Banks in China have to hoard liquidity ahead of their weeklong holidays, twice each year. The bigger of the two, related to the Chinese New Year, occurs in either January or February. The second, associated with China’s National Day, takes place at the beginning of every October and is still a formidable challenge to the monetary system. Depositories build up their cushions so as to be prepared for when the Chinese people hold extra currency, or lower deposit balances, knowing that for an entire week the banking system will be closed and therefore unable to process transactions.

To try and accommodate the imposition, the People’s Bank of China, the country’s central bank, will increase its monetary base stockpile in advance. Relying on statistical forecasts, central bankers attempt to predict the nation’s gargantuan cash need which can run into additional trillions. The goal is to increase systemic liquidity beforehand such that local illiquidity as a normal part of the holiday schedule doesn’t become anything more than the usual nuisance.

For China’s National Holiday, that means accommodation falls in September. And for the banking system in the same month, rising illiquidity if the PBOC isn’t nimble.

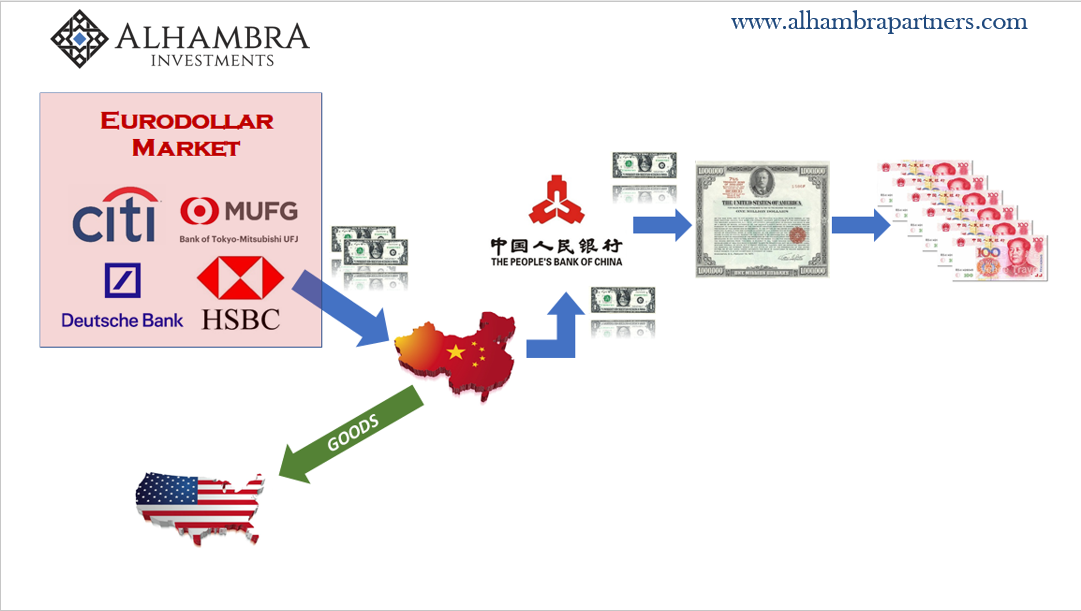

This year’s challenge was as difficult for officials as it was three years ago. To support CNY, to keep the currency exchange from falling further, authorities used more foreign “reserves” than they had been throughout the year. This simply means to supply “dollars” into the local Chinese system that requires them for everyday economic necessity.

If the eurodollar market isn’t being supportive, the PBOC either has to step in and subsidize or directly supply the marginal dollar requirement (“short”), or let banks fend for themselves (huge CNY negative; the price Chinese banks “short” dollars must pay to keep them flowing).

But if the PBOC opts for some flavor of “dollar” rescue it constrains itself for its own purposes – including systemic liquidity surrounding the Golden Weeks. The connection between the eurodollar system and domestic RMB money supply is discussed in more detail here.

