It would at least be consistent with prior experience, especially in the year or so leading up to the “rising dollar” and then the main part of it in later 2014.

In other words, it was a lot repo but not all repo weighing on collateral, thus gold, and helping push the “dollar” up to globally devastating effect. There were very likely collateral severe strains out there in FX, too, and not just on Credit Suisse, that for whatever reasons (including limited CIP) didn’t affect the repo market the same way every time.

To sum up: what I suspect has happened since April 18 is that FX has been more exclusively the epicenter of growing “dollar” problems that in all likelihood, in my view, are similar to Credit Suisse’s 2015 experience. Any background relationship to China is relatively self-evident for expectations (risk) as well as in direct practice (Hong Kong).

Therefore, as the BoE publishes its gold custody holdings over the coming months I expect that they will, factoring some lag, show more significant declines past April. That would confirm collateral and gold as a substantial factor in what has taken place so far.

This isn’t to say the repo market is out of the picture entirely; quite the contrary, as noted above and yesterday. Rather, in terms of collateral flow there hasn’t been as much effect in that part of the global “dollar” apparatus (which could be, ironically, the work of additional T-bill supply which is entirely OTR and therefore helpful only in that market).

Where all this fits in on a big picture level is to further confirm what is merely being hinted at by these metals and how these metals are being used, or not used. An end to Reflation #3 and the arrival of the first stages of what would almost surely follow. The possible switch from a general inflationary trend back again toward deflation all over.

Eurodollar Event #4. It’s not gonna show up tomorrow since these things are, obviously, very complicated and drawn out processes, so we’ll have time to come up with a better name – if that’s what’s happening.

Stay In Touch