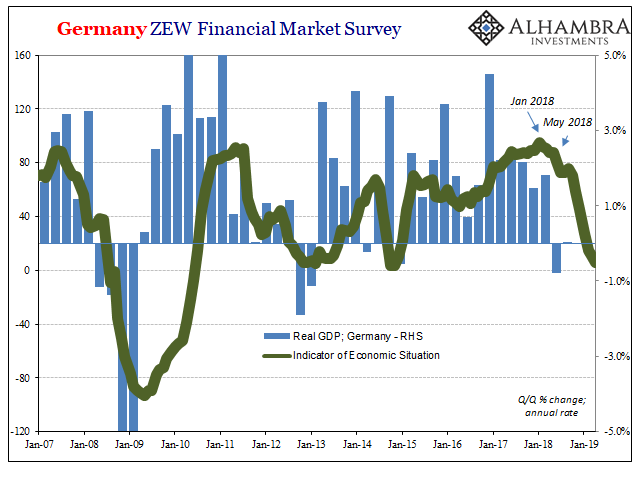

Germany’s ZEW survey became the latest to pick up a pick up in sentiment. This particular appraisal had been one of the first early on last year to suggest a beginning slide toward downturn. In its latest reading for forward expectations, the index registered +3.1 this week. It was both the highest and first positive reading since last March.

Green shoots!

This contrasts with the other part of the ZEW, surveyed responses gauging sentiment about the current situation. This other one fell to just +5.5, the lowest since November 2014 and around the same low level as the last time Germany experienced outright contraction. It continues a summer-time slump that indicates the German economy may be on the doorstep of one already. If Germany, then the rest of the global economy.

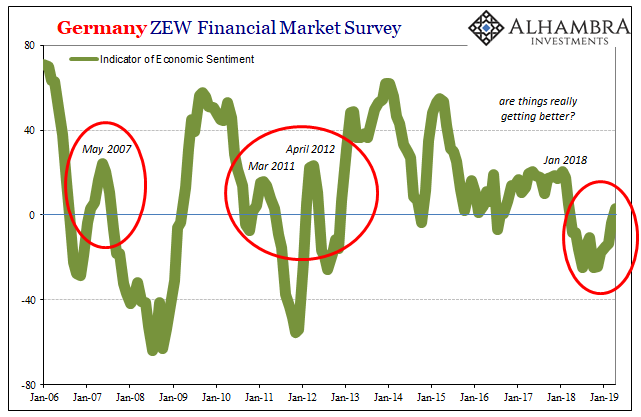

So, which one is it? We are supposed to put the two parts together. For April 2019, this would seem to suggest the European economy is in some trouble but may already be on its way out. The problem with that interpretation, though, is how the future sentiment index has done this sort of thing before. Several times, actually.