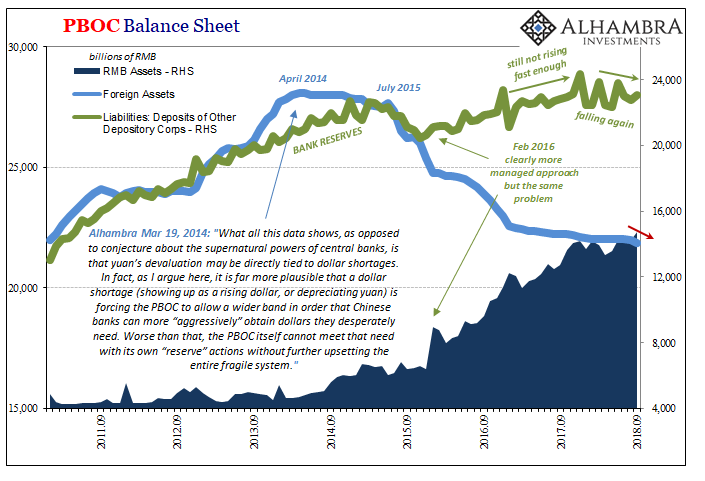

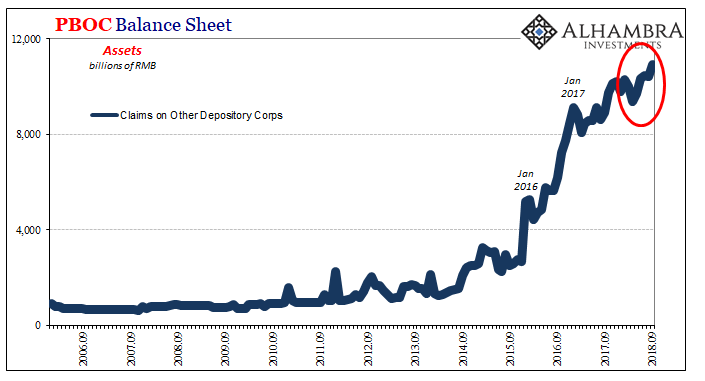

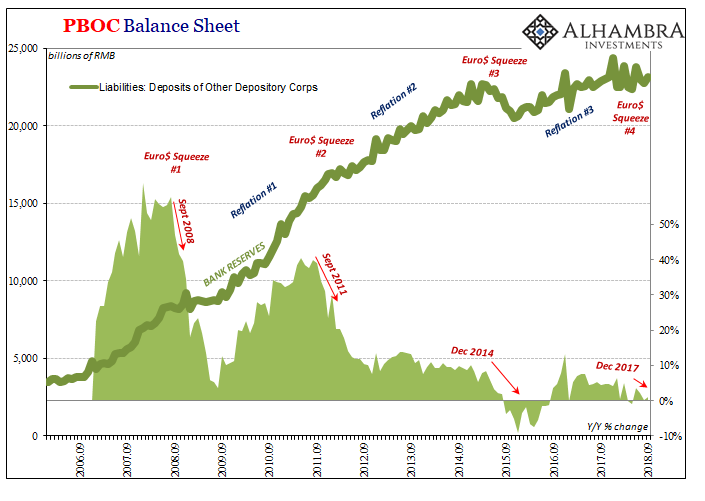

With foreign reserves falling at an accelerated rate in September, in order to offer even a minimal increase in base money required the PBOC to appeal once again to other RMB liquidity measures. These are shown on the asset side of the balance sheet under “Claims on Other Depository Corporations.” The MLF falls into this line.

In the month of September, RMB window usage increased by just less than half a trillion. And yet, given that large addition in assets the PBOC’s liability side, the money side, managed only a small expansion.

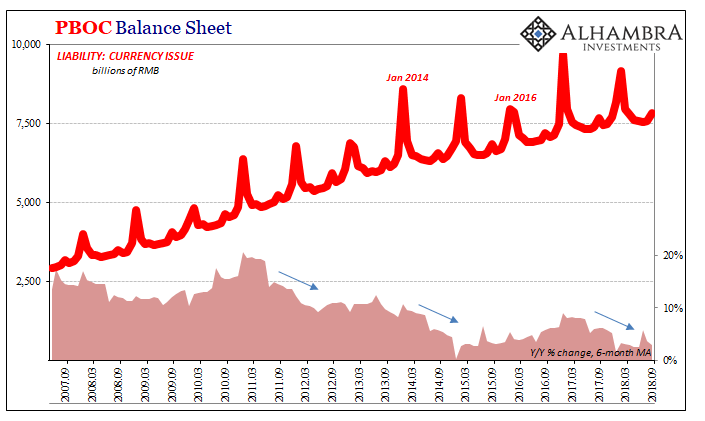

The two main elements on the liability side are physical currency issued and bank reserves (“Deposits of Other Depository Corporations”). As to the former, physical currency at issue increased by just 1.9% in September 2018 over September 2017. That’s the smallest gain (not counting year-over-year changes skewed in January or February by New Year’s calendar base effects) in modern Chinese history.

