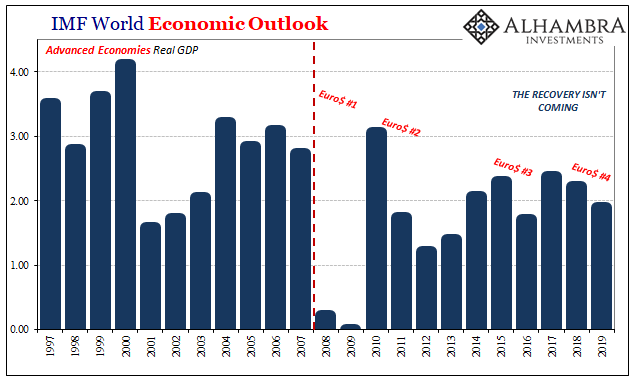

According to IMF, “global growth remains subdued.” Since it was supposed to be roaring by now, this qualifies as a substantial downgrade. Financial positions were staked out on the premise there wouldn’t be one, certainly not a disappointment coming this soon long before the breakout could actually happen.

That’s why there are downside risks in the financial system. Risk-taking wasn’t uniform and ubiquitous in the way it was in, say, the middle 2000’s, but there were plenty willing to put up significant enough sums and take significant enough risks (both Eurobonds) on the premise globally synchronized growth would pay off (significantly).

To the organization’s credit, the IMF acknowledges, “Risks to the forecast are mainly to the downside.” As usual, the reasons for this wrongway tilt are mostly the familiar conventions: trade tensions, “protracted risk aversion” which is something like fears of asset bubbles reversing, lack of growth (disinflation) making debt loads more daunting, and central banks with limited capacities to offset any or all because of R*.

As is standard practice, the latest projections show the global economy coming back next year though not quite at the same rate interpretations of 2017 had promised. Having gone through this all before, the IMF acknowledges how the “projected growth pickup in 2020 is precarious.”

While forecasts for US GDP in 2019 were raised (bring on the second half rebound in the latest figures, they were reduced at the world level (by only 0.1 pts compared to April’s estimates). The biggest contributor to growing weakness is emerging market economies. And the piece of the global economy forcing them lower is global trade (the very place where a disruptive global reserve currency disrupts the most and the most directly).

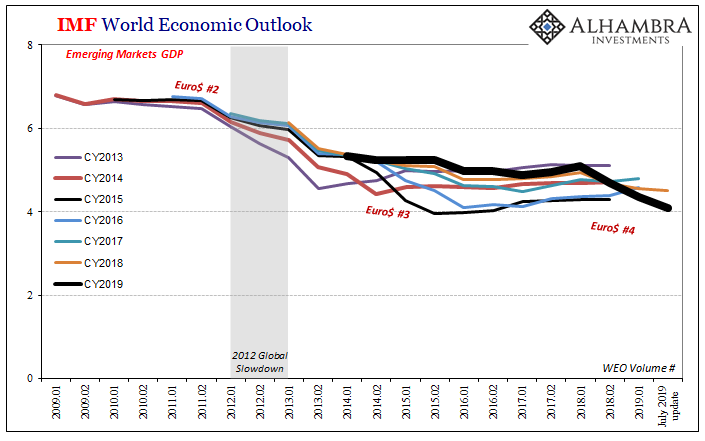

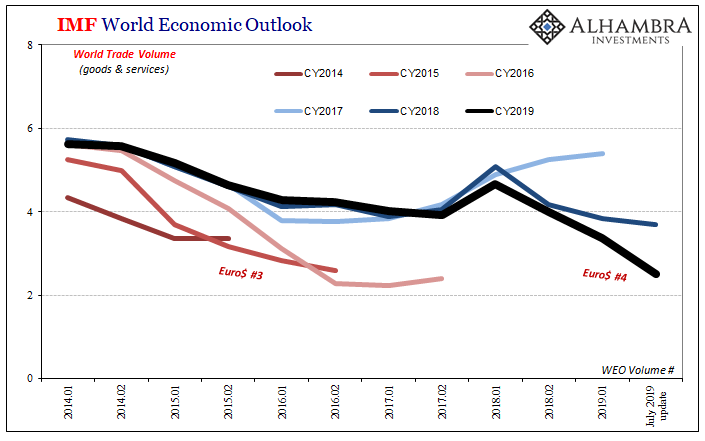

Before Euro$ #3 hit in 2014, the IMF had thought that by 2019 world trade volume would get back up to near 6% growth. This would not have represented full recovery, but at least something resembling the process. The global downturn in 2015-16 corrected the view, thereafter growth projections have been noticeably more reserved.

