What a difference a year makes. As 2017 finished up, the Federal Reserve was widely seen as turning “hawkish.” Inflation in the US, many believed, was about to be unleashed by a blistering labor market so tight we’ve not seen anything like it in decades. The central bank would be forced into a quickened pace of “rate hikes” attempting to head off the inflation monster before the economy became too good.

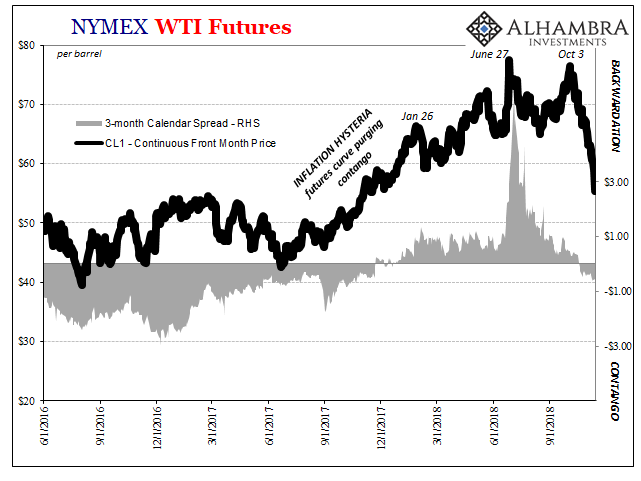

As it has turned out, there were no extra rate hikes in 2018. If anything, there was a confounding technical adjustment instead. The unemployment rate has remained low enough, but inflation has been a product purely of crude oil prices. And not even high WTI, rather still an uptrend coming off the last low. There was a lot about 2017’s Reflation #3 that struck awfully hollow.

The exuberantly hawkish Fed has slowly morphed into something completely different right before our eyes. Whereas at the end of 2017 “they” forecast perhaps five or even six increases in the federal funds corridor, approaching the end of 2018 “they” now wonder if there might only be three or perhaps two in 2019. Something has changed.

Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell and his colleagues are likely to turn more wary about marching interest rates higher after delivering a widely anticipated quarter percentage-point increase in December.

Prospects for slowing global economic growth, fading U.S. fiscal stimulus and volatile financial markets all argue for more caution once officials lift rates next month near or into neutral territory, where policy neither spurs nor reins in economic activity.

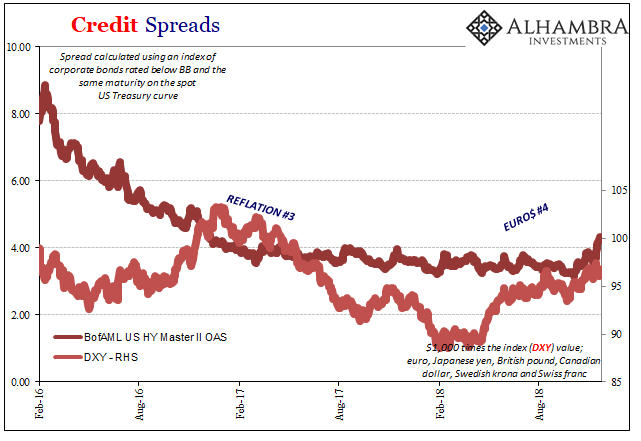

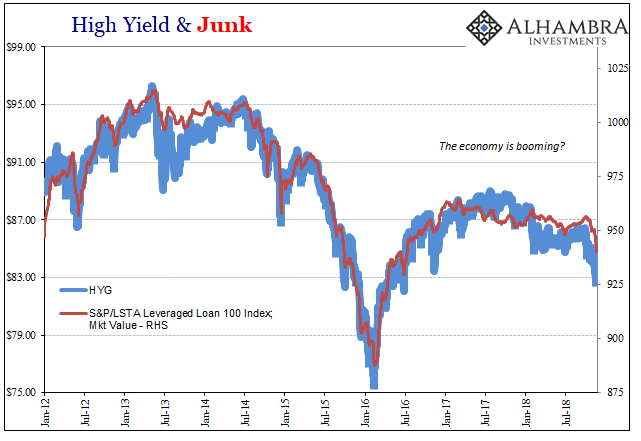

Not quite the booming economy if there are too many “headwinds.” Everyone had been expecting all that dollar stuff in the first few months of the year would fade. They claimed T-bills, Korean war, trade war, and a host of other explanations that were supposed to amount to “transitory” disturbances of no official import. Powell had his unemployment rate rated ahead of everything else.

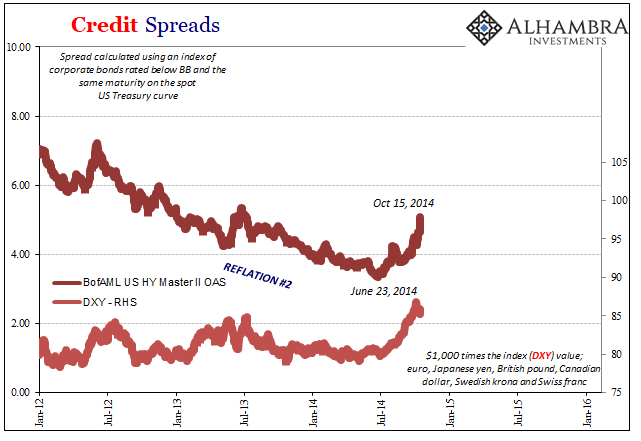

Instead, “volatile financial markets” which most people interpret via the Dow Jones Industrial Average has been in much more relevant and meaningful places an understatement. The dollar rises and nothing good comes from it.