By comparison, in September last year, currency outstanding rose 6.5% above the previous year. In troubled September 2015, the central bank managed to move physical currency ahead by 4.4%.

The other form of RMB money is bank reserves. It is this part of the liability side where the PBOC is attempting to use flexibility and discretion. Having obtained massive amounts of RMB reserves years ago when eurodollar markets were extremely kind to China, the banking system has those locked up reserves available for use whenever the central bank gives the go ahead.

This year, like 2015, the PBOC has done just that. The reason is quite simple, because the central bank cannot increase systemic reserves while the country is being squeezed by the eurodollar markets. It is hoping that by allowing banks to use more of what they already have that will offset reduced growth in them, or even another contraction.

Bank reserves gained just 1.1% in September, after rising by just 0.3% in August. The 6-month average rate is down to 1.0%. That’s the slowest average growth since 2016.

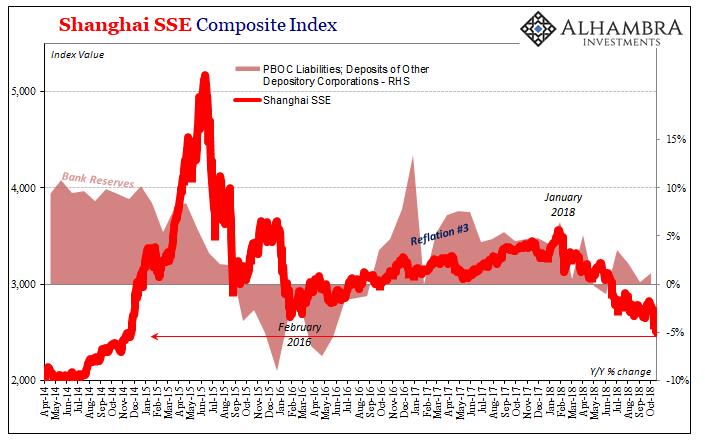

Therefore, in a month when systemic liquidity really counts China’s central bank managed only minimal contributions to either form of RMB money. It wasn’t a catastrophe, obviously, but it wasn’t exactly smooth, either (check out Hong Kong). Chinese markets reopened from the holiday in the second week in October in full-blown liquidation.

The PBOC’s balance sheet figures merely confirm what we have suspected all year. The last RRR cut earlier this month was indeed a warning of these imposed external eurodollar constraints – that they would continue and that the PBOC is trying to get the private banking system to pick up some of the slack.

It hasn’t been working. Not only did the stock market drop but money rates in China are at best stable, indeed they may be rising despite the reduction. SHIBOR rates were down only a small amount to begin last week and then rose slightly the rest of it. Today the overnight rate (unsecured interbank lending of RMB) was 2.475%, above the rate from Friday, October 12, the last session before RRR.

This isn’t a surprise, really, given how everything transpired the last time (2015 and 2016). Instead it only shows, quite clearly, just how few options the central bank has left. It takes the idea of a neutral monetary policy to an extreme; trying to keep things stable shouldn’t be a white-knuckle ride for any monetary institution let alone a major one like the PBOC.

This is especially true given Western perceptions of this one central bank. As much as Economists and the media defer to the Federal Reserve and its officials, to China’s central bank there is almost a worshipful expectation for omniscience. Some of it is the establishment’s love affair with the idea of a technocracy; full authority and power given to the best and brightest so as to come up with “optimal outcomes” on behalf of the world’s common folk.