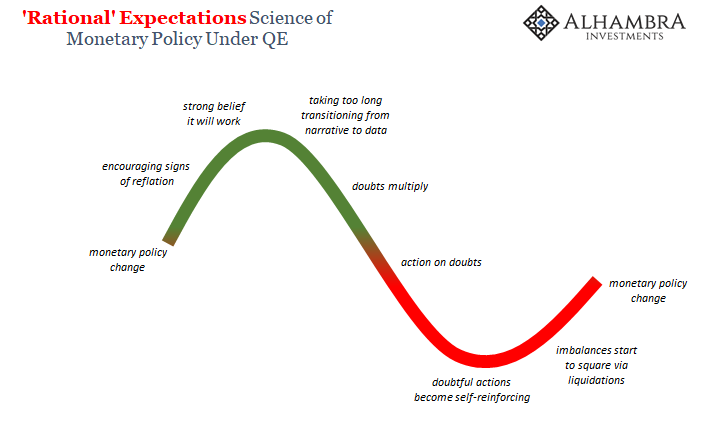

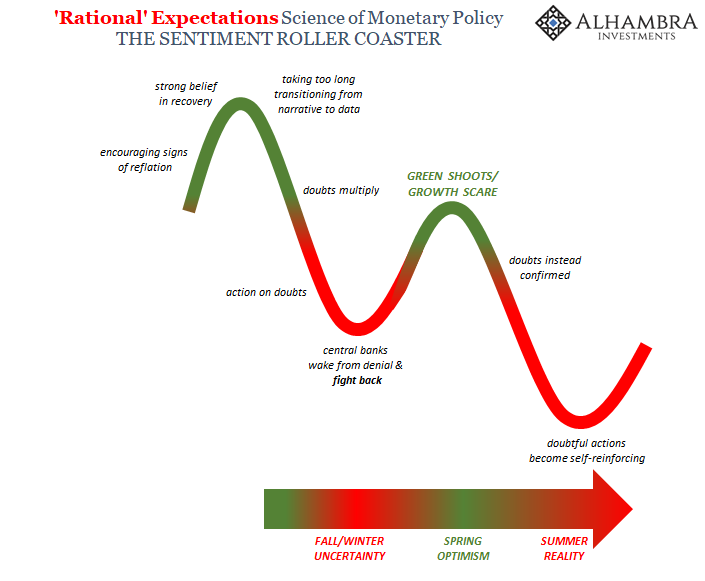

Our model of these eurodollar cycles is somewhat incomplete, too simplistic to fit actual observations especially on the downswing. Overall, this is how they have looked:

Not everything is so black and white; or, in this case, green or red. In fact, the global economic history of the last twelve years suggests more nuance, particularly around the boundary where green has turned red.

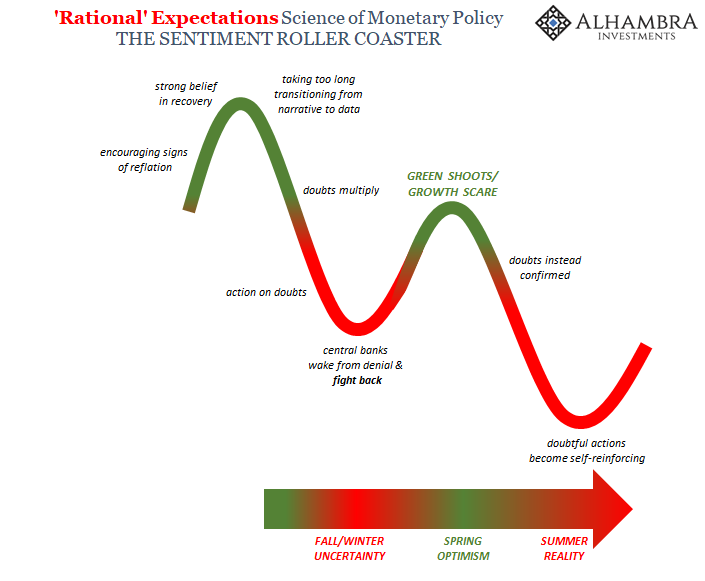

Nothing ever goes in a straight line. This cliché applies to the economy as well as markets. The Great Financial Crisis of 2008 was actually two, and in many ways so was the Great “Recession.” Things got serious in the autumn of 2007 and winter of 2008, then an interlude when things appeared to get better.

A big part of that middle was central bank participation. Back then, officials spent that initial downturn in a lot of denial about its seriousness. Eventually, though, central bankers started to fight back. There were stepped up programs, things that before 2008 we thought we’d never see done. And then in March, they “rescued” Bear Stearns.

Following that, green shoots and cautious optimism. Many people grew more positive because the Fed, in particular, had flexed its muscle at long last. Don’t fight the Fed!

It didn’t last, of course. By summer 2008, the deed was done; long past the point of no return. Springtime optimism quickly faded into scorching hot reality.

It wasn’t just 2008 and Euro$ #1 when this pattern applied. During Euro$ #3 same damn thing. Autumn 2014 and Winter 2015, plenty of uncertainty as well as determined denial. The economy was booming, maybe even overheating officials kept saying.

Then, in the spring of 2015, there was a bit of a turnaround. Things did seem to get a little better, at the very least perhaps a bottom, it wouldn’t get any worse. The PBOC had done some stuff (like peg CNY), the Fed became less hawkish (the first “pause”), and the ECB unleashed its first full-scale QE.

Again, the green shoots appeared until it all fell apart later that summer.