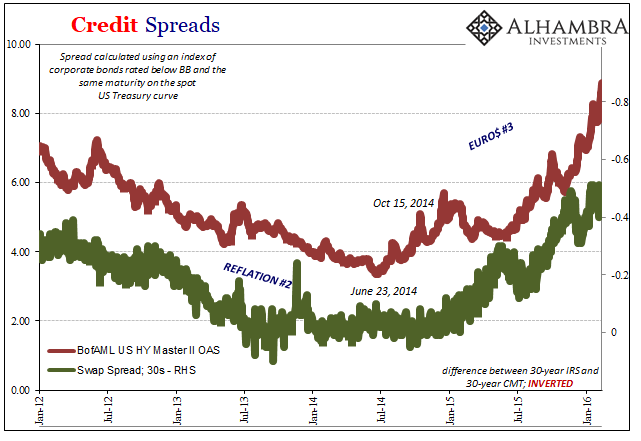

We’ve seen this all before, nearly an identical match to the latter half of 2014. History never repeats exactly but boy does it often rhyme with perfect pitch and tempo. Between June and October of that year, all the same things said about the current economy were said then, too. It was the “best jobs market in decades” and the US economy was experiencing the best two quarters (in terms of GDP) in a very long time.

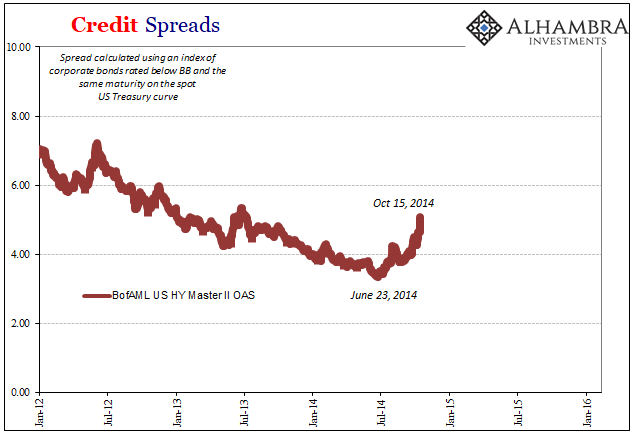

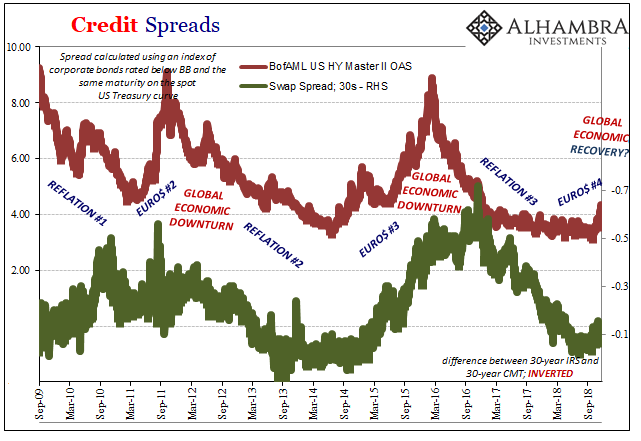

Yet, during those same crucial months warning signs proliferated and escalated. One key factor was credit spreads. When we talk of the bond market we often mean US Treasuries or other similar “safe assets.” There is more to the market than that, of course, including several classes of risky and very risky components. The difference between these classes, the credit spread, can tell us a lot about what the market, the whole bond market, perceives as to risk as well as opportunity.

Falling for several years, credit spreads in June 2014 suddenly spiked. By itself, it was already an important contraindication for the Fed as it was ending its third and fourth QE programs having diagnosed a full economic recovery off the Establishment Survey and GDP. Taken with other measures, the rebuke to the common narrative was compelling and harsh.

Yet, it was widely ignored because people have been given this sense that economic growth is a given. That when it is absent for any significant length of time it is only a matter of time before it comes right back. By the second half of 2014 it had been already five years of depressed “recovery.” Never mind the widening monetary distress, they said, everything could only be good; maybe too good.

It was too easy through nothing but emotion to set aside some really concerning changes in market behavior. Something was very different in those several months of 2014 even if the US economy as in others around the world there seemed to be strength in a lot of accounts. Current indications are simply no match for these forward looking.