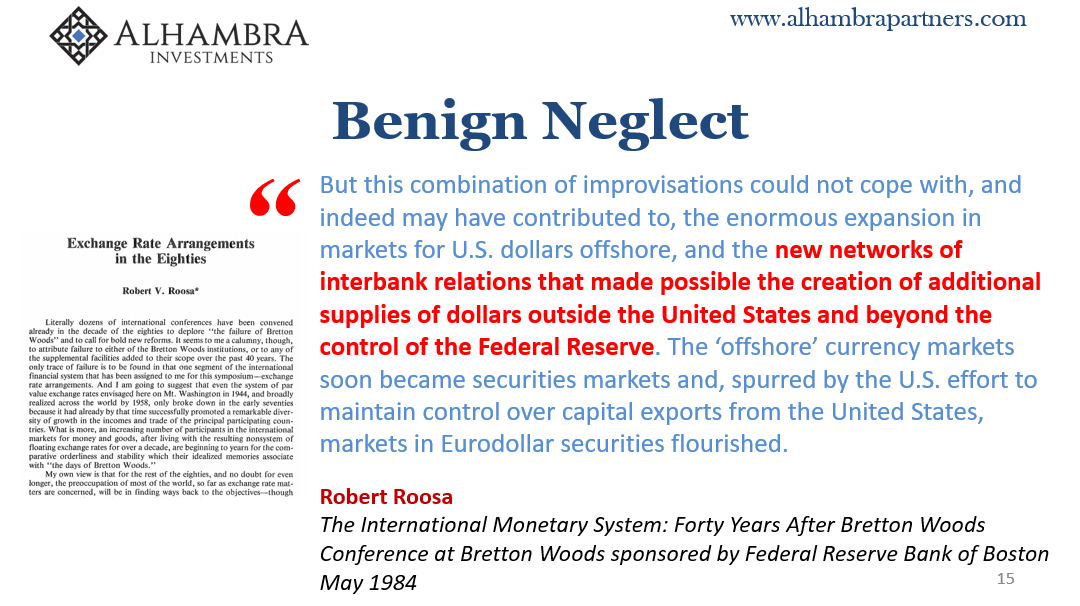

What the last half decade has proven, as if 2008 wasn’t enough, is that when it comes to technocracy particularly in this format there just is no such thing. For there to be technocracy, there has to first be technical competence. China’s central bank is simply no match for what it doesn’t fully understand, the eurodollar system.

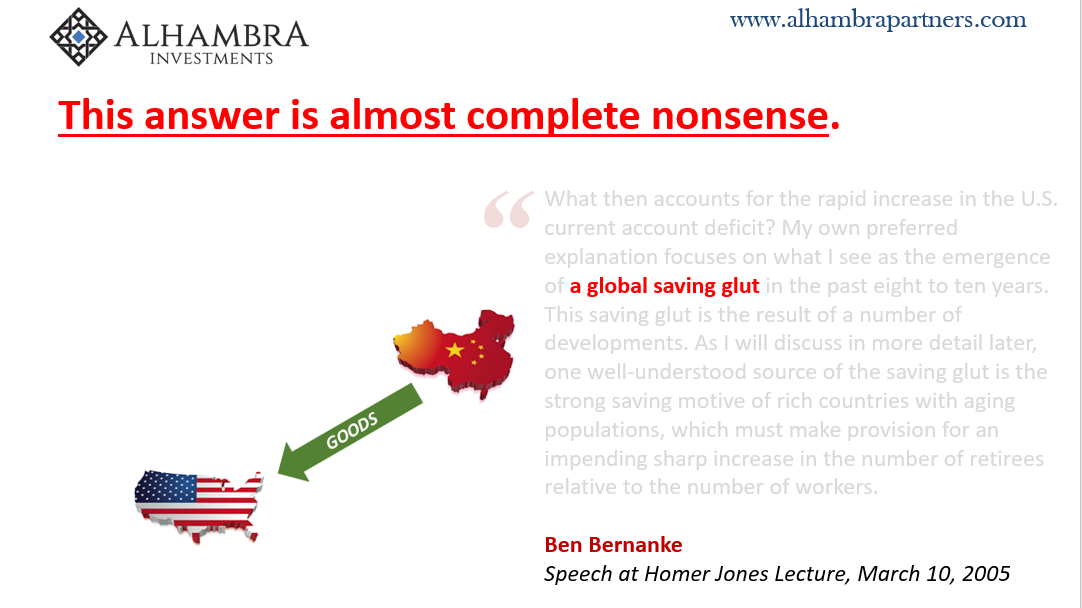

It is therefore a little tiny bit ahead of its Western counterparts; at least Chinese central bankers know it is there, compared to the determined ignorance that dominates the Federal Reserve and the others like it where for decades now they would prefer not to even contemplate the possibility (Bernanke’s preposterous excuse of a “global savings glut”).

For Chinese base money to fall to essentially nothing, to have the PBOC almost literally stop the literal printing press, in the period just before a Golden Week no less, this is no small thing. Working backward we arrive at the stark conclusion that there is no global economic acceleration, synchronized or not, and not even global growth. If there was, China wouldn’t be in this mess. Global money mess.

Stay In Touch