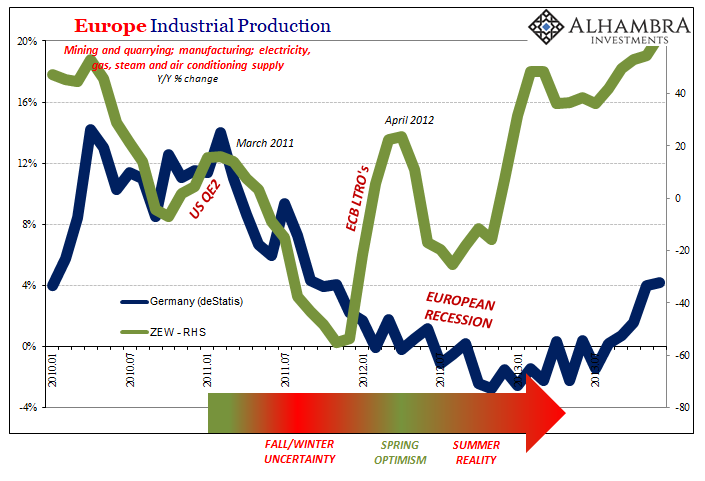

This green shoot roller coaster was even more pronounced for Germany and Europe during Euro$ #2. In the autumn of 2011, it really looked very bleak. Several European banks were rumored to be the successors to Lehman Brothers, and the global economy, which was supposed to be several years into full-blown recovery at that point, had clearly sputtered as a consequence.

Germany’s ZEW, the forward-looking sentiment part, began to sense the downturn early in 2011. By the end of that year, the index was an alarming -55.2. This was 2008 bad.

But then, it turned right around just in time for spring. By April 2012, the ZEW had surged by nearly 80 points, back above zero all the way to +22.3 in a matter of just a few months. It looked like from the ZEW’s perspective Europe would avoid a serious downturn. Whatever had happened, it seemed, it was already over.

Why were German Economists and bankers thinking this way in the first months of 2012? Four letters: LTRO.

At the end of December 2011, the ECB offered the first of its massive (purported) liquidity operations (LTRO1). And then to make sure it stuck, the European central bank conducted a second auction (LTRO2) at the end of February 2012. The “right” people especially in the financial media were thoroughly impressed.

These, of course, didn’t actually work. By July 2012, Mario Draghi was issuing his (in)famous promise to save the euro which wouldn’t have been required if these liquidity operations were as accommodative as advertised.

But that’s largely the point about sentiment. In those first few months of 2012, most if not the overwhelming majority of people including those who participate in these surveys really thought the ECB had undertaken some very big accommodations; if not money printing (most don’t understand what counts as money printing, so anything a central bank does these days is simply written down as that).

As much trouble as the European economy may have run into in late 2011, when Mario Draghi finally broke out of his denial surely this new program (which was going to total nearly €1 trillion) people really thought there was no way it would fail. Central banks, we’re taught, are powerful and competent. Here was the ECB demonstrating its full capabilities.

Instead, by Q4 2012 German GDP was negative and in November that year even the most optimistic LTRO proponent central bankers had admitted the whole of Europe was in recession which would end up lasting a good ways into 2013. So much for that Spring 2012 swing in sentiment.

Sentiment is still keyed on monetary policies. Most, even in 2019, haven’t been paying close enough attention to realize there can’t be any money in monetary policy (if there was, how would there ever have been a 2008 in the first place?) And the media reinforces the message over and over and over. This is all very powerful stimulus, they say. Therefore, when a central bank switches up and grows dovish it can’t be anything other than positive for the economic future.

Only it’s not. You can get away with playing on sentiment but only for a time – and that time, for a lot of reasons, falls around springtime. Optimism, however, doesn’t fix what’s underneath, the reasons for the descending trajectory in the first place.

It’s impossible to know why German Economists and bankers are a bit more positive in April 2019 about the future than they’ve been in a year. Given history, though, I’d wager it is more based on the Fed “pause”, the ECB’s aborted rate liftoff (along with, as a start, the upcoming third T-LTRO), as well as the usual mistranslation from Chinese over the PBOC doing a bunch of stuff nobody really takes a deep look at.

It is Spring 2019 and the central banks have fought back. Right on cue. What are the chances this time it actually makes a difference?

Stay In Touch