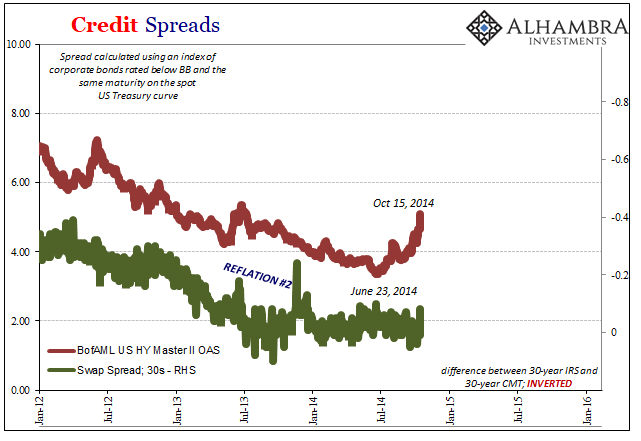

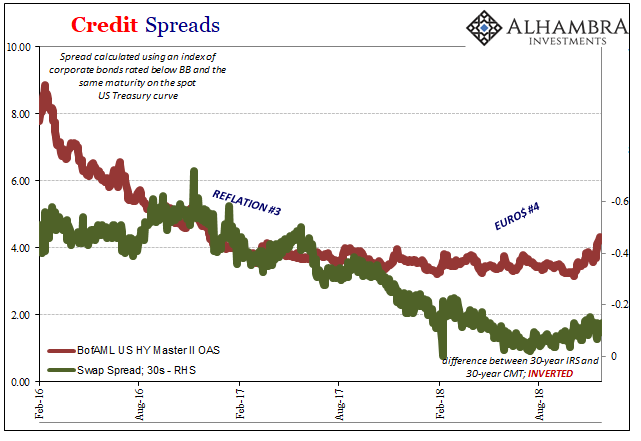

You can always talk yourself out of honest analysis piece by piece as was done in the mainstream. Swap spreads were technical factors, many claimed, a result of the end of QE3 (MBS buying). The dollar was rising because the US was the cleanest dirty shirt. And credit spreads were up because they were way too narrow for many years.

Except, taken together along with any number of other market signals these were pretty straightforward leading into yet another downturn.

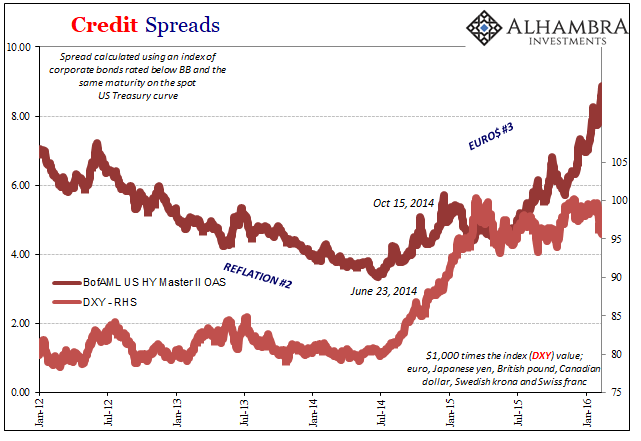

This was just four years ago, but it’s as if it never happened that way. History rhymes so closely because no one was paying attention the first time, or, as fate would have it, the first three times. Now comes this fourth, an impending shift in the global economy that even the Federal Reserve can see.

And time does have a lot to do with it. If people and policymakers were impatient in 2014 after five years of lackluster “recovery”, then three years further on the rashness bordered enough on hysteria. They couldn’t possibly miss in 2018; it had to happen this time.

Why now the more “dovish” narrative?

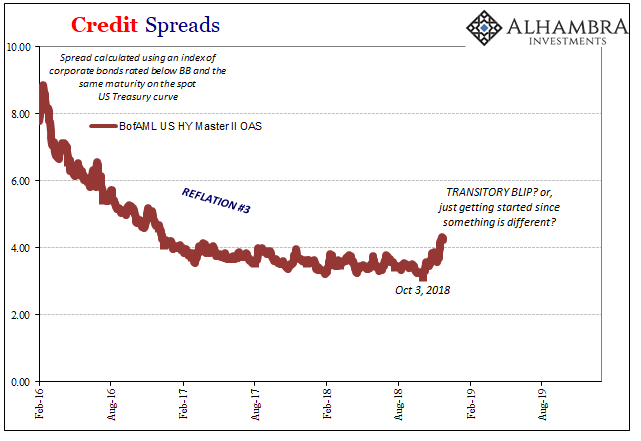

A lot of things have changed over the past two months. For the first time in several years credit spreads are rising. It’s not a big change, but it needn’t be. Like those specific months in 2014, what is indicated by spreads since October 3, 2018, is a potential shift in trend.

And we can talk ourselves out of it in isolation if we wish. We could even use the same reasoning, especially how spreads have been even narrower for longer during Reflation #3 than during Reflation #2. But it’s not just uneasiness in credit alone.

Things are different, except they are the same. In other words, the post-2007 cycle is merely being repeated over and over and over (and now over again). The economy neither grows nor recesses, except that by not growing it gets nowhere and therefore contracts in the only terms that matter: non-linear.

The world falls further and further behind with each false dawn because each and every one is a false dawn. Globally synchronized growth, the third hope, has largely disappeared already. The US “decoupling” is now coming apart, tooThe direction is increasingly clear, and not just clear but visible and unambiguous. Again.

Credit spreads are just the latest sign we’ve all turned back in the wrong direction.

Stay In Touch