Not reserved enough, apparently. Outside of 2017 and maybe early 2018, again the downside is re-emerging via Euro$ #4.

World trade volumes are now expected to grow at just a 2.5% rate in 2019, putting this year on the same (low) level as 2015 and 2016. The need for a second half rebound is obvious, else global trade weakens to levels not seen since 2009 – leaving especially EM economies vulnerable.

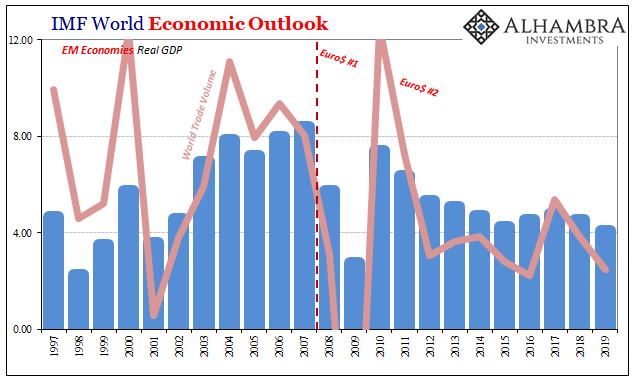

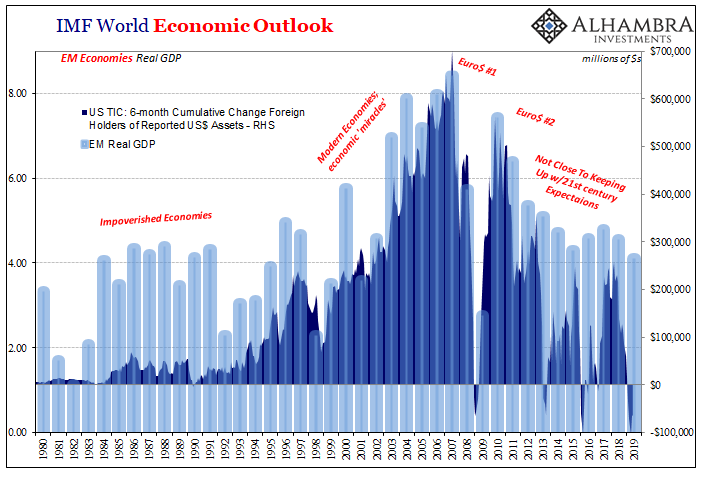

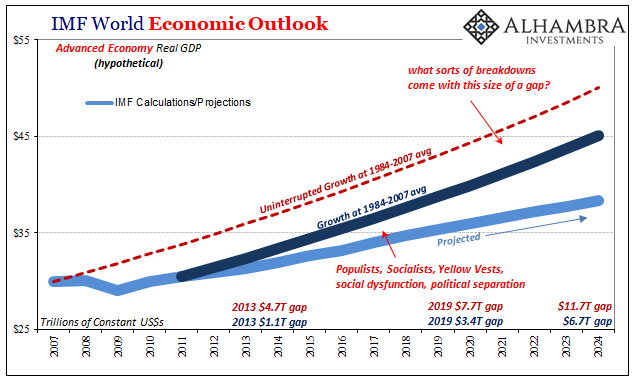

The expansion of trade has been the key catalyst for the developing world. In its absence, going back to Euro$ #2 in 2011, the Asian and Latin American “miracles” have all ceased to function (when growth isn’t growth). The costs, obviously, are more than economic in nature. Political and social dissatisfaction runs high in these places just as it does elsewhere.

