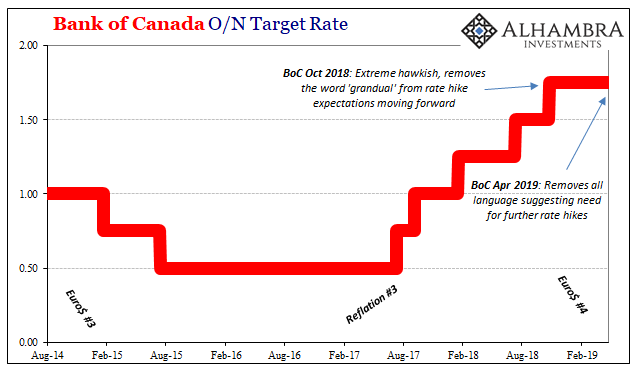

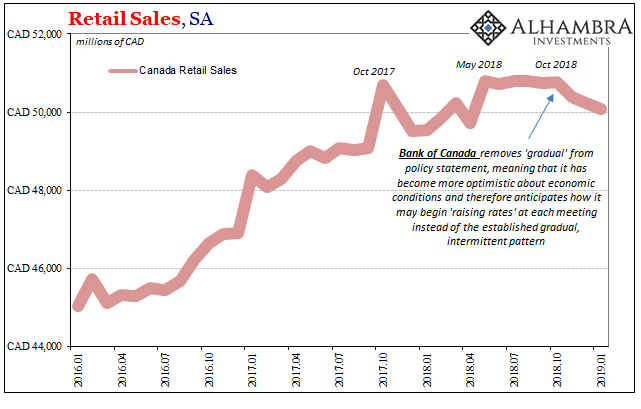

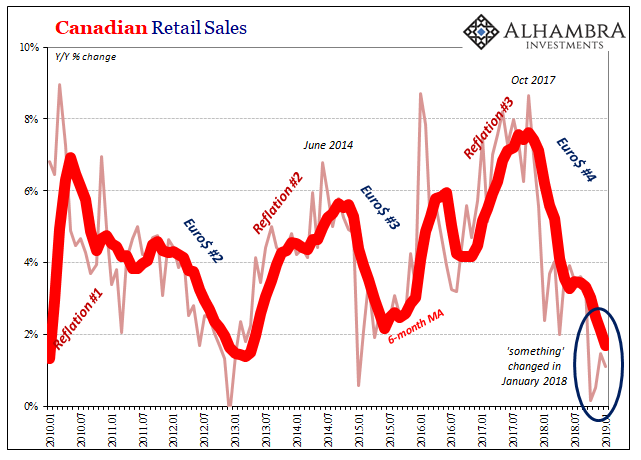

Back in October, late October specifically, the Bank of Canada removed the word “gradual” from its policy statement. Inflation, staff Economists projected, was moving up as was the Canadian economy. It was finally time to become more aggressive. Freed from that one word, BoC officials could opt for a “rate hike” at every meeting.

It was widely expected in December that’s what would happen – the first consecutive benchmark rate increases in the cycle. Canada was leading, way out in front of the inflationary recovery race.

Except, no, the October rate hike was instead in all likelihood the central bank’s last. The policy statement issued today up North looks very, very different. There are more hints of rate cuts than anything like what was being talked about in the final months of 2018.

It needs to be asked again and again; how can officials get it so wrong? Time after time, this is what happens. They project strength leading to obvious acceleration only for the trend to end in the same way as Japan has been selling it for nearly thirty years.

Central bankers keep saying whatever it is that is holding back each economy (they never really get into the details) it is temporary or transitory. Yet, the only thing that’s proved to be so brief are these windows when conditions somewhat passingly resemble how that’s possible.

By October 2018, the economy was already looking dicey in Canada – as everywhere else. The slowdown was obvious by that point, very well entrenched (May 29 unsurprisingly shows up here, too), still the BoC was undeterred. Again, why? The evidence was no longer in their favor, such that any data was genuinely good to begin with.

They really have no idea what they are doing. Any of them.

The Japanese bank Nomura recently made news for announcing more cuts to the institution’s core business. These are actually related to Canada’s struggles. For one, as the bank’s CEO, Koji Nagai, told the Financial Times (thanks M. Simmons) a few days ago, something really changed late last fall. It’s like the whole global system struck a landmine together.

“There is no liquidity any more so the market is dead because of the central bank’s monetary policy,” said Mr Nagai. “The fixed-income market is dead due to the zero interest rate.

“Still, we expected that it would normalise or return modestly at some point. But we began to realise . . . last November or December that it won’t normalise or return for some time.”

Like Canadian monetary authorities, Nomura was very much anticipating normalcy out of 2018; only to see it turn so sour around November and December. Unexpectedly.

Nagai blames the zero interest rate policy of central banks for destroying his “fixed income” or “bond trading” business. But what he is really saying is that it was the lack of recovery which, ironically, the ZIRP policy was supposed to ensure.

That’s why he expected FICC would “normalize or return modestly at some point.” Recovery means higher interest rates, they go hand in hand. In fact, recovery brings only higher interest rates which are welcomed not as “tightening” but as harbingers of monetary and economic success. And with them, more determined business in the bond trading game. The very outcome Nomura was banking on.

So, it isn’t higher rates that killed off the global recovery and with it Canada’s participation. The problem is the very thing Nomura laments, just like Goldman or Société Générale of late: the lack of bond trading success.

In that way, Mr. Nagai contradicts his own story. Higher rates mean greater opportunity, the fixed income business springing back to life. It is, after all, opportunity that drives everything – in consideration of risk. Zero interest rate policies, therefore, don’t create opportunity they very loudly proclaim the lack of it. It is so obvious even central bankers can see it this way (and they are, as BoC proves yet again, the last to figure these things out).

Thus, the Bank of Canada in switching from aggressively “hawkish” to more than probably rate cutters signals, what? It’s not likely the only reason, but perhaps a big one to explain today’s bond market move. Lower rates aren’t stimulus, they are the failure of so much repeated “stimulus.” Japanification.

Stay In Touch