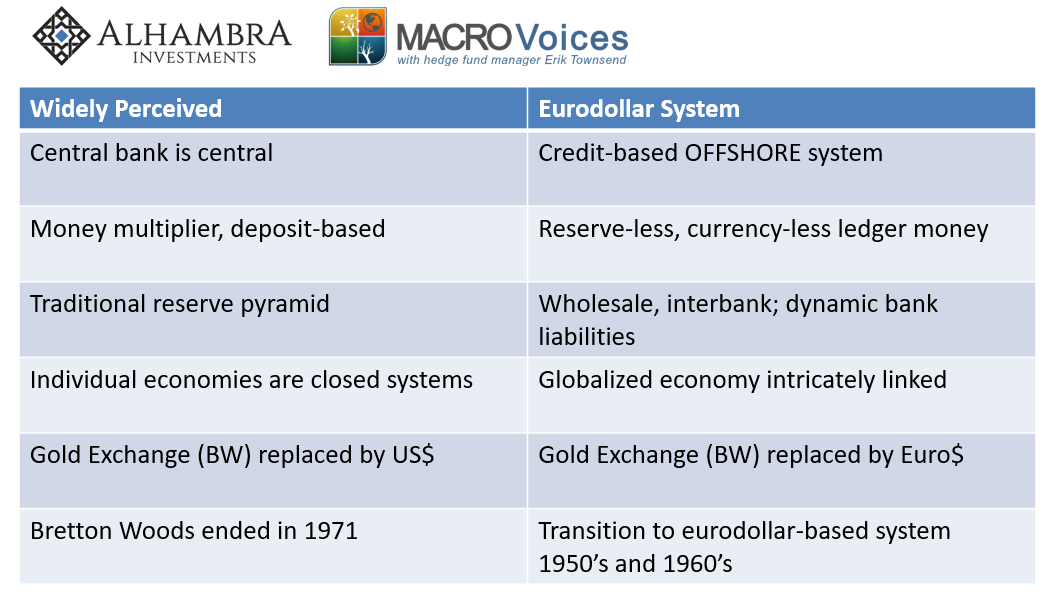

It wasn’t the basis for rational analysis, it was a very public admission of bias and error. We don’t know why inflation ultimately will do what we believe it will, they said, we just believe that it will so you should, too. It sounds ludicrous, but it is actually very much in keeping with standard Economics. The puppet show.

What Mario Draghi said toward the end of January 2018 was:

The strong cyclical momentum, the ongoing reduction of economic slack and increasing capacity utilisation strengthen further our confidence that inflation will converge towards our inflation aim of below, but close to, 2%. At the same time, domestic price pressures remain muted overall and have yet to show convincing signs of a sustained upward trend.

I translated it into plain English:

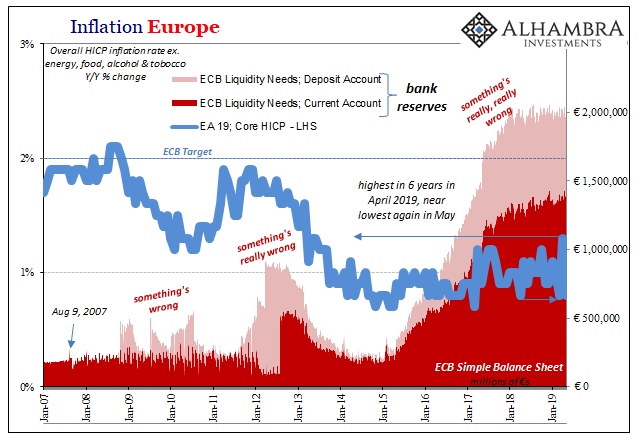

This inflation stuff matters, quite a lot. It matters to begin with for Mario Draghi’s credibility as a proxy for the rest of the central bank’s policies. Without any evidence for his claim, his statement about future inflation can be reduced to: I know that inflation will accelerate because I know that inflation will accelerate. It’s on this basis alone that people follow his pronouncements, though they might not realize it.

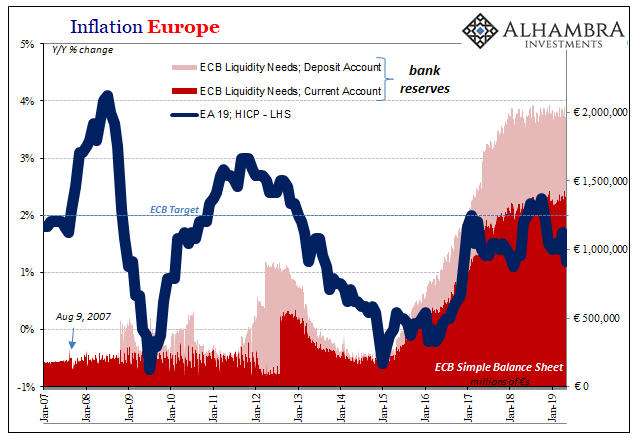

In the post-2008 era, the common response is to argue patience. It’ll all work, you see, just give it more time to show up.

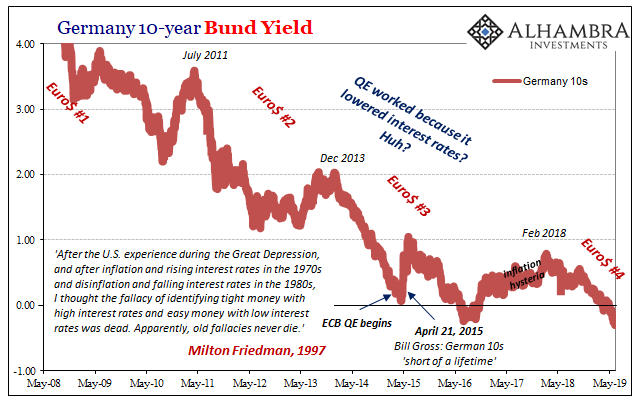

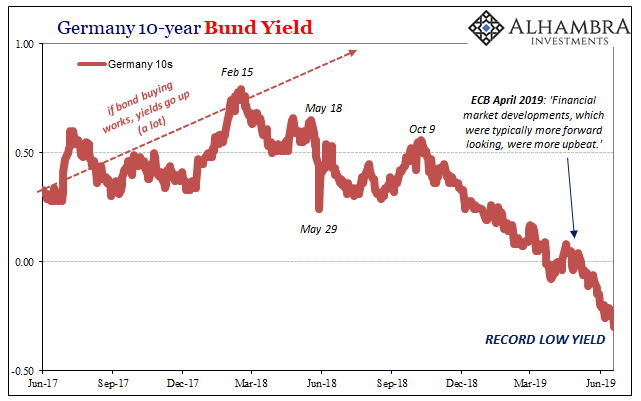

In very broad terms, that’s all the bond market has been arguing. In the European end of the global system, German yields never really moved all that much during what were supposedly the best of times even though Draghi and his ilk couldn’t use the words “strong” and “boom” enough. The real central bank currency couldn’t purchase any “trust us” in bunds.

Bonds were saying maybe your expectations schemes could work on an unlimited timescale. Unfortunately, with this broken global money system you’ll never have that much. Something will almost certainly go wrong before you ever get close to the end. No matter how many bank reserves, liquidity risks were always paramount.

Back at the end of January 2018, global liquidations and for Europe the euro had just topped out. By many data series, their economy had, too. All the signals were in place for a reverse, beginning with what couldn’t have been a boom; else, inflation would’ve showed up long before January 2018.

Over the last year and a half, Mario Draghi has been reluctantly evolving. Kicking and screaming, these central bankers. They’ll deny reality up until the point they finally recognize they have no other option.

Last month, ECB officials were given a very brief window of reprieve. Eurostat reported that in the month of April 2019 the continent had experienced the highest core inflation rate, 1.3%, in six years. The one thing central bankers have wanted more than anything else is a sign, any sign, that tight labor markets are, in fact, tight. If that was the case, they are on track and therefore off the hook.

Headline inflation was nice especially during 2017, but in Europe it was all Brent’s work. Oil prices alone aren’t sufficient. With the overall HICP rate above 2%, there was certainly much less pressure but it still left Draghi with his January 2018 conundrum.

The follow-up inflation report for May, however, dashed all hopes. The core inflation number tumbled back to 0.8%, just 0.1% from matching the record low. The headline number fell, too, without Brent’s help the overall inflation number was just 1.2%. What might’ve been green shoots and transitory factors more and more it really seems entrenched economic (and monetary) negatives.

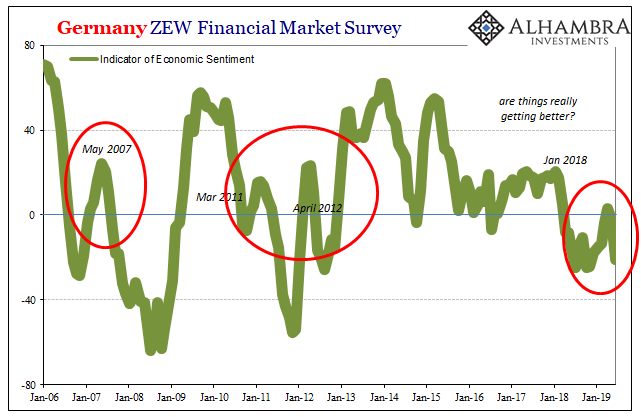

More bad news has followed in forward-looking indicators. Germany’s Zentrum für Europäische Wirtschaftsforschung (ZEW) had reported sentiment estimates seemingly consistent with the transitory/green shoot hopes. After all, it had been the ZEW’s index which had sent the first string of confirmations that Europe’s economy was moving off-track.

The sentiment indicator topped out in January 2018 with the euro, and then plunged starting last April as the euro did, too. Economic accounts particularly in manufacturing particularly in Germany followed into recession territory by the autumn.

In March 2019, however, the index bounced; spring had arrived. By April, the number was positive again. Taken with the core inflation rate, maybe the worst really was over. The ECB even said as much in its official statement given during that month.

As usual, bunds weren’t buying it; actually, they were being hugely bid on the opposite case. Like it or not, the ZEW tends to bounce around even during some of the worst periods. And as Draghi was saying in January 2018, more confirmation was required than one single month of core HICP. Hope, not analysis.

From the standpoint of yield behavior, no surprise then first inflation’s disappointment in May and now the ZEW tumbling to -21.1; just a few points above 2018’s lowest level.

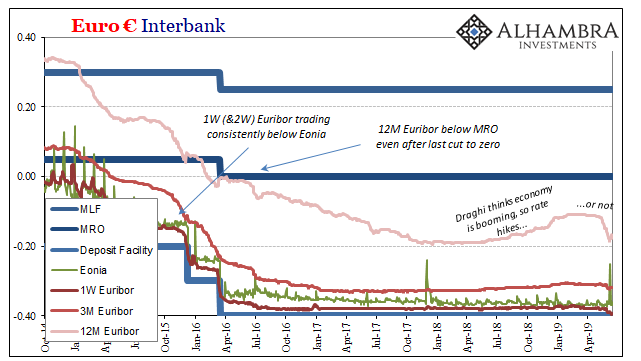

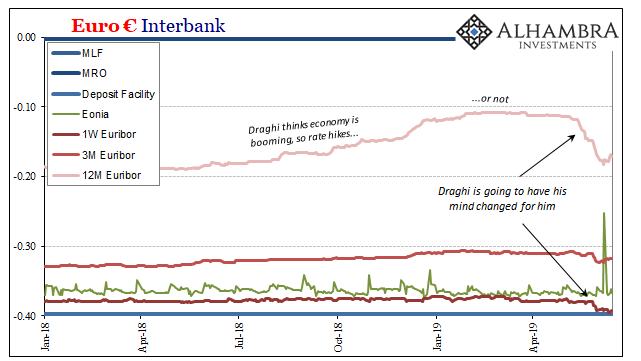

Mario Draghi has had his mind changed for him. Euro money markets are on recession watch already. Today:

Barring an improvement in the economic situation, Mr. Draghi told an audience of economists, “additional stimulus will be required.”

By effectively committing the central bank to action as soon as its next monetary policy meeting, on July 25, Mr. Draghi is ensuring that economic stimulus will linger long after he leaves office.

That last bit is what ultimately matters here. They still call it “stimulus” when how can that be given the way everything has unfolded during Draghi’s quite lengthy tenure? After Trichet’s embarrassment (rate hikes in 2011), Mario’s been on the job “stimulating” more and more since November 2011.

Almost eight years of near constant stimulus is actually evidence it’s not.

It never stops because it never is. Central banks are not central, but central bankers keep thinking their policies are powerful tools for the economy. The bond market, knowing the difference, keeps wondering what happened to rational thinking in Economics. Globally synchronized growth wasn’t a real thing, it was a made-up dream, an emotional plea for success. Depending upon how things turn out on the other side of what’s coming, maybe even a last gasp.

The tepid bounce in 2017 was hyped and overhyped for those reasons alone, which was all that Mario Draghi was telling you…in January 2018.

Stay In Touch