That’s what is understated about these downgrades. On the surface, they may not seem like a big deal. The EM economies together managed 4.5% in 2018, so what’s all the fuss if they slow a little to 4.1% as currently projected for 2019? Global dovishness surrounding four tenths of a percent appears a little overdone.

The problem, though, only begins there. It’s not 4.1% this year versus 4.5% last year; the real issue is how first 4.5% should have been 5.5% leading to 6.5% and recovery. These places need meaningful acceleration just to get back to what was “supposed” to have happened (or keep happening).

Interrupting that acceleration, Euro$ #4 proves it isn’t even going to happen. Therefore, 4.1% isn’t just less than 4.5%, that 4.1% calls off the (global) recovery. That’s a pretty big deal especially in places which were just getting used to modern economic standards.

And that’s assuming the world manages a DM second half rebound and no further disruptions. Not even the IMF really believes that will be the case, thus “precarious.” There’s a lot at risk with 4.1% – particularly as it relates to global trade – much more so at risk if 4.1% (inevitably) proves optimistic.

That’s another lesson learned from past experience. Once the downgrades start, they tend to progress much longer than anyone anticipates and go far lower. In the context of 2019, Euro$ #4 began with the world economy much weaker than it was when Euro$ #3 began in 2014 (which was significantly less than when Euro$ #2 started in 2011).

The ratchet effect in full effect. That’s the full and complete meaning of “precarious.”

But that’s everyone else’s problem, right? We can pity those EM’s and promise to make things better by way of trade terms (eventually), hardly something for the Fed to worry about. The US economy and its second half rebound, there’s not really any risk materializing in these figures (especially with the upgrade). Transitory factors all around Europe and the United States.

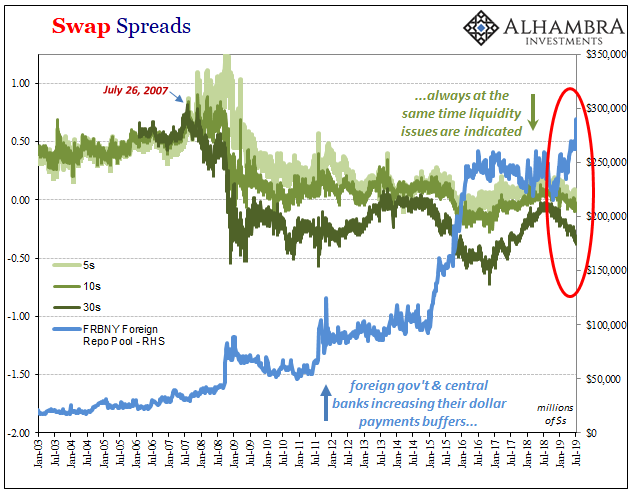

To begin with, DM economies have the same vulnerabilities as the EM’s; and they start off Euro$ #4 in the same shape – falling further and further behind. More than that, though, even central bankers have come to understand, or at least not so flippantly dismiss, the risks if not quite yet why there are so many.

Federal Reserve Chairman Powell recently told a French audience:

The global nature of the financial crisis and the channels through which it spread sharply highlight the interconnectedness of our economic, financial, and policy environments.

In other words, if you see significant deterioration in global trade that then presented EM economies with serious downside risks, what that really means closer to home is how DM economies are far from immune – they are most likely just at the end of the line. The difference is timing; “it” will get to them all in good time.

Unless, of course, DM central bankers can act decisively to head off the negative effects before it reaches their own backyards. That’s the rate-cuts-as-insurance thesis. Jay Powell hears and understands; the “overseas turmoil” that Janet Yellen’s Fed took for granted four years ago will be taken seriously this time around (given the stakes).

The problem with the view is simple; that the Fed can do anything to offset those risks. It will begin to reduce its benchmark policy rates next week, and if monetary policy was potent and the weakness really was due to trade “sentiment” then maybe the stimulus view would prevail. A second half rebound and beyond.

A fourth dollar shortage, however? That’s not something any central bank can manage let alone fix. The IMF downgrades therefore show that its effects have already become serious, the infection has already been spotted and confirmed. At the very least, it’s worthy of serious attention (curves).

And it’s just getting started. Precarious, indeed.

Stay